It’s a day that no one could forget. When a dream disappears in a second, and a decade’s work turns to nothing. When a youngster hears from the club of his life: You have no future, not here, not with us. It’s a day that calls for love, support and guidance, but in their moment of need, our young footballers are left to themselves. No wonder they feel rejection, loneliness and despair: Our country’s richest sport has nothing to offer them.

How did it come to this?

The suicides of Joel Darlington in 2019 and Jeremy Wisten in 2020 – young players with so much life ahead of them – sent us a warning.

But they are not alone.

In a recent survey of young players conducted by ITN, almost 90% felt anxious or depressed after their club released them; 72% felt their club had not given them enough support. Hundreds of young players are still suffering today: Talented and powerful athletes, full of ambition, but no less human and fragile than the rest of us. In the darkest moments of their journey with a club, when doubt sets in and the pressure mounts, who is there to help them? Who will listen?

We might reasonably expect that the professional game now acknowledges the gravity of the problem. Resources are certainly not lacking: Over the next three years, the Premier League will earn more than £5bn from UK broadcasters alone. But I’ve yet to see the change in culture or the bold new policy that meets the challenge. I’ve yet to see the PFA perform the most basic duty of a trade union – to protect its members from those who seek to exploit them.

Yes, we have seen some progress. Since the FA adopted the Elite Player Performance Plan a decade ago, clubs have learned to protect their academy players from the worst types of abuse, bullying and exploitation. But the most urgent question – the one revealed by the despair of too many youngsters – is whether clubs are putting young players ‘at the centre’ of their work, as the original plan asked them to. Are they supporting players emotionally and practically, through every phase in their career?

The Performance Plan created the role of a safeguarding officer: Someone within the club who would oversee the mental health and wellbeing of academy players. The intentions were right. But if we look carefully, we see the heart of the problem – something akin to a conflict of interest. In the hothouse of a professional club, where every coach is focused on the next game, every player fighting for their shirt, who can the anxious youngsters turn to? How can they confide in a coaching staff that is always striving for more, when their own mind is clouded by doubt?

In the years after injury brought my own career to an end, I began to look deeper into the sport I had loved and lost. I wanted to see what we could do better. Today, I’m launching a manifesto for change – a Charter for the Protection of Children in Football – so that we restore the dignity, health and wellbeing of our youngsters. And I lay down a challenge to our governing bodies and top clubs: Adopt this plan or do better.

First, let’s puncture a myth. Most academy players earn between £280 and £400 a month – little more than a pound an hour. When they’re not training, they’re cleaning boots, taking care of the laundry. This type of work has a name – exploitation – and a simple solution: The minimum wage. Why would we deny young footballers the basic pay and conditions that apprentices enjoy across the economy?

They work as hard as anyone else. And they leave home earlier than most – often moving to a town they don’t know. Their parents should have a say in where they live and what the accommodation looks like; social and cultural identities should be respected. All young players need to feel safe and secure, especially when they first leave home, and perhaps even more so when their club lets them go. I’ve seen too many ex-players struggle in those first weeks and months of despair: Where they live, and how, really matters.

Young players are neither machines nor assets. Like every human, their body demands respect and care, but too many are suffering from medical negligence. We must stop the painkillers, injections and surgical procedures that are putting young players at risk.

Every intervention should be sanctioned by the parents and an independent doctor. A youngster’s education and emotional development is just as important. Academy players should attend school until the age of 16 at least, receive mindfulness and wellbeing coaching, and be assigned to an independent certified counsellor in mental health; they should never miss lessons for matches or training. All teenagers experience a rollercoaster of emotions, but young athletes undergo unique forms of pressure and stress. Moving from the bubble of the training ground and the changing room – and the banter that is unacceptable in an office or shop – requires extra help.

But the most difficult and urgent problem is aftercare: How we help our young and vulnerable players when they are released by their club. Anyone facing the end of a childhood dream needs time – the time to prepare, seek advice, and start thinking about options. A three-month notice period should be the minimum. Players need professional guidance on what comes next, starting with the opportunities for education, training and employment. Representatives from the PFA should visit clubs regularly; the websites of clubs and governing bodies could point players towards new openings; and, as with universities, players should have public access to data showing how clubs are helping to place their former players.

The UK’s Armed Forces do these things very well. Their aftercare programme was designed by the team of lawyers I’ve worked with. Not unlike young footballers, soldiers devote years of their lives to a world with its own culture and rules, sacrificing the education and social life that millions of other youngsters take for granted. Football’s governing bodies should talk to them.

Economic fairness, physical health, spiritual wellbeing, a sense of security and a path to the future – it may seem like an idealistic manifesto, a vast programme of reform that would be too costly, even for our richest sport. But it’s not. These policies are simple and inexpensive, and we could implement them today. What they require more than anything is the emotional support and practical guidance that youngsters need. No more, no less.

And yet, our governing bodies and professional clubs have scarcely acknowledged the scale and urgency of the problem. For too long, they have banded together as judge, juror, and executioner, even in the face of the most egregious abuses. The Sheldon inquiry into sexual abuse, finally published last year, found only four instances between 1970 and 1995 where clubs had tried (and failed) to respond to reports of abuse. As the inquiry observed, in the absence of any systems or rules, it was left to people’s ‘common sense and experience’ to protect the children. This must be our starting point today, so that we cease to repeat the mistakes of the past. We cannot rely on the good will of some – Crystal Palace have recently adopted some of my ideas – when the safety and health of our youngsters is at stake.

Pressure must now come from the outside, and that moment may have arrived. The government’s plans for a new independent regulator of English football, announced in this year’s Queen’s Speech, present a chance we cannot waste. It is not only the financial sustainability of the sport that is at stake, but its heart and soul.

For too long, our governing bodies ducked the most important questions: What is a club, why does it exist, who does it belong to? And how should it care for the education and wellbeing of its young players?

It is not for the regulator to answer these questions but to empower those actors – players, unions, supporters, local communities, and the clubs who understand their social purpose – who want to embrace a long-term vision of football that is democratic, sustainable and fair.

Last year’s fan-led review showed the appetite for change across the country: A desire to root football’s institutions in the values of dignity, solidarity, and a sense of community. It called for a ‘holistic and comprehensive player welfare system to fully support players exiting the game.’ Only an independent regulator will ensure that clubs take such a duty seriously – and sanction them if they fail.

Let us put an end then to the suffering that has already damaged too many lives. Let us give the new independent regulator the powers that it needs. And let us support our young players at the hardest moment they will ever face, so that the end of a dream becomes the start of a new life.

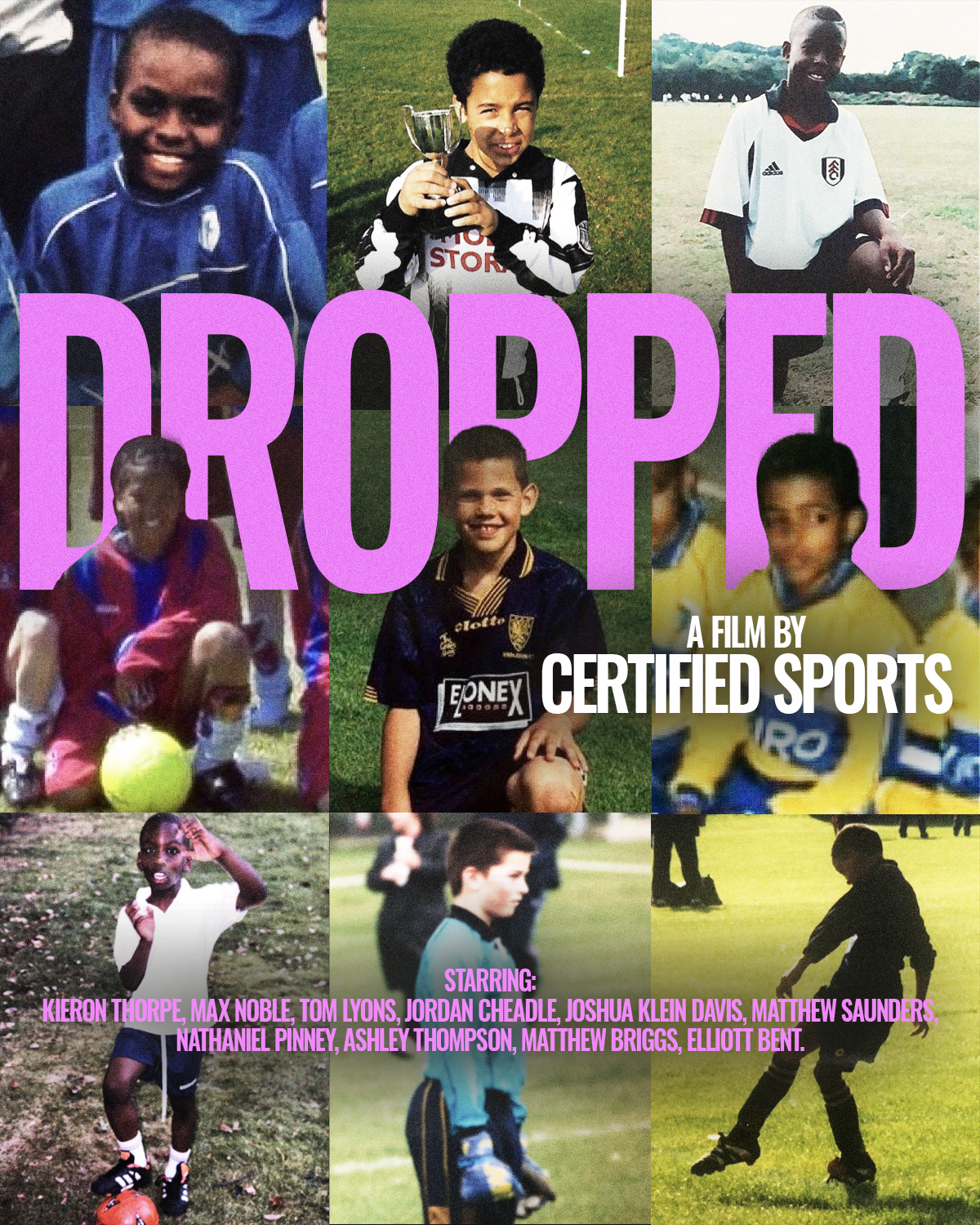

Max Noble is a former academy footballer who played for Fulham FC and Wales. Double knee surgery ended his career early, and his club let him go. In 2018, Max launched Certified Sports – to champion the overlooked and give a voice to the underrated.