“There is Algeria, follow the light,” the Tunisian official barked at the Black migrants. “If you’re seen here, you’ll be shot.”

François, a 38-year-old Cameroonian, obeyed, jumping off the bed of a pickup truck near the desolate Algerian frontier. A day earlier, the rickety boat attempting to carry him and other hopeful sub-Saharans to Europe — including his wife and 6-year-old stepson — had been interdicted by the Tunisian coast guard in the cobalt blue waters off the coast. Still wet and cold, the group of 30 migrants, including two pregnant women, now walked toward their punishment: the desert.

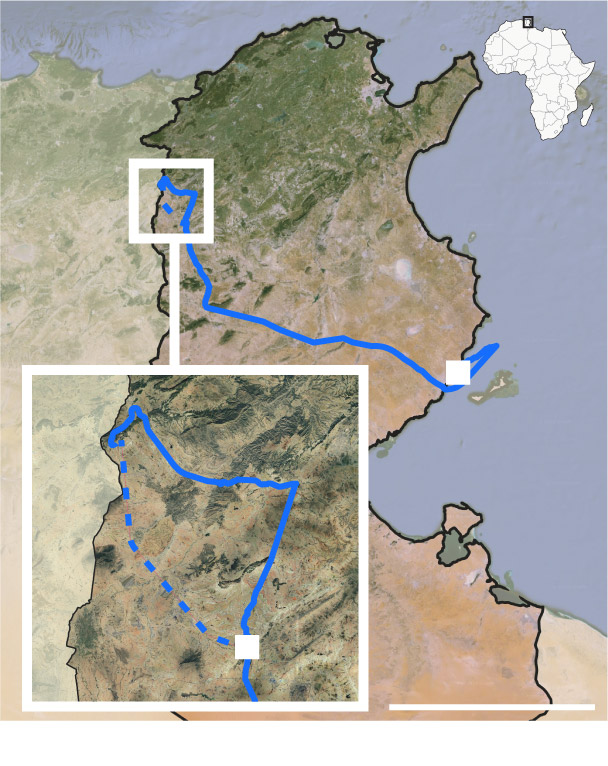

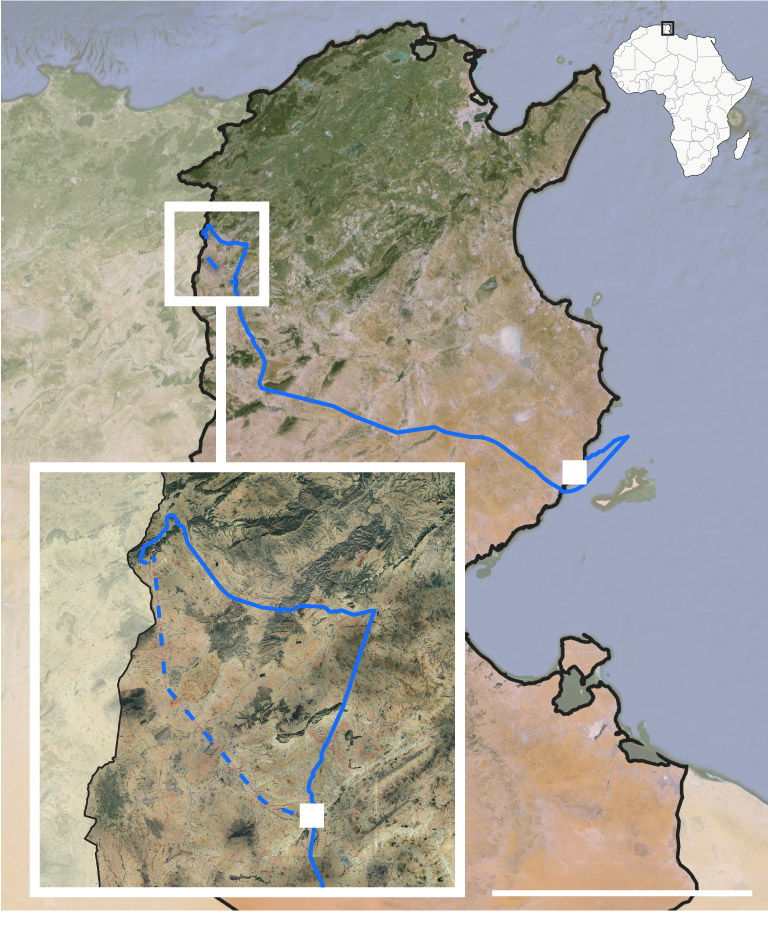

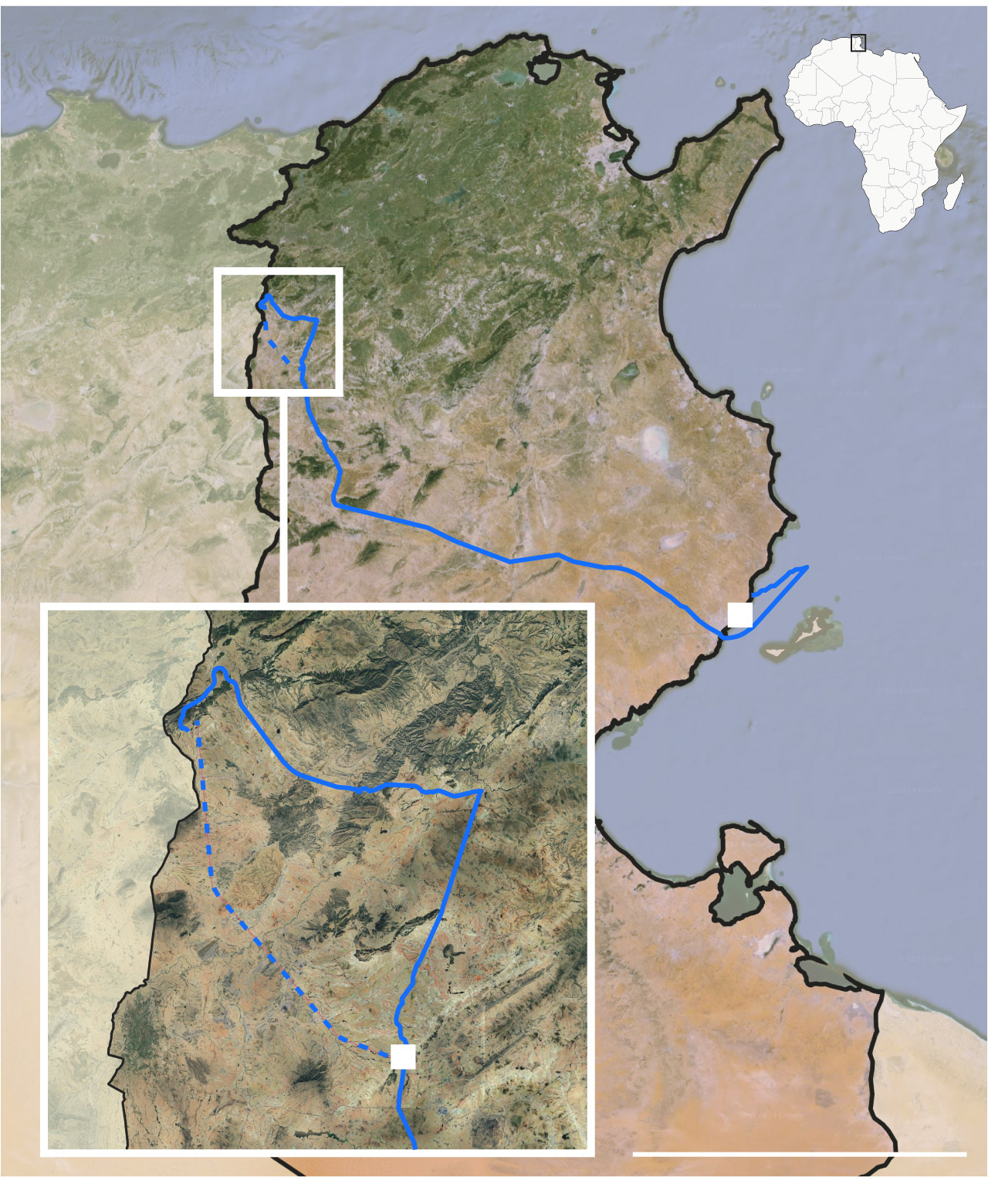

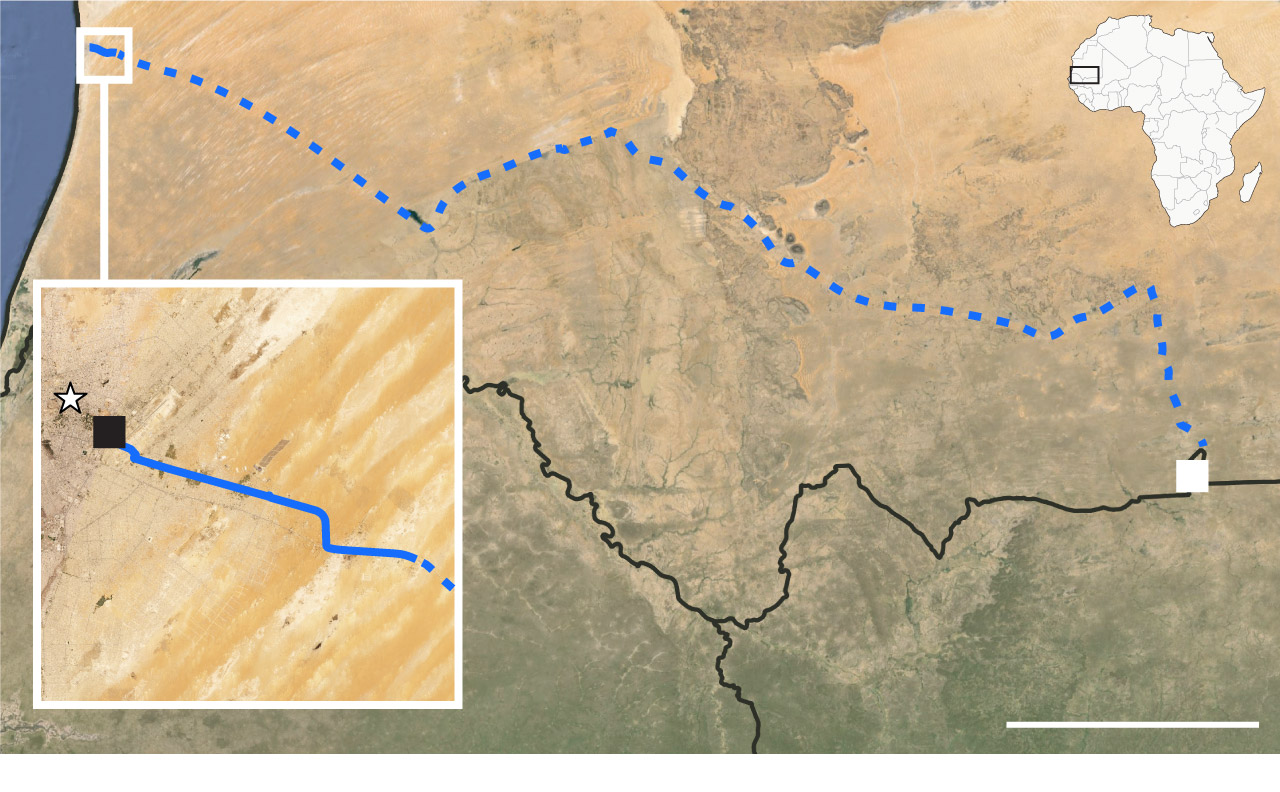

Their ordeal — an odyssey of at least 345 miles from sea to sand, recounted by François and verified by matching GPS tracking on his phone with images and videos he captured during nine days of wandering — illustrates one example of the draconian practices being deployed in at least three North African nations to dissuade sub-Saharan migrants from risky crossings to Europe.

The clandestine operations mainly targeting Black migrants had a silent partner: Europe.

A year-long joint investigation by The Washington Post, Lighthouse Reports and a consortium of international media outlets shows how the European Union and individual European nations are supporting and financing aggressive operations by governments in North Africa to detain tens of thousands of migrants each year and dump them in remote areas, often barren deserts.

- European funds have been used to train personnel and buy equipment for units implicated in desert dumps and human rights abuses, records and interviews show. Migrants have been pushed back into the most inhospitable parts of North Africa, exposing them to abandonment with no food or water, kidnapping, extortion, sale as human chattel, torture, sexual violence and, in the worst instances, death.

- Spanish security forces in Mauritania photographed and reviewed lists of migrants before they were driven to Mali against their will and left to wander for days in an area where violent Islamist groups operate, according to testimony and documents.

- In Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia, vehicles of the same make and model as those provided by European countries to local security forces rounded up Black migrants from streets or transported them from detention centers to remote regions, according to filmed footage, verified images, migrant testimony and interviews with officials.

- European officials held internal discussions on some of the abusive practices since at least 2019, and were flagged to allegations in reports by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and Frontex, the E.U. border agency.

The E.U. provided more than 400 million euros to Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania between 2015 and 2021 under its largest migration fund, the E.U. Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, an initiative to foster local economic growth and stem migration. In addition, the E.U. has funded dozens of other projects that are difficult to quantify and track due to a lack of transparency in the E.U.’s funding system.

To confront a surge of irregular migration last year, Europe moved to deepen its partnerships in North Africa, offering an extra 105 million euros to Tunisia last year and signing a deal in February with Mauritania to provide an additional 210 million euros.

The investigation — focused on Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania, three countries with some of the deepest E.U. partnerships — amounts to the most comprehensive attempt yet to document European knowledge of and involvement with anti-migrant operations in North Africa. It is based on firsthand observations by journalists, analysis of visual evidence, geospatial mapping, internal E.U. documents, and interviews with 50 migrants who were victims of dumps, as well as European and North African officials, and other people familiar with the operations. Like François, many of the migrants agreed to speak on the condition that only their first names be used, out of fear of retribution.

Map of northern Africa, highlighting Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania

In Tunisia, visual evidence and testimony were used to verify 11 dumps — of as many as 90 migrants each — in the desert near the borders with Libya and Algeria, one as recent as this month, as well as one instance in which migrants were handed over at the Libyan border and detained. At least 29 people were reported to have died, with dozens missing after being dumped or expelled from Tunisia on the Libyan border, according to the United Nations Support Mission in Libya and humanitarian organizations.

The E.U., under its own laws as well as international treaties, is obliged to ensure that its funds are spent in ways that respect fundamental human rights. But the European Commission, the bloc’s executive branch, has conceded that human rights assessments are not conducted when funding migrant management projects abroad. Agencies that receive E.U. funds are expected to monitor implementation in partnership with external consultants. But accountability for how equipment and funding are used is often opaque, and senior European officials privately concede that it is “impossible” to regulate all uses.

In comments to European lawmakers in January, Ylva Johansson, the E.U. minister in charge of migration, acknowledged reports of desert dumps in at least one country — Tunisia — and conceded that “I can’t say that this practice has stopped.” But she categorically denied that the bloc was “sponsoring” the mistreatment or deportation of migrants through financial support.

A spokesperson for the European Commission said in a statement that migrant management aid to North African countries is designed to combat human trafficking and “defend the rights” of migrants. The bloc, the statement said, seeks to monitor programs through “spot verification missions,” “monitoring exercises” and external evaluations.

Senior officials in Tunisia, Morocco and Mauritania denied racial profiling and the dumping of migrants in remote areas. They insisted that migrant rights were being respected, though officials in Tunisia and Mauritania have said that some migrants have been returned or deported over their arid borders.

“The fact is European states do not want to be the ones to have dirty hands. They do not want to be considered responsible for the violation of human rights,” said Marie-Laure Basilien-Gainche, a human rights and legal expert at France’s Jean Moulin Lyon 3 university. “So they are subcontracting these violations to third states. But I think, really, according to international law, they are responsible.”

Critics note that the operations are also being carried out against the backdrop of a growing backlash across Europe against irregular migration, an issue that is dominating political debates ahead of key June elections for the European Parliament in which the far right is poised to make record gains.

Analysts and former officials say the objective of the operations in North Africa is clear: deterrence.

“You have to make life difficult for” migrants, said a contractor who worked on projects financed by the E.U. Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. The person spoke on the condition that his name be withheld so as not to jeopardize future contracts. “Complicate their lives. So, if a migrant from Guinea is in [Morocco], and you take him to the Sahara two times, the third time he … asks for a voluntary return home.”

The investigation established through witness testimony, videos taken by reporters and footage verified by The Post that anti-migrant operations often involve raids or random street roundups based on racial profiling — the use of which has been acknowledged in E.U. documents. One internal report on Morocco from Frontex, obtained through a freedom of information request, noted “allegations of racial profiling and excessive use of force by the police and other law enforcement officials against migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees, as well as arbitrary arrests, detentions, and forced relocation from the north to the south, which disproportionately affected migrants from sub-Saharan countries.”

In the Moroccan capital of Rabat, journalists observed three instances over three days in which auxiliary forces that receive E.U. funding rounded up Black migrants in vans. Dozens of videos of similar operations by the same forces were verified as having taken place in Fes, Tangier and Tan-Tan, as well as Laayoune in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara.

“When they see a Black guy, they come,” said Lamine, a 25-year-old from Guinea who, since early 2023, said he has been repeatedly detained and beaten in Rabat, then dumped in the interior by Moroccan forces despite having refugee papers from UNHCR.

In a statement, Morocco’s Interior Ministry described allegations of racial profiling in migrant removals as “baseless” and said migrants were only relocated to protect them from “trafficking networks” and for “increased protection.” It said European “technical support” for migrant management was “minimal compared to the efforts and costs incurred by our country.”

Wandering in the desert

The Sahara has become an increasingly frequent and perilous punishment for migrants daring to cross the sea to Europe.

François, the 38-year-old from Cameroon, had set off four times in overcrowded boats from the Tunisian coast in the hopes of reaching Europe. All four times, he was picked up at sea and returned to land.

Three times, his detention by authorities led to dumps with other migrants at the desolate Algerian border, he said in interviews describing his experiences. His longest ordeal was in September.

The group, including two pregnant women, wandered for nine more days.

In remote border towns, François said they begged for bread and water, sometimes receiving it. After being violently assaulted in one village, he said, they went off-road.

“In the middle of the desert, you look left and right. There’s nothing,” François said. Some began to hallucinate until they navigated to the town of Tajerouine.

Witness accounts and visuals reviewed by The Post place the Tunisian National Guard at the center of desert dump operations. Between 2015 and 2023, the German federal police deployed 449 staff members and spent more than 1 million euros to train nearly 4,000 Tunisian national guards. As the dumps were ongoing in November 2023, a 9 million euro border-management training center opened in Tunisia, funded by Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands.

François’s likely journey by foot, based on visuals The Post geolocated

“I think that Tunisia isn’t responsible for what’s happening,” François said. “The E.U. doesn’t like us. Why is the sub-Saharan man seen as garbage?”

‘Abusive collective expulsions’

Last year, the E.U. recorded 380,227 irregular border arrivals, the third increase in three years and the highest number since the region’s Syrian-led refugee crisis of 2015 to 2016. The political fallout has Europe scrambling to turn North Africa into a cordon to curb illegal entries.

In Tunisia, President Kais Saied recently acknowledged “ongoing coordination” of migration returns with “neighboring countries,” and said Tunisian military forces were intervening to stop irregular migration. “Tunisia will not be a place for them, and Tunisia is working not to be a crossing point for them,” he told his national security council earlier this month.

Migrants’ nationalities range widely depending on their access points into Europe, with the largest route — across the central Mediterranean to Italy — dominated last year by Guineans, Tunisians and Ivorians.

In Tunisia, where Saied has floated a “great replacement theory” that sub-Saharan Africans are trying to supplant Arabs in his country and where Black migrants have been targeted for arrest, more-aggressive tactics have led to ebbing numbers on the central Mediterranean route. That route saw a 59 percent plunge in first-quarter arrivals this year, along with a changing demographic: So far in 2024, no sub-Saharan countries figure in the top nationalities traversing it.

In a statement, the Tunisian Foreign Ministry insisted that it upholds migrants’ rights, only expels them “voluntarily” and only then to countries of origin. The ministry dismissed all allegations in this report made by migrants against its security forces as inflammatory.

The ministry heralded 2,718 operations during the first four months of this year that it said had “saved” and “prevented” 21,545 migrants from crossing the sea to Europe and stopped another 21,462 from “infiltrating Tunisian territory” by land.

European officials have hailed those outcomes.

“This cooperation brings many results. I am thinking, for example, of migration management,” Italy’s hard-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said during an April visit to Tunis, where she praised Saied’s efforts.

In Mauritania, Spanish officials have enabled aggressive tactics, providing vehicles for migrant transport, aiding in sea interceptions, embedding with raids on migrants and human smugglers, and funding new detention centers, according to tenders, interviews with Mauritanian officials and Spanish promotional videos.

Spanish authorities also appear to be complicit in desert dumps.

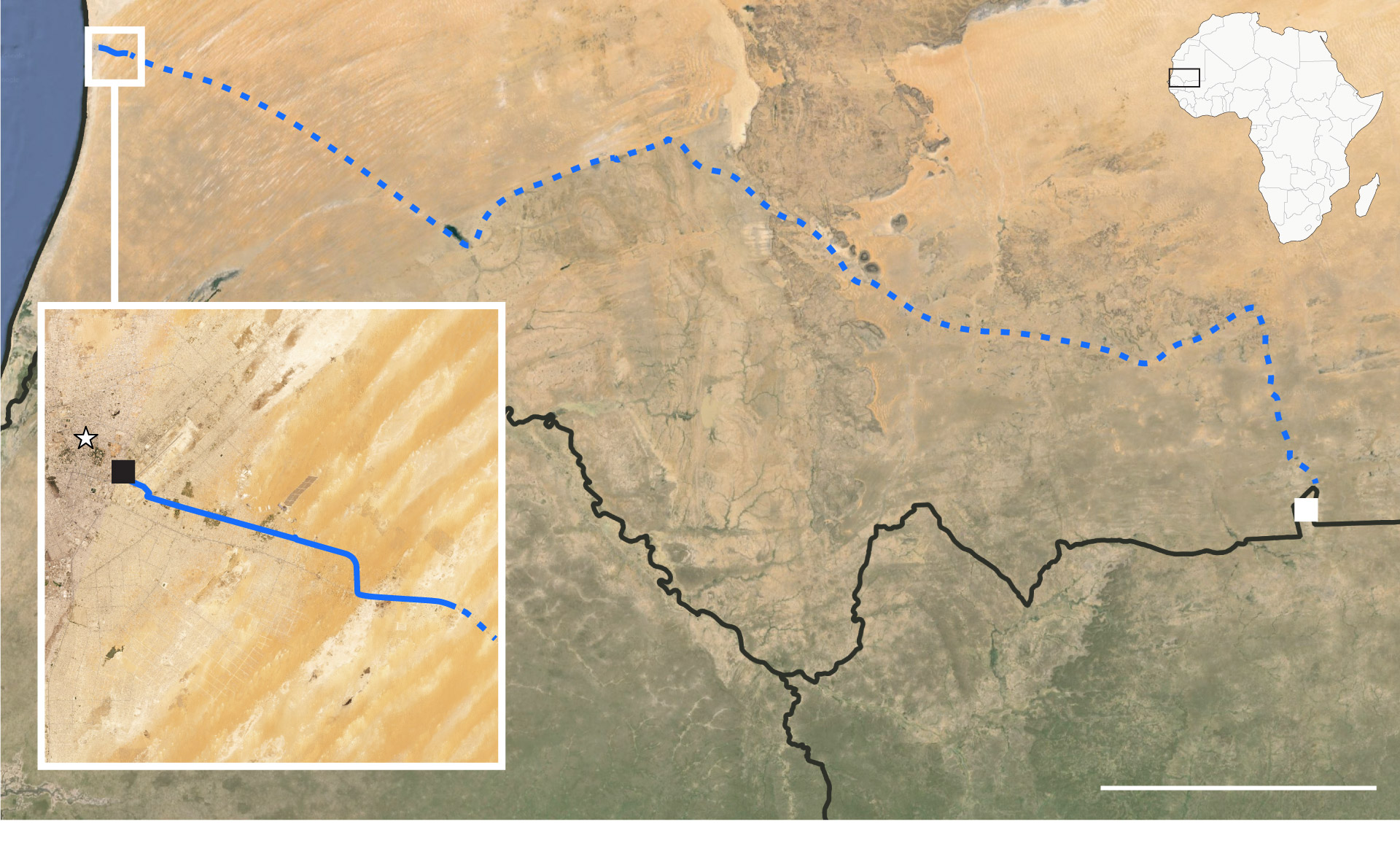

In January, Idiatou, 23, and Bella, 27, two friends from Guinea, were taken to the Ksar migrant detention center — a cluster of heavily guarded and walled buildings — in the Mauritanian capital of Nouakchott after a failed attempt to cross by sea to Spain. The center has become a transit point used by Mauritanian officials before they move migrants to the distant border with war-torn Mali, often without food or water, according to interviews with detainees and aid workers.

A person familiar with Idiatou’s and Bella’s incarceration said that two officials from the Spanish police photographed the women during their detention. According to the person, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution, the officers additionally reviewed a list of prisoners — obtained by the consortium of media outlets — who were later deported to Mali. As with other migrants interviewed for this article, both women said they were denied due process.

In an interview, the women recalled seeing “White” officers who Mauritanian officials told them were Spanish police before being loaded onto a deportation bus. Reporters on the ground observed that bus, a white Toyota Coaster with tinted windows, as it departed Ksar, and followed it for 10 miles along the N3 highway, a road that leads toward Mali.

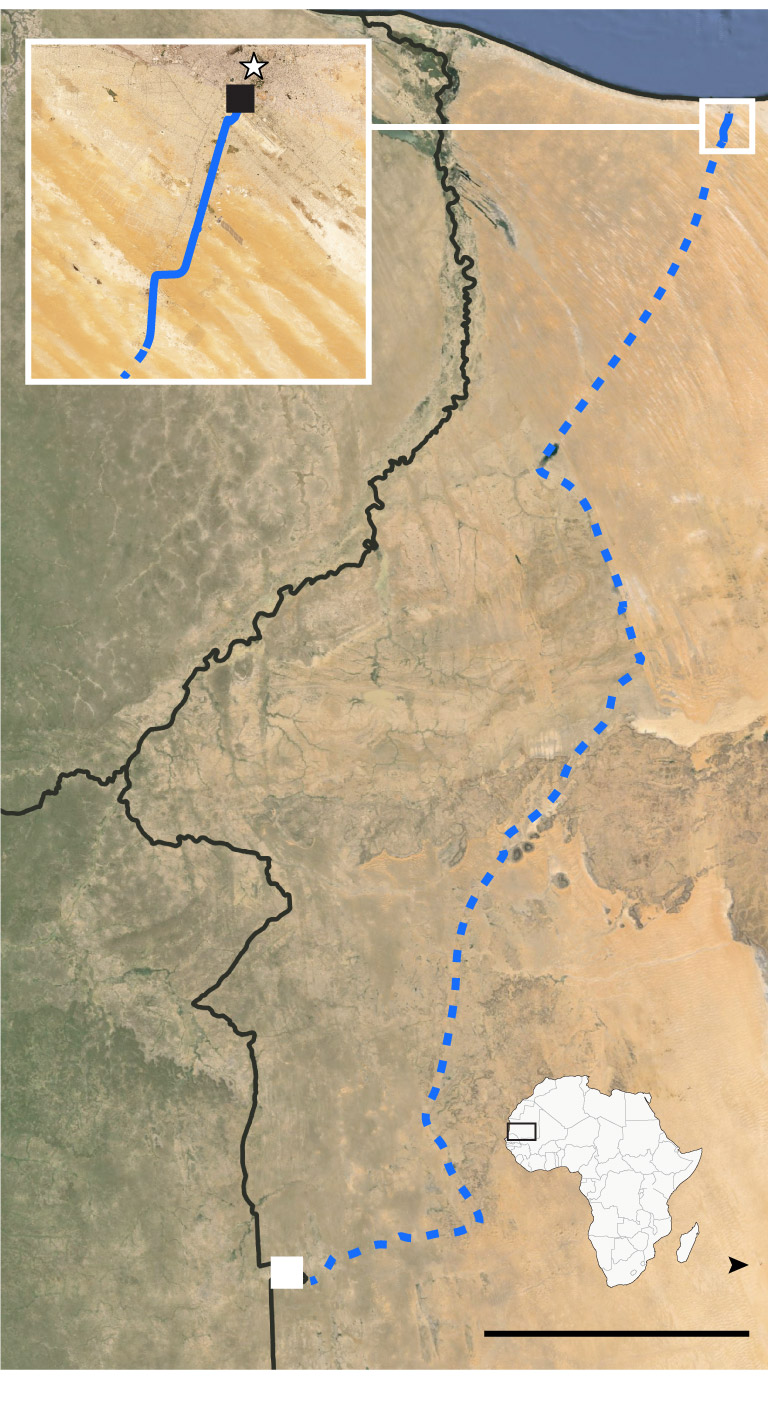

Mauritania map

(Andrei Popoviciu)

Many vehicles used by Mauritanian authorities to detain and deport migrants were bought with Spanish funds, according to a senior European official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive issue. Reporters on the ground filmed Toyota pickup trucks going in and out of detention facilities that were of the same make and model as those tendered by the Spanish development agency FIIAPP and the Spanish Interior Ministry. These include Toyota Hilux pickups supplied by Spain in 2019 with the stated purpose of being used by Mauritanian authorities to combat “illegal migration,” according to tenders.

A report from European Parliament members visiting Mauritania in December described a Spanish coast guard team present at the scene as migrants were returned to shore after attempting a sea crossing. Notes from the report stated that after the migrants were screened, most were “swiftly conducted to the border.” Gilles Lebreton, a member of the European Parliament from the French far right who was on that mission, confirmed that officials had been told about deportations to the borders with Mali and Senegal.

A leaked UNHCR document from 2023 also stated that the agency had interviewed more than 300 people deported from Mauritania to Gogui, Mali. A European Parliament document on negotiations between the E.U. border agency and Mauritania said asylum seekers and migrants in Mauritania faced “abusive collective expulsions to Senegal and Mali” and deportation without due process.

In response to a detailed request for comment, Spain’s Interior Ministry did not confirm or deny knowledge of desert dumps, the use of vehicles purchased with Spanish funds in those operations, or that its officers were in a detention center documenting migrants to be involuntarily deported.

The ministry acknowledged that Spain has deployed a force of about 50 police and civil guard officers in Mauritania to “investigate and dismantle human trafficking mafias.” Those forces, the ministry said, were operating with “full respect” for the “human rights and freedoms” of migrants.

The Spanish development agency FIIAPP denied awareness of dumps, and said Spanish police officers working with its programs in Mauritania “had never witnessed any actions by the Mauritanian police that violate human rights.” Those officers, the agency said, also denied having photographed “any migrants in any center.” It declined to confirm whether vehicles filmed by the consortium in anti-migrant operations were provided by the agency, citing security concerns.

Asked about the Spanish police officers in the detention center, Nani Ould Chrougha, Mauritania’s government spokesman, said in a written statement that a bilateral agreement with Madrid “provides for a number of mutual commitments, including the exchange of information in the fight against illegal immigration while respecting the privacy of individuals and the protection of their personal data.”

He said that migrants who attempt to cross the sea to Europe were subject to deportation, but rejected claims that migrants in Mauritania suffered any mistreatment. Those deported to neighboring countries, he said, were being handed over to “competent authorities” at “official border posts.” He stated that migrants were only being repatriated to their countries of origin.

The two women from Guinea, however, said Mauritanian forces left their group in a desolate, unpopulated part of the frontier with Mali, then “chased” them toward the border “like animals.” They walked in a monochromatic landscape for four days until they reached a Malian village where they eventually arranged a ride on to a relative in Senegal.

The tactic seemed to have its desired effect.

“Had I known all this was going to happen, I would not have tried” to go to Europe, Bella said. “I swear I would not. Because we suffered a lot. … We have nothing.”

Ransom demands

Some detained migrants suffer even worse fates.

Moussa, a 39-year-old migrant from Cameroon, recalled cowering in the desert sand with other Black men on the Libyan frontier in November. Rounded up on the streets of Tunisia’s Sfax hours earlier, the sub-Saharan migrants had been forced into white Nissan trucks emblazoned with the emblem of the national police. At an off-road border guard post, Moussa said he watched as Libyan militiamen handed a briefcase to one of the Tunisian officials.

He guessed at what his new Libyan captors would later confirm: The migrants were being sold.

Moussa’s cousin, a 20-year-old from Cameroon detained with him, confirmed his account. The investigation also reviewed testimony with similar allegations that other migrants provided to Doctors Without Borders and to Refugees in Libya.

In Tunisia, security forces are in possession of at least 143 Nissan Navara pickup trucks provided by Italy and Germany between 2017 and 2023 to “fight human traffickers” or “combat irregular immigration and organized crime,” according to tenders and posts on the embassy Facebook accounts of those countries. Moussa and his cousin said they were forced, along with other migrants, into a vehicle of identical make and model. The Post has verified multiple videos showing the same Nissan vehicles involved in other detentions of migrants in Sfax.

Italy’s Foreign Ministry and prime minister’s office both declined to comment; its Interior Ministry did not respond to a request for comment. Germany’s Interior Ministry, in a statement, acknowledged awareness of limited transfers of “refugees and migrants to the Libyan-Tunisian and Algerian-Tunisian border region in the summer of 2023,” and said that Berlin has “repeatedly made clear to Tunisian partners” that the human rights of migrants “must be respected,” calling the issue “a regular topic of discussion.”

Moussa said that, after his sale to plainclothes militiamen carrying AR-style rifles, he was taken to a small, dirt-floor prison in the Libyan outpost of Al Assah, about 35 miles south of the coastal border crossing at Ra’s Ajdir. There, roughly 500 migrants were packed together under a corrugated roof. Intermediaries told him to provide a phone number for his family in Cameroon, from whom a ransom was demanded. One guard bragged that Moussa and other migrants had been bought for the sum of 20 Tunisian dinars each, a little over $6.

The only toilet in the migrants’ holding pen was a hole in one corner. They were fed once a day, scrumming for noodles served on communal pans. Moussa and other migrants were repeatedly beaten, he said. Speaking via video from a Libyan city, he showed scars on his feet he said were from machete hacks by guards.

To keep the migrants in line, his captors would sometimes randomly fire their weapons. Moussa said he witnessed three migrants die of wounds caused by stray bullets. He was released after his mother — who in a telephone interview from Cameroon confirmed Moussa’s account — spent two months raising the equivalent of $1,000 to pay for his freedom. Unable to bathe during confinement, he said he emerged ridden with scabies and lice. He was dropped off in a coastal Libyan city where he is now working odd jobs for various employers, some of whom, he said, brandish guns after his work is done and then refuse to pay his wages.

“What they’re doing to us is still the system of slavery,” said Moussa, who said he lacks the means to leave Libya. “They have no respect for human beings, no respect for the African man.”

Beatriz Ramalho da Silva, Eman El-Sherbiny, Monica C. Camacho, Tomas Statius, José Bautista, Andrei Popoviciu, Nissim Gasteli, Virgile Demoustier, Jarrett Ley, Junne Alcantara, Laris Karklis and Sarah Hashemi contributed to this report.