The last thing I remember was the sunset. It was a Wednesday evening in 2010 as my friend and I brown-bagged our Four Lokos at the riverbank on Brooklyn’s still-undeveloped Dumbo waterfront. We had been covering the uproar around the alcoholic energy drink for a local publication, and decided to see what the fuss was about for ourselves. I had a few sips of the purple concoction. It tasted of the artificial tang of Smarties with a foreboding bitterness; the sun set over the skyline, and then—nothing. I was told later that we ate pizza, that I called my partner, that I ran… somewhere, and that I hadn’t even finished my can. Oh wait, there was one more memory: This felt weirder, wilder and darker than being drunk. To quote Ralph Wiggum: “I’m in danger!”

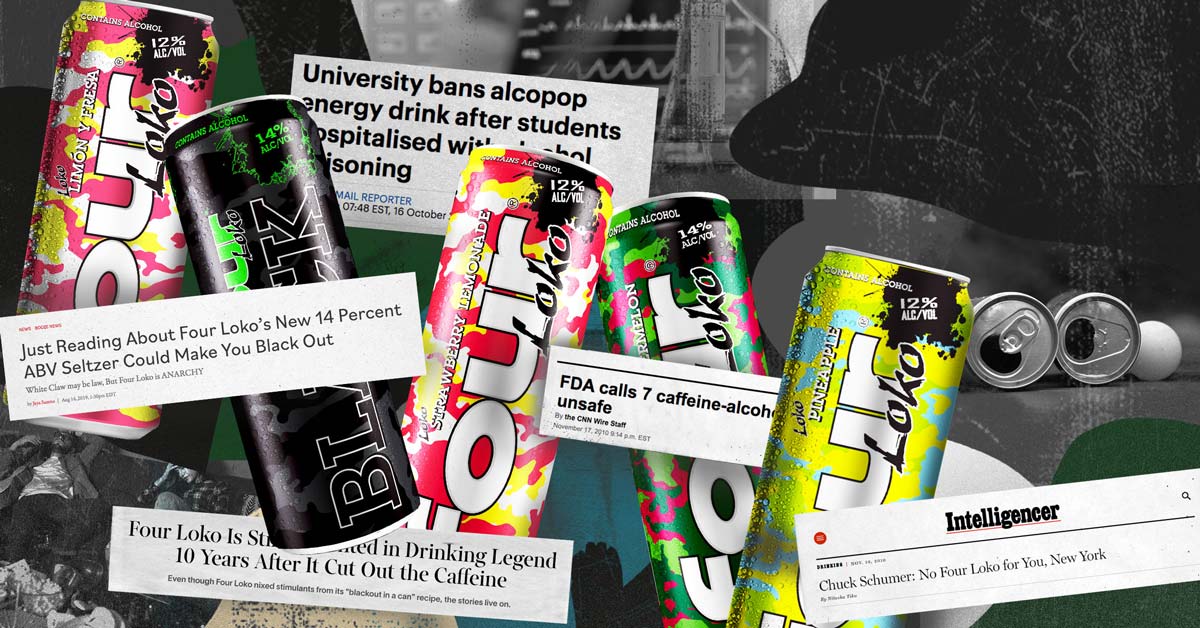

Fifteen years ago, Four Loko as we know it came to life. Parent company Phusion Projects was founded in 2005 by Ohio State University students Chris Hunter, Jaisen Freeman and Jeff Wright, who noticed the ascendant popularity of Red Bull and vodka, and thought to combine the speedball-lite effect into a single product. But it wasn’t until 2008 that they began packaging the drink—a mind-boggling, heart rate–boosting combination of alcohol, sugar, caffeine, guaraná and taurine—in a camo-printed tallboy as bright as a poison frog, and doubled the drink’s alcohol content from 6 percent to 12 percent ABV. When people remember the era of Four Loko, this is what they’re talking about. And though drinks that combined malt liquor and energizing additives existed before Four Loko, nothing captured a particular moment in American culture—one in the midst of a recession, birthing a new wave of internet culture and in which millennials were coming of age—quite like Four Loko, the “blackout in a can.”

@fourlokoNo story like a Loko story♬ original sound – nostalgia central🎶

By the time Four Loko gained national distribution in 2008, its reputation had already caught up with it. That same year, physicians petitioned the FDA to regulate energy drinks, and in 2009 attorneys general from 25 states succeeded in pressuring MillerCoors to remove caffeine from its Four Loko predecessor, Sparks. By 2010, stories were regularly hitting the news about students being hospitalized for high blood pressure and alcohol poisoning after drinking Four Loko, and politicians like Senator Chuck Schumer called for bans. Brooklyn Assemblyman Félix Ortiz, in an attempt to prove to constituents how dangerous it was, drank as much Four Loko as he could in an hour on New York’s NBC station, with a doctor measuring his vital signs. His blood pressure shot up, and eventually he vomited off-screen. He urged New York to ban the beverage. “I was the first legislator around the country to really develop the momentum of banning Four Loko from the small stores and supermarkets,” he tells me. (Ortiz, despite being one of the orchestrators of the political response against Four Loko, did not even realize the drink contained alcohol when he was interviewed for this story.)

This backlash, however, had the effect of making Four Loko all the more enticing to a number of college students and young adults. “It was the 20-year-old version of snap bracelets, where the notoriety and the popularity are kind of inextricably linked to their prohibition,” says cocktail expert and author John deBary. “It was always like, Hey, did you hear about this thing that New York City is banning? Or, Hey, you hear about that kid who died of drinking Four Loko? Let’s drink it.”

Its reckless appeal was only intensified by its relative lack of marketing, which made it feel like a cool, dangerous secret you were let in on. Four Loko hit at a time when social media still mostly consisted of manually uploading photos from your digital camera to Facebook. Day-after albums of everyone getting blitzed, with unmistakable camo cans littered around the dorm, served as their own advertisement.

It was also a time when chefs, whether spurred by the austerity of the recession or just in response to contemporary trends—including the nascent craft cocktail revival, molecular gastronomy and other prevalent “nanny state” legislation around calorie counts and salt content—were conspicuously embracing the lowbrow. “There was this initial secret backlash, and then this very overt backlash to the buttoned-up nature of serious cocktail bars,” says deBary.

In 2010, Robert Sietsema wrote in The Village Voice about the “glamorization of what used to be the substratum of the restaurant industry” happening at the same time. We saw the rise of brash, bro-food culture like Epic Meal Time, which happily endorsed Four Loko; chefs like David Chang and Thomas Keller declared their love for fast food; and restaurateur Eddie Huang specifically embraced the controversial beverage, attempting to throw an all-you-can-drink Four Loko party after the New York State Liquor Authority announced it was considering banning the drink. “Now I gotta figure out how to give people enough Four Loko so they can get their blackout,” he told the Daily News. “People like to black out.”

“Nothing captured a particular moment in American culture—one in the midst of a recession, birthing a new wave of internet culture and in which millennials were coming of age—quite like Four Loko, the ‘blackout in a can.’”

The media attention spurred people who might not otherwise have cared to pick a side in the Four Loko debate, whether it was banning the drink to protect teenagers from hospitalization, or letting consumers make their own choices, even if they were wildly dangerous. “On one hand, this is obviously a product that should be regulated. Really, it’s not a product that needs to exist at all,” says Dave Infante, author of Fingers, a newsletter about American drinking culture. But on the other hand, as many argued at the time, the alcoholic beverage industry had long been finding sneaky ways to market to younger drinkers, whether it was through flashy packaging or candy-like flavors. “Four Loko can be bad or dangerous or ill-advised and also not be wrong about the fact that it’s being unfairly targeted because its peer group, industrially speaking, is more or less doing the same thing,” explains Infante.

Eventually, the Ortizes and SLAs of the world won out. In November 2010, Four Loko announced it would remove the caffeine, guaraná and taurine from its formula, in response to an FDA warning. The change rendered it effectively the same as any other malt beverage on the market. In response, fans stockpiled cans of the original recipe while bloggers attempted to reverse-engineer the drink out of malt liquor, candy and caffeine pills, but mostly, people moved on to the next drinking trend. Four Loko still exists, keeping up with trends by introducing a hard seltzer, flavored shots and Four Loko GOLD, a 14 percent ABV expression, though it has never quite recaptured the zeitgeist.

@fourlokoLife but make it ✨Loko✨♬ i love being dramatic – asstronomyvinyl

Its influence, however, can still be seen today. Four Loko “opened the door to this idea that malt liquor wasn’t stuff that came in 40s exclusively, and didn’t have to be marketed like Olde English,” says Infante. The colorful tallboys of hard seltzer and flavored malt beverages that now fill convenience store fridges—though not nearly as alcoholic, and strictly caffeine-free—sell the same story: This can is made to party.

As luck would have it, on a recent Wednesday I found myself among colleagues, wine glasses in hand, sampling cans of both the OG Four Loko (there was a collector among us) and the current, neutered offering. Tasting notes ranged from “peach ring with an emphasis on the ring” to “what Port Authority tastes like.” But Four Loko was never about the taste. On the subway home, after drinking the equivalent of a third of a can, my brain crackled and buzzed. Even a few more sips could probably have tipped me over the edge, but right there I was alert and giddy and loose. Of course Four Loko became so popular; this felt great.

Highbrow alcohol trends have a way of purposefully evading the fact that we’re dealing with a mind-altering substance. Four Loko, for better or worse, served as a direct, garish reminder of intoxication. It’s a dangerous thing we’re playing with, a fine line between pleasure and harm. But in anything that pushes at that edge, whether it’s Bud Light Lime-a-Ritas at the pool party, Espresso Martinis at the ritzy cocktail bar, or any drink served alongside a mini can of Red Bull, the spirit of Four Loko remains. The taboo has always been the point. Four Loko was just honest about it.