Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBC “One village, two countries” used to be the tagline for Yinjing on China’s south-western edge.

An old tourist sign boasts of a border with Myanmar made of just “bamboo fences, ditches and earth ridges” – a sign of the easy economic relationship Beijing had sought to build with its neighbour.

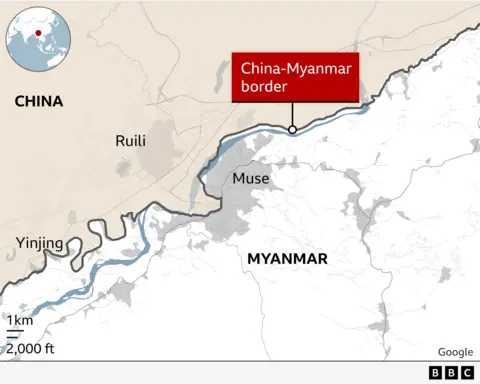

Now the border the BBC visited is marked by a high, metal fence running through the county of Ruili in Yunnan province. Topped by barbed wire and surveillance cameras in some places, it cuts through rice fields and carves up once-adjoined streets.

China’s tough pandemic lockdowns forced the separation initially. But it has since been cemented by the intractable civil war in Myanmar, triggered by a bloody coup in 2021. The military regime is now fighting for control in large swathes of the country, including Shan State along China’s border, where it has suffered some of its biggest losses.

The crisis at its doorstep – a nearly 2,000km (1,240-mile) border – is becoming costly for China, which has invested millions of dollars in Myanmar for a critical trade corridor.

The ambitious plan aims to connect China’s landlocked south-west to the Indian Ocean via Myanmar. But the corridor has become a battleground between Myanmar rebels and the country’s army.

Beijing has sway over both sides but the ceasefire it brokered in January fell apart. It has now turned to military exercises along the border and stern words. Foreign Minister Wang Yi was the latest diplomat to visit Myanmar’s capital Nay Pyi Taw and is thought to have delivered a warning to the country’s ruler Min Aung Hlaing.

Conflict is not new to impoverished Shan State. Myanmar’s biggest state is a major source of the world’s opium and and methamphetamine, and home to ethnic armies long opposed to centralised rule.

But the vibrant economic zones created by Chinese investment managed to thrive – until the civil war.

A loudspeaker now warns people in Ruili not to get too close to the fence – but that doesn’t stop a Chinese tourist from sticking his arm between the bars of a gate to take a selfie.

Two girls in Disney T-shirts shout through the bars – “hey grandpa, hello, look over here!” – as they lick pink scoops of ice cream. The elderly man shuffling barefoot on the other side barely looks up before he turns away.

Refuge in Ruili

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBC“Burmese people live like dogs,” says Li Mianzhen. Her corner stall sells food and drinks from Myanmar – like milk tea – in a small market just steps from the border checkpoint in Ruili city.

Li, who looks to be in her 60s, used to sell Chinese clothes across the border in Muse, a major source of trade with China. But she says almost no-one in her town has enough money any more.

Myanmar’s military junta still controls the town, one of its last remaining holdouts in Shan State. But rebel forces have taken other border crossings and a key trading zone on the road to Muse.

The situation has made people desperate, Li says. She knows of some who have crossed the border to earn as little as 10 yuan – about one pound and not much more than a dollar – so that they can go back to Myanmar and “feed their families”.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCThe war has severely restricted travel in and out of Myanmar, and most accounts now come from those who have fled or have found ways to move across the borders, such as Li.

Unable to get the work passes that would allow them into China, Li’s family is stuck in Mandalay, as rebel forces edge closer to Myanmar’s second-largest city.

“I feel like I am dying from anxiety,” Li says. “This war has brought us so much misfortune. At what point will all of this end?”

Thirty-one-year-old Zin Aung (name changed) is among those who made it out. He works in an industrial park on the outskirts of Ruili, which produces clothes, electronics and vehicle parts that are shipped across the world.

Workers like him are recruited in large numbers from Myanmar and flown here by Chinese government-backed firms eager for cheap labour. Estimates suggest they earn about 2,400 yuan ($450; £340) a month, which is less than their Chinese colleagues.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBC“There is nothing for us to do in Myanmar because of the war,” Zin Aung says. “Everything is expensive. Rice, cooking oil. Intensive fighting is going on everywhere. Everyone has to run.”

His parents are too old to run, so he did. He sends home money whenever he can.

The men live and work on the few square kilometres of the government-run compound in Ruili. Zin Aung says it is a sanctuary, compared with what they left behind: “The situation in Myanmar is not good, so we are taking refuge here.”

He also escaped compulsory conscription, which the Myanmar army has been enforcing to make up for defections and battlefield losses.

As the sky turned scarlet one evening, Zin Aung ran barefoot through the cloying mud onto a monsoon-soaked pitch, ready for a different kind of battle – a fiercely fought game of football.

Burmese, Chinese and the local Yunnan dialect mingled as vocal spectators reacted to every pass, kick and shot. The agony over a missed goal was unmistakable. This is a daily affair in their new, temporary home, a release after a 12-hour shift on the assembly line.

Many of the workers are from Lashio, the largest town in Shan State, and Laukkaing, home to junta-backed crime families – Laukkaing fell to rebel forces in January and Lashio was encircled, in a campaign which has changed the course of the war and China’s stake in it.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCBeijing’s predicament

Both towns lie along China’s prized trade corridor and the Beijing-brokered ceasefire left Lashio in the hands of the junta. But in recent weeks rebel forces have pushed into the town – their biggest victory to date. The military has responded with bombing raids and drone attacks, restricting internet and mobile phone networks.

“The fall of Lashio is one of the most humiliating defeats in the military’s history,” says Richard Horsey, Myanmar adviser to the International Crisis Group.

“The only reason the rebel groups didn’t push into Muse is they likely feared it would upset China,” Mr Horsey says. “Fighting there would have impacted investments China has hoped to restart for months. The regime has lost control of almost all northern Shan state – with the exception of Muse region, which is right next to Ruili.”

Ruili and Muse, both designated as special trade zones, are crucial to the Beijing-funded 1,700km trade route, known as the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor. The route also supports Chinese investments in energy, infrastructure and rare earth mining critical for manufacturing electric vehicles.

But at its heart is a railway line that will connect Kunming – the capital of Yunnan province – to Kyaukphyu, a deep sea port the Chinese are building on Myanmar’s western coast.

The port, along the Bay of Bengal, would give industries in and beyond Ruili access to the Indian Ocean and then global markets. The port is also the starting point for oil and gas pipelines that will transport energy via Myanmar to Yunnan.

But these plans are now in jeopardy.

President Xi Jinping had spent years cultivating ties with his resource-rich neighbour when the country’s elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi was forced from power.

Mr Xi refused to condemn the coup and continued to sell the army weapons. But he also did not recognise Min Aung Hlaing as head of state, nor has he invited him to China.

Three years on, the war has killed thousands and displaced millions, but no end is in sight.

Forced to fight on new fronts, the army has since lost between half and two-thirds of Myanmar to a splintered opposition.

Beijing is at an impasse. It “doesn’t like this situation” and sees Myanmar’s military ruler Min Aung Hlaing as “incompetent”, Mr Horsey says. “They are pushing for elections, not because they necessarily want a return to democratic rule, but more because they think this is a way back.”

Myanmar’s regime suspects Beijing of playing both sides – keeping up the appearance of supporting the junta while continuing to maintain a relationship with ethnic armies in Shan State.

Analysts note that many of the rebel groups are using Chinese weapons. The latest battles are also a resurgence of last year’s campaign launched by three ethnic groups which called themselves the Brotherhood Alliance. It is thought that the alliance would not have made its move without Beijing’s tacit approval.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCIts gains on the battlefield spelled the end for notorious mafia families whose scam centres had trapped thousands of Chinese workers. Long frustrated over the increasing lawlessness along its border, Beijing welcomed their downfall – and the tens of thousands of suspects who were handed over by the rebel forces.

For Beijing the worst-case scenario is the civil war dragging on for years. But it would also fear a collapse of the military regime, which might herald further chaos.

How China will react to either scenario is not yet clear – what is also unclear is what more Beijing can do beyond pressuring both sides to agree to peace talks.

Paused plans

That predicament is evident in Ruili with its miles of shuttered shops. A city that once benefited from its location along the border is now feeling the fallout from its proximity to Myanmar.

Battered by some of China’s strictest lockdowns, businesses here took another hit when cross-border traffic and trade did not revive.

They also rely on labour from the other side, which has stopped, according to several agents who help Burmese workers find jobs. They say China has tightened its restrictions on hiring workers from across the border, and has also sent back hundreds who were said to be working illegally.

Xiqing Wang/BBC

Xiqing Wang/BBCThe owner of a small factory, who did not want to be identified, told the BBC that the deportations meant “his business isn’t going anywhere… and there’s nothing I can change”.

The square next to the checkpoint is full of young workers, including mothers with their babies, waiting in the shade. They lay out their paperwork to make sure they have what they need to secure a job. The successful ones are given a pass which allows them to work for up to a week, or come and go between the two countries, like Li.

“I hope some good people can tell all sides to stop fighting,” Li says. “If there is no-one in the world speaking up for us, it is really tragic.”

She says she is often assured by those around her that fighting won’t break out too close to China. But she is unconvinced: “No-one can predict the future.”

For now, Ruili is a safer option for her and Zin Aung. They understand that their future is in Chinese hands, as do the Chinese.

“Your country is at war,” a Chinese tourist tells a Myanmar jade seller he is haggling with at the market. “You just take what I give you.”