AFP

AFPIndia and Canada have expelled their top diplomats amid escalating tensions over the assassination of a Sikh separatist on Canadian soil, marking a new low in a historically cordial relationship.

While past disagreements have strained ties, none have reached this level of open confrontation.

In 1974, India shocked the world by detonating a nuclear device, drawing outrage from Canada, which accused India of extracting plutonium from a Canadian reactor, a gift intended solely for peaceful use.

Relations between the two nations cooled considerably – Canada suspended support to India’s atomic energy programme.

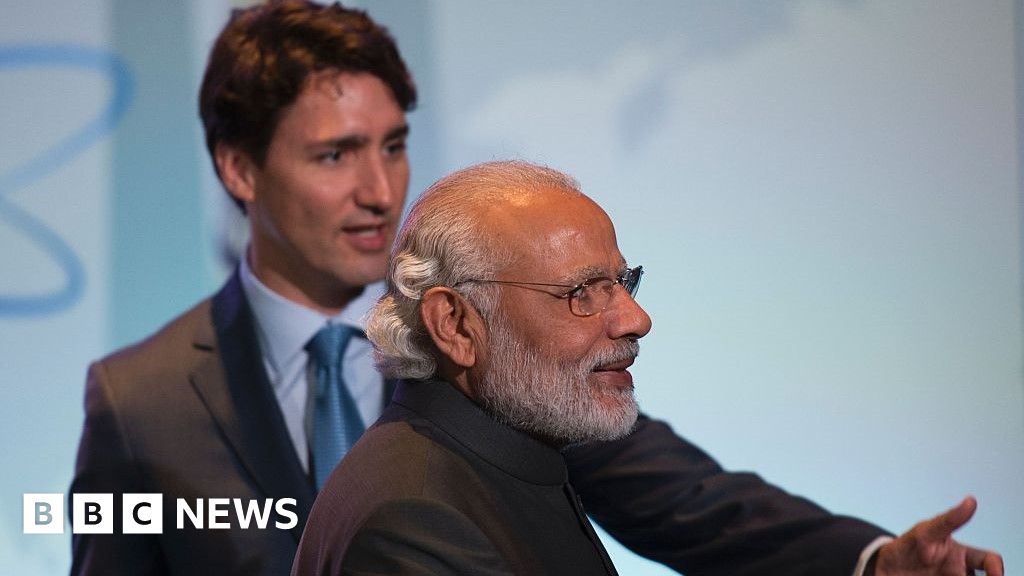

Yet neither expelled their top diplomats like they did on Monday as the row intensified over last year’s assassination of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Canada-based Sikh leader labelled a terrorist by India.

The tit-for-tat expulsions followed PM Justin Trudeau’s claim that Canadian police were investigating allegations of Indian agents’ direct involvement in the June 2023 killing.

Canadian police further accused Indian agents of involvement in “homicides, extortion and violent acts” targeting pro-Khalistan supporters advocating a separate Sikh homeland in India. Delhi rejected the allegations as “preposterous”.

There are some 770,000 Sikhs living in Canada, home to the largest Sikh diaspora outside the Indian state of Punjab. Sikh separatism – rooted in a bloody insurgency in India during the 1980s and early ’90s – continues to strain relations between the two countries. Canada has faced sharp criticism from Delhi for failing to oppose the pro-Khalistan movement within its borders. Canada, says India, is aware of local Khalistani groups and has been monitoring them for years.

Reuters

Reuters“This relationship has been on a downward trajectory for several years, but it’s now hit rock bottom,” Michael Kugelman of the Wilson Center, an American think-tank, told the BBC.

“Publicly laying out extremely serious and detailed allegations, withdrawing ambassadors and top diplomats, releasing diplomatic statements with blistering language. This is uncharted territory, even for this troubled relationship.”

Other analysts agree that this moment signals a historic shift.

“This represents a significant slide in Canada-India relations under the Trudeau government,” added Ryan Touhey, author of Conflicting Visions, Canada and India in the Cold War World.

A history professor at St Jerome’s University in Waterloo, Mr Touhey notes that a key success of former prime minister Stephen Harper’s government was fostering a “prolonged period of rapprochement” between Canada and India, moving past grievances related to Khalistan and nuclear proliferation.

“Instead, a focus was placed on the importance of trade and education ties and people-to-people links given the significant Indian diaspora in Canada. It is also worth noting that the Khalistan issue had seemed to have disappeared since the beginning of the millennium. Now it has suddenly erupted all over again.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCanada’s allegations have come at a time when Trudeau appears to be battling anti-incumbency at home with elections barely a year away. A new poll by Ipsos reveals only 28% overall think Trudeau deserves re-election and only 26% would vote for the Liberals. India’s foreign ministry, in bruising remarks on Monday, ascribed Canada’s allegations to the “political agenda of the Trudeau government that is centred around vote bank politics”.

In 2016, Trudeau told reporters that he had more Sikhs – four – in his cabinet than Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s in India. Sikhs exert considerable influence in Canadian politics, occupying 15 seats in the House of Commons – over 4% – while representing only about 2% of the population. Many of these seats are in key battlegrounds during national elections. In 2020, Trudeau had expressed his concern over protests by farmers in India, drawing sharp criticism by Delhi.

“I think broadly speaking this crisis will give a feeling that this is a prime minister who is seeming to go from one debacle to another. More specifically, within the Indo-Canadian community it may well hurt more than ever,” says Mr Touhey.

He explains that the Indian diaspora in Canada, once predominantly Punjabi and Sikh, has become more diverse, now including a significant number of Hindus and immigrants from southern India and the western state of Gujarat.

“They are proud of India’s economic transformation since the 1990s and will not be sympathetic to Sikh separatism. Historically, the Liberals have been quite politically successful with the Sikh vote, especially in British Columbia.”

However, Mr Touhey doesn’t feel that the crisis with India has to do with vote bank politics.

Instead, he believes this is more about the Canadian government “repeatedly missing signals from Delhi regarding Indian concerns over pro-Khalistani elements in Canada”.

Getty Images

Getty Images“My strong sense is that after decades of pleading with Canadian governments to take Indian concerns over pro-Khalistani elements in Canada, they feel that they’re back to square one – except this time you have a much more different government in Delhi that is willing to act forcefully, right or wrong, to rein in perceived domestic threats,” says Mr Touhey.

Mr Kugelman echoes a similar sentiment.

“There’s a lot at play that explains the rapid deterioration in bilateral ties. This includes a fundamental disconnect: what India views, or projects, as a dangerous threat is seen by Canada as mere activism and dissent protected by free speech. And neither is willing to make concessions,” he says.

All may not be lost. The two countries have a long relationship. Canada hosts one of the largest Indian-origin communities, with 1.3 million residents, or about 4% of its population. India is a priority market for Canada, ranking as its 10th largest trading partner in 2022. India has also been Canada’s top source of international students since 2018.

“On the one hand, the relationship is far more broad-based than ever thanks to the size of the diaspora, the diversity of that diaspora and the increase in bilateral trade, increased student exchanges – albeit this last point has become a problematic issue for the Trudeau government as well,” says Mr Touhey.

“So, I think those people-to-people links will be okay. At the high bilateral level, I don’t think there is much the current Canadian government can do as it pretty much enters the final year with an election to be held at the latest by the autumn of 2025.”

For the moment, though, things look pretty bad, experts say.

“Delhi now levels the same allegations against Canada that it has regularly levelled against Pakistan. It accuses Ottawa of sheltering and sponsoring anti-India terrorists. But of late, the language making these allegations against Canada has been stronger than it has been against Pakistan. And that’s saying something,” says Mr Kugelman.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.