The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany published on Tuesday what is thought to be the first comprehensive, verified estimate of the size of this population, where they live and what their needs are. Known as the Claims Conference, it is an organization that secures compensation payments from the German and Austrian governments for Jewish Holocaust survivors.

Six million Jews were murdered by Germany’s Nazi government, in power between 1933 and 1945 — equivalent to two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population before 1933. The Nazis also persecuted and massacred Roma people and other minority groups and political enemies on a smaller scale during this time.

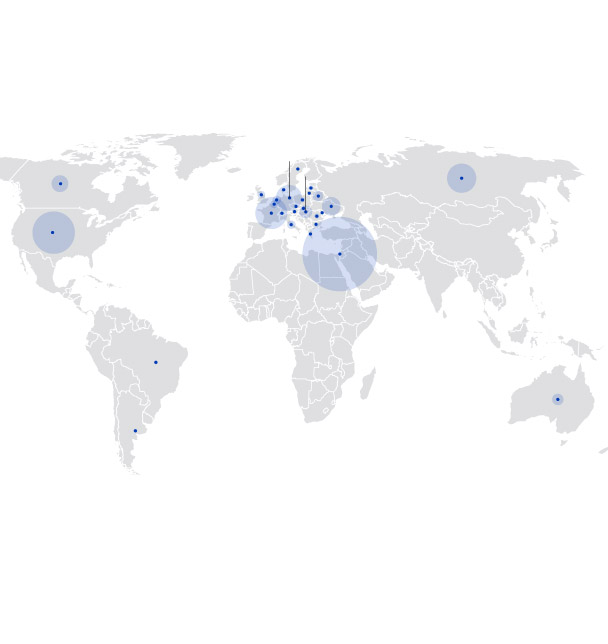

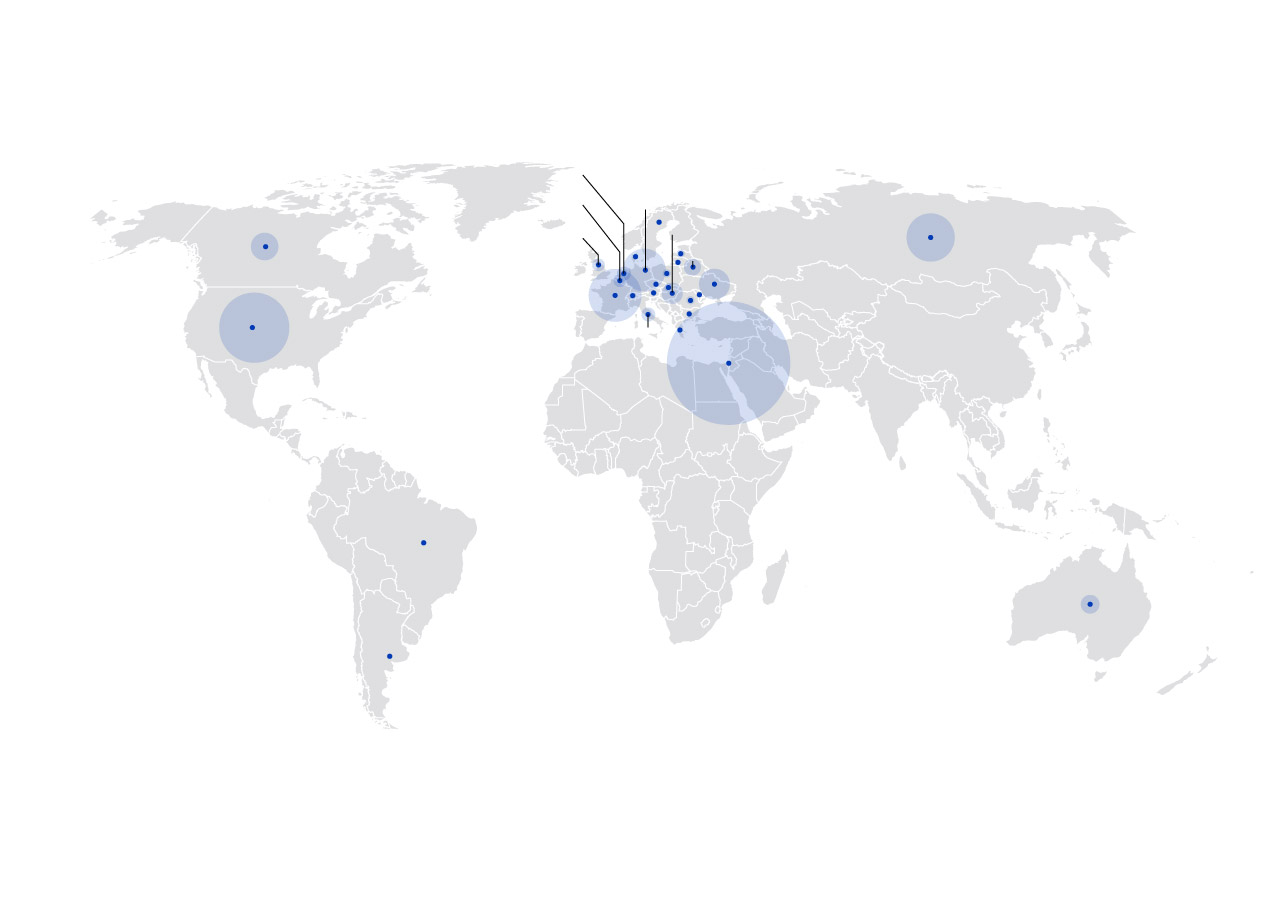

Today, the global Jewish population is estimated to be around 15 million. According to the report by the Claims Conference, survivors alive today are spread out across more than 90 countries. Nearly half live in Israel. The United States, France and Russia host the next largest groups of survivors.

Where in the world do Holocaust survivors live?

Distribution of Holocaust survivors by country

of residence (2023). In percentage.

Note: Map excludes countries that have <0.1% of

Holocaust survivors.

Source: Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against

Germany (Claims Conference)

Where in the world do Holocaust survivors live?

Distribution of Holocaust survivors by country of residence (2023). In percentage.

Note: Map excludes countries that have <0.1% of Holocaust survivors.

Source: Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference)

Most of the survivors alive today were children during the Holocaust: 75 percent were between the ages of 3 and 12 in 1945, when World War II ended. Today, the median age of this group is 86. Over 60 percent are women.

“The data forces us to accept the reality that Holocaust survivors won’t be with us forever,” said Greg Schneider, executive vice president of the Claims Conference, in a news release. “We have already lost most survivors.”

Rüdiger Mahlo, the Claims Conference Representative for Europe, said it’s important not to see just the statistics revealed by the report, but also “the people that are behind it.”

“Those people were doomed to be murdered, all of them,” Mahlo said. “It is our responsibility to care for them until the end of their lives.”

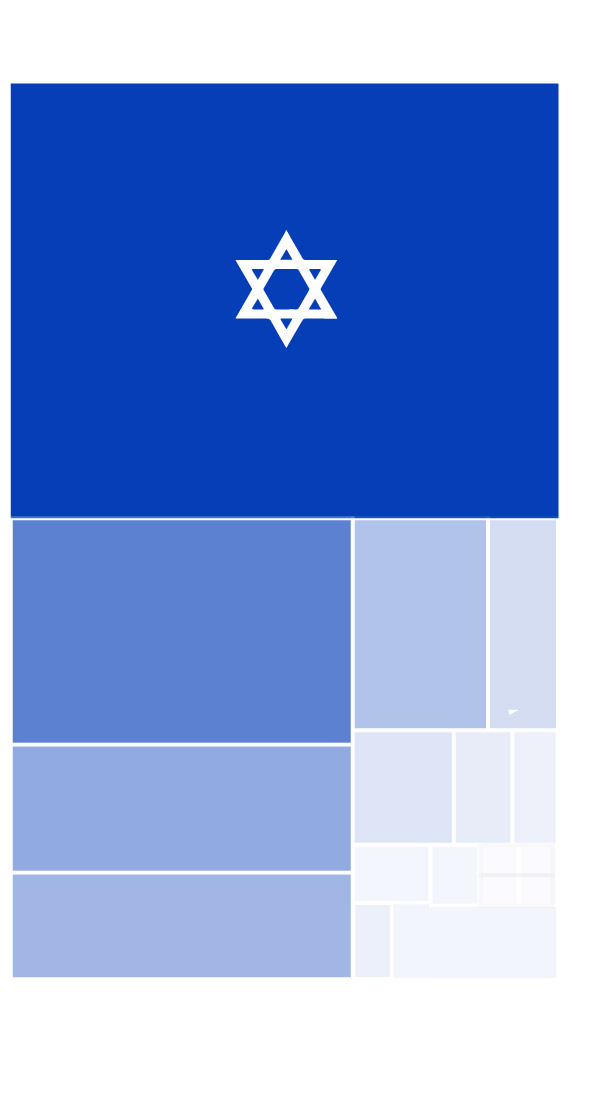

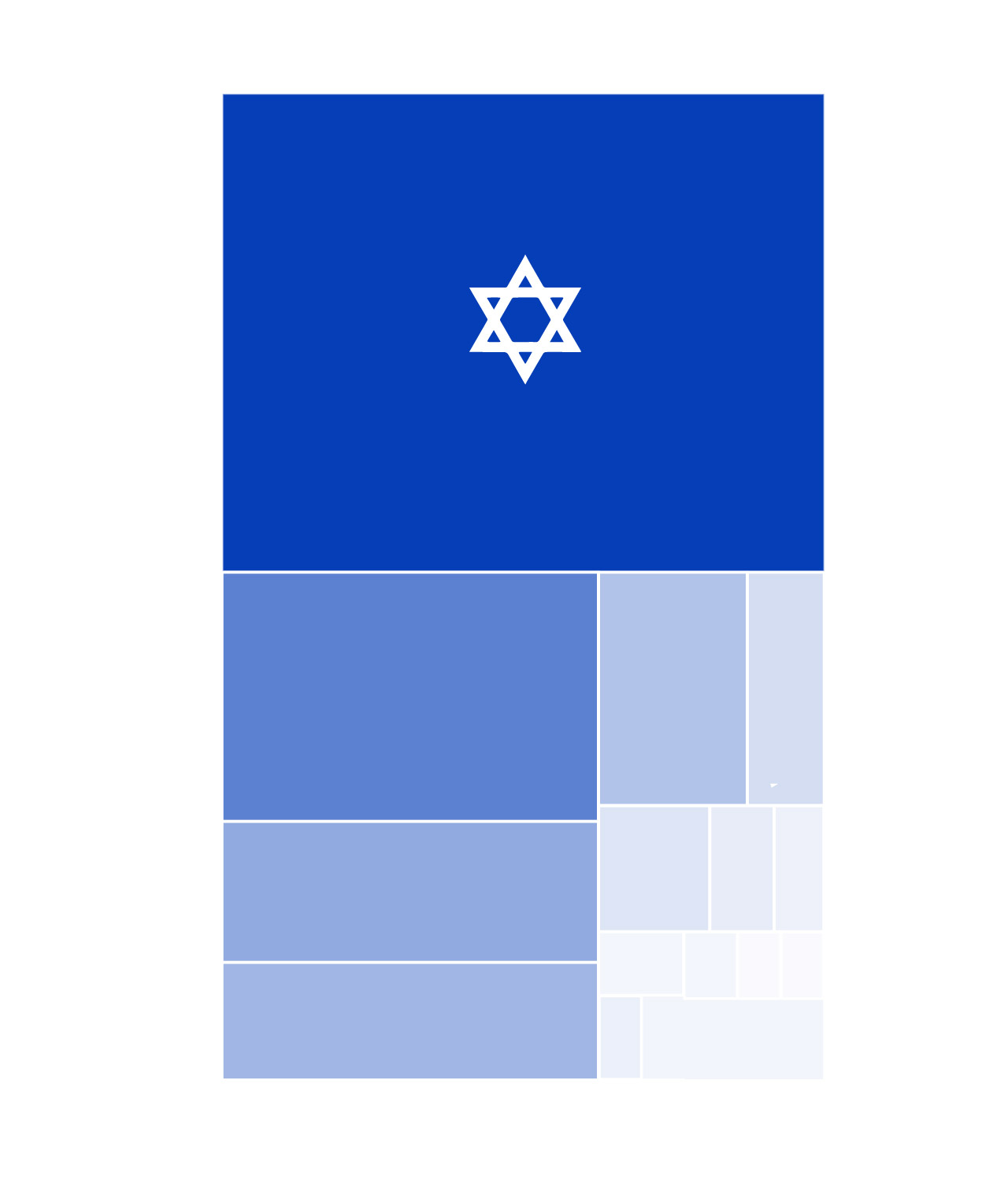

Holocaust survivors by country of residence

Source: Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against

Germany (Claims Conference)

SAMUEL GRANADOS/THE WASHINGTON POST

Holocaust survivors by country of residence

Source: Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference)

SAMUEL GRANADOS/THE WASHINGTON POST

When survivors die, a living piece of history dies with them. Leon Weintraub, 98, one of the living Jewish survivors, said it is more crucial than ever to share and preserve the lessons from that history in the face of Holocaust denialism and rising nationalist sentiment across Europe. Despite the troves of evidence of Nazi crimes, “there are still people who deny that this happened,” he said.

Weintraub was 13 when the Nazis forced him and his family to leave their home in Lodz, Poland, and move into a ghetto, where he learned to work as an electrician. The family was then deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where more than 1 million people were murdered, mostly in gas chambers. Weintraub’s mother and aunt were among them. He still remembers “the smell of burned flesh around-the-clock” and “heavy, black” smoke coming from the chimneys, he said.

Weintraub managed to escape Auschwitz by embedding himself with a group of inmates who were sent to work at a different concentration camp. He was forcibly transferred to two other camps before he was liberated by Allied forces in April 1945. With his body weight down to about 77 pounds, and sick with typhoid fever, Weintraub ended up in a hospital in Germany. Out of 80 members of his family, only 16 survived, he said.

After the war, Weintraub practiced as a gynecologist and obstetrician in Poland and Sweden. Since the 1980s, he has shared his story publicly to raise awareness about the horrors of the Holocaust and help ensure it never happens again. “It begins very innocent, only, ‘I do not like these people,’” he said. “And then it becomes hate” and “ends in the gas chamber,” he said.

Before the publication of its demographic report, the Claims Conference collected data on Holocaust survivors who received regular compensation payments or who were eligible for services administered by organizations that work with the Claims Conference. But it did not have up-to-date information on the thousands of survivors who received one-time payments at some point in the past four decades, including whether they were still alive.

That changed in 2021, when the Claims Conference negotiated with the German government to obtain supplemental payments for some eligible Holocaust survivors. To disburse these yearly payments, which were designed to last through 2027, the organization got in touch with more than 200,000 survivors, according to the report.

The estimate of 245,000 Holocaust survivors alive today does not include survivors who never came forward to receive compensation payments or never contacted the Claims Conference.

Holocaust survivors’ needs are changing as they grow older, Mahlo said. After the Claims Conference was first created in 1951, Mahlo said most survivors who came into contact with the organization wanted to know if they were eligible for any compensation for what happened to them. As they have grown older, “it has evolved into, ‘can I get home care?’”

Nowadays, said Mahlo, they tend to ask more existential questions, such as: “Who will remember when I am not here anymore? Who will remember the fate of my family, of what happened during the Shoah [the Holocaust]? Who will remember … in the way we remember it?”