For most viewing the logo of the Justine Blainey Wellness Centre – named for its resident chiropractor – the ice hockey stick representing the letter J is a reference to Canada’s favourite sport.

It is, of course, but for those who know Dr Blainey – and her remarkable history – better, it is about more than that.

In 1981, Justine Blainey earned a spot on a boys’ team in the Metro Toronto Hockey League (MTHL) but was denied the right to play.

From the age of 12 and throughout her teenage years, she pursued an arduous legal battle of five different court cases, culminating in a hearing with the Supreme Court of Canada in 1987.

Now, more than 30 years on, Blainey, 50, and those closest to her tell their stories in Frozen Out – a three-part podcast series for BBC World Service’s Amazing Sport Stories.

‘I can play, but may I?’

It is spring 1985, and 12-year-old Justine is at home in Toronto, writing a letter.

“I can play, but may I? MTHL tryout time starts today and I’m going to hear the same words again: ‘Yes, you’re good enough. We wish we could take you. But you’re a girl.'”

Justine spells out her reasons for wanting to play with the boys. Girls’ hockey offers just two levels, and only half the number of games a top MTHL boys’ team will play.

She reads the letter one last time with her mum, Caroline, while her brother David practises his ice hockey technique outside with friends. Caroline – a single mum to her two kids – agrees it is ready to send.

This letter will lead to Justine facing off with one of the most powerful organisations in Canadian ice hockey, take her from her mum’s kitchen table to the Supreme Court, and make her a hero to some and villain to others.

‘She can’t go on the ice, we don’t have tampons’

Justine had played ice hockey from the age of seven.

Her family expected her to play what they saw as ‘girls’ sports’ – figure skating and gymnastics – while David played more masculine sports – namely ice hockey.

However, it wasn’t long before Justine started to realise she wanted more. And her mum noticed too.

“Pretty soon her figure skating became pretty boring,” Caroline tells BBC World Service. “She said: ‘They’ve got me on six feet of ice doing figures of nine. I think I’m doing them perfectly and I’ve been doing them for months.’ Yes, she would do what you told her. But not forever – if it’s boring.”

When Caroline asked what she wanted to do instead, Justine answered immediately.

“I wanna play hockey just like Dave.”

At first, Caroline said no – girls don’t play ice hockey. That didn’t go down well with Justine.

“I whined and whined and complained a lot,” she says. “Finally she agreed and found me a girls’ team.”

Justine joined the Leaside Wildcats – a team in the newly founded Ontario Women’s Hockey Association (OWHA).

“I went from figure skating to learning how to skate in hockey skates,” she says. “I could skate fast, but I was horrible with a puck. I didn’t know the rules, so very quickly my brother helped me learn.

“When we did races, I would beat everybody. I was a little bit taller, really good skater from figure skating, but as soon as they gave me the puck, I was dead last. Still to this day, I don’t have the softest hands for stick handling. But what I do have is strength.”

Justine would tag along when David went to practise with his team. Sometimes his coaches would even let her on the ice with them.

She was a natural in defence. She was strong, quick, and easily able to block shots. But when she played with the girls at Leaside, her strength and aggression didn’t work in her favour.

Justine wanted to bodycheck opponents. Bodychecking is, to be blunt, slamming into someone to make sure they lose the puck. It’s common in men’s ice hockey but not allowed in the women’s game.

“Playing hockey with the girls – it was kind of tough,” says Justine. “I hated the fact I could play more aggressively with my brother. When I played girls’ hockey, that led to penalties and people getting mad at you.

“It didn’t take long until I started to say: ‘I want what my brother has.’ By the age of 11, there was full body contact in my brother’s hockey. In girls’ hockey, you weren’t even allowed to touch them. It was a finesse game. And, of course, finesse wasn’t my forte because I didn’t have those stick-handling skills.

“He also got opportunities to have more ice time, more games. The games were even longer. The coaches were more involved.”

The teams David played for also had better uniforms and the best gear. Their practice times were in the afternoon and took place inside.

Justine’s practices with the girls would take place at 5.30am on an outside rink, in freezing cold Canadian winters. She would bundle herself up – sometimes having to borrow her mum’s coat at the last minute – and trying to keep her mind on the game while ignoring the chill.

Something had to give. Justine was passionate, but on a girls’ team she wasn’t allowed to flourish. To her, the solution seemed obvious. She didn’t just want to tag along to David’s practices. She wanted to earn a spot of her own.

David was immediately on board – he’d seen how well she fitted in. Caroline also didn’t take much convincing. Though resistant to Justine playing in the first place, she had seen how good she was.

Convincing everyone else was another matter – and she was subjected to some horrific treatment.

“Some of the tryouts you would get there and they’d say ‘no girls on our ice’ and they wouldn’t even let me try out,” says Justine.

“Sometimes I’d get to their tryout and they’d say ‘OK’ just to appease me, and they’d throw me in a closet that didn’t even have mats for your skates.

“One time, it was so embarrassing. I’m just 11-12 years of age. They came in and said: ‘She can’t go on the ice. We don’t have tampons, we don’t have pads, we don’t have the right way to provide the proper safety in case she gets hurt. She needs proper pads to protect her breasts.’

“I was mortified. I was so young. I didn’t want anybody talking about menstruation. I just wanted to hide.

“But with those tryouts that I was allowed on the ice, my brother was always there to support me. Once I got on the ice, it was so much fun. That’s when I knew that’s where I belonged.”

It still wasn’t enough.

The Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) generally didn’t allow mixed-sex teams in the MTHL. Girls and boys could play together until the age of 12, but only if there were no girls’ teams in the area. For Justine, that wasn’t the case.

We contacted the OHA about this part of Justine’s story, and all the other details you will read later. It didn’t respond.

The rules were holding Justine back, so she decided to rewrite them.

She sent her letter to the Toronto Star – one of the city’s biggest newspapers. It was Caroline, who had initially resisted her daughter’s wishes to play ice hockey, who came up with the idea.

The letter concluded: “Is there an individual or group that can help me? Is there a lawyer willing to donate his or her time to fight this unfairness? I want to be judged on my abilities alone.”

On 5 May 1985, the letter was published. A few days later, the phone rang.

‘I couldn’t see why Justine couldn’t play’

Lois Kalchman reported on minor hockey for the Star and other newspapers for 30 years. She covered everything from major tournaments to changes in fees to kit safety reviews.

She was also always looking for ways to improve it. She was a mother of four children – three boys and one girl. All of her boys played ice hockey.

“If somebody had a problem in hockey, I would try to solve it for them. I wanted the kids to have the best experience they could have,” Kalchman tells BBC World Service.

Kalchman, now in her 80s, remembers Justine and Caroline getting in touch with the newspaper. Her children were about Justine’s age, and she couldn’t see the issue with girls and boys playing together.

“It was an important story because it affected a lot of people,” says Kalchman. “Girls’ hockey was just in the process of growing. Now it’s big and we have international tournaments and all that, but at that time that didn’t exist.

“I was sort of a tomboy as a kid. I liked playing sports with the boys and I couldn’t see why Justine couldn’t.”

Of course, Lois thought it was a good story. But it was more than that. She didn’t just want to write about it – she also wanted to help.

“I was doing a story with the head of a law firm that had this woman on it that was fairly new called Anna Fraser.”

Fraser wasn’t practising that kind of law at the time, but immediately wanted to get involved. Her daughter Dierdre remembers her late mother’s excitement about the case.

“My mother and Justine Blainey – they were a good match,” says Dierdre. “Because my mom wasn’t going to walk away from the human rights case.

“The principle of human rights – of gender, equality, of personhood – mattered to her so passionately. They didn’t see it going anywhere. My mother saw it as a dream case because she understood that it was not about playing a game, not about a kid having some sort of bun fight with a sporting organisation. She saw the case for what it was – a human rights case.”

Justine and Caroline travelled to the law firm’s office in the centre of Toronto.

“I was a bit nervous,” says Justine. “But she was so amazing. She talked to me. She looked me in the eye. She wasn’t talking to my mom. She wasn’t trying to persuade my mom. She was asking me, in simple questions, what I wanted and why.

“I felt listened to. I felt like she cared about what I cared about. And automatically I’ve had this sense of warmth and this sense of trust that started immediately.”

Fraser agreed to represent Justine. Not as part of her day job, but in her spare time. And for free.

“I was very impressed with her backbone and I was impressed with her passion for the situation,” says Caroline.

“We were very, very thankful for a woman who had such passion for Justine’s cause, and not Justine personally – although they got along very well – but for the cause of women being strong and women being where the men had always tread before.”

It placed a lot of pressure on Fraser, who had only been practising law for about five years and was about to take on one of the most powerful organisations in Canadian ice hockey.

In late-night study sessions, she gave herself a crash course on human rights in the province of Ontario. She found that – generally – the Ontario Human Rights Code is clear about sex discrimination: you can’t tell someone they can’t do something because of their sex.

But when she tried to file a complaint with the Ontario Human Rights Commission, she was told she didn’t have a case. While the code stated you couldn’t discriminate based on sex, section 19 point two contained an exception. It basically said if boys and girls were kept separate in sport, that was fine. That wasn’t discrimination.

Of course, the majority of sports teams across the globe – certainly from teenage years onwards – are separated by sex. The main argument for that is the physical differences between men and women, which mean they need to be separated in sport.

But Justine was arguing if a girl was good enough, and if she was chosen for the team, why shouldn’t she be allowed to play? She had proven she was the best person for the spot – and nothing else should matter.

Fraser wanted to get section 19 point two struck down.

But she knew it wouldn’t be easy. It would involve going to the Supreme Court of Ontario. It would involve courtrooms, judges, lengthy legal arguments. And after all that, there was no guarantee of success.

She put it to Justine.

“It was one of those moments where I took the night to think about it and decided that would be – yes – the course of action,” Justine says.

On 11 September 1985, she, Caroline and their lawyer headed to court.

Fraser put forward her arguments.

Number one: Justine was an exceptional hockey player and she wanted more than the girls’ game could offer her.

Number two: she’d been chosen to join a boys’ team because she was good enough. Girls in sport should be judged on merit alone and shouldn’t be held back because of their sex.

Number three: the Canadian Constitution included a section in the Charter of Rights that stated every person in Canada was – in the eyes of the law – equal. So why wasn’t Justine being treated as an equal on the ice?

The case was also backed by a statement of evidence from Abby Hoffman. In 1956, Hoffman had played ice hockey in Toronto, as a nine-year-old, on a boys’ team for about five months. Once it was realised a girl was playing hockey with boys, it caused a media storm in conservative 1950s Canada.

The rules about single-sex teams brought Hoffman’s hockey career to abrupt end so she turned to other sports – most notably athletics. She won eight Canadian championships in the 800m, holding the national record for over a decade, and competed in the Olympics four times.

In 1981, Hoffman became the first woman to be appointed Director General of Sport Canada. Her word meant a lot – and Justine’s case struck a nerve.

“This was, kind of, an updated version of what I had encountered,” says Hoffman.

“When I first started as a serious athlete in track and field as a runner in the early 1960s, the longest distance that women were allowed to run was 800m. Marathons… that was just absolutely, completely unheard of.”

According to Hoffman, the prevailing narrative at the time was that women could not compete in marathons because it would damage their reproductive organs.

It also wasn’t the first time she had offered her support in a case like this. In 1976, she gave evidence at ‘Gail Cummings versus OHA’. The case was basically the same as Justine’s – she wanted to play with the boys. Cummings lost.

In Justine’s case, the OHA had three key arguments of its own.

Number one: girls and boys Justine’s age were too physically different to play ice hockey together. Its lawyer read a quote from the head of Team Canada’s medical staff saying the same thing, and had a number of expert witnesses come up to the stand to support his points.

Number two: Justine could play hockey – she could join a team in the OWHA.

Number three: By keeping girls and boys separate, the OHA was actually helping girls that wanted to play. If mixed-sex teams were introduced, all the talent from the girls’ teams would jump ship. The OWHA backed it on this point.

On 25 September 1985, the judge published his decision. Justine and Caroline had lost.

The judge’s decision was long and full of legal jargon. Put simply, he believed the OHA made a stronger argument when it came to keeping the rules as they were and keeping girls and boys separate in sport. He also dismissed Fraser’s point about the Canadian Constitution as he did not think it technically applied in this case.

For Justine, it was devastating. Her life, not just in ice hockey, was badly affected.

As news about the court case spread, she faced a backlash from the ice hockey community, including on girls’ teams who were convinced she was going to ruin the game for them.

“During the court case, things were tough,” she says. “Some of the things that happened just in grade school… nobody would sit beside me. If you had the desks together, they would push my desk off to the side. So I sat alone.

“Nobody wanted to have a locker beside me. If I was going to the lunch room, I would sit alone. I remember them taking a sanitary pad and putting ketchup on it with my name, and passing it around the classroom, and just being mortified.”

“She had lots of sadness,” says Caroline. “Her friends saying: ‘We can’t play with you any more. You’re crazy.'”

‘I was pushed and bounced off the moving subway car’

Things came to a terrifying head for Justine in 1986.

“I was on my way to see my boyfriend on the subway, one stop,” she says.

At this point, Justine was used to feeling uncomfortable in public places – she was used to people staring, calling her names, even throwing things and spitting at her.

At the top of the stairs to the subway platform, she remembers feeling a push.

“I rolled down the whole flight of stairs,” she says. “It happened really fast. I rolled all the way into the subway that was moving, and kind of just bounced off the moving subway and landed on the platform.

“I jumped right back up, like you would in hockey. Nobody came up and said: ‘Are you OK?’ Nobody came up and said: ‘What happened?’ Nobody said anything.”

Somehow, Justine was not injured. But she was wounded. She was just a teenager. And she felt totally humiliated.

“My first reaction was embarrassment,” she says. “And, again, that I just felt hated, that everybody was looking at me and I didn’t fit in. I was embarrassed. I didn’t want to tell anybody until years later.

“I certainly didn’t tell my mom, or family. I just kept it to myself because I wouldn’t want to worry my mom, and I was mortified that it even happened.”

Justine did have some support, though. Shortly before her court battles began, she had briefly joined – and played for – a boys’ hockey team – the Toronto Olympics. They released a statement.

“We would like everyone to know that we still think of Justine Blainey as a team-mate, and we hope she wins her case this time so that she can play in the play-offs,” it read.

When they said “her case this time”, they were referring to an appeal that Fraser has launched. Even though they lost in the Supreme Court of Ontario, there was still hope the decision could be overturned on appeal.

So, on 22 January 1986 – 11 days after her 13th birthday – Justine headed back to Osgoode Hall, to the Ontario Court of Appeal.

The court reviewed the same evidence – the arguments both lawyers put forward, the statement of evidence from Abby Hoffman, and other important documents from the first court case.

The appeal took only three days, but it was three months before they heard anything.

Then, on 17 April, the appeal court ruled in Justine’s favour.

It agreed to strike down section 19 point two. And the ruling didn’t just apply to ice hockey – it applied to any sport.

“When we won, I was like: ‘Yes! This is amazing! I’m going to get to play!’,” says Justine.

It was not that simple. OHA wanted to appeal against the appeal. To do this, it had to take the case to the highest court in the land, and ask the Supreme Court of Canada.

That was in Ottawa – Canada’s capital city and about 300 miles from Toronto. Justine and Fraser flew out, but Caroline, because of a lack of funds, had to stay at home.

“It was all part of feeling alone,” says Justine. “I went with Anna, but in the courtroom, it was on one side, a huge bunch of people, and then on the other side there was Anna and me.

“I had to put on a fake smile, even though I didn’t know what was going on and pretend like I was being tough and I was all cool, but, honestly, underneath, I felt very isolated and alone.”

Thankfully for Justine, the Supreme Court judges did not take long to make their decision. After just 24 hours, they ruled in her favour.

The court dismissed the OHA’s appeal and agreed that the Ontario Human Rights Code needed to change, to stop girls and boys being separated in sport.

But that was still not quite the end.

By this point, Justine had been accepted into a new boys’ team called the Etobicoke Canucks and was under the impression that she was now officially allowed to play with them in league games. She couldn’t wait. Her first game was going to be at the St Michael’s Arena in central Toronto.

“That was an arena that I loved,” says Justine. “It was arena where I did lots of hockey schools. I was super comfortable in that arena. I’d already put my equipment on and already getting ready to play – and then Lois Kalchman called me out of the dressing room.

As she remembers it, Kalchman pulls her aside to tell her: “Justine, you’re still not allowed to play.”

‘Justine, just one of the boys – finally’

The court of appeal – and, by extension, the Supreme Court – had not said to the OHA: “You must let Justine play on your teams.” In fact, it hadn’t really directed the OHA to do anything.

All it had done was strike down section 19 point two. That did not automatically guarantee Justine a spot in the league. What it did was simply open the door for her to go back to where she started and plead her case again.

With section 19 point two gone, Team Justine were pretty sure they would finally get the win they need. But it meant she has to go back and fight her case. Again.

The OHA offered to make Justine a one-time exception to the rules, which would have allowed her to play – but not any girls in the future, unless they also fought their individual case. She turned that down.

“This is one I did not need to sleep on,” says Justine. “Right away, I said: ‘No way.’

“In my heart, the right thing to do was to make it for everybody. Everybody had the opportunity and I wasn’t willing to say it was just for me.”

Over the next few months came hearing after hearing after hearing. Justine and Caroline, unlike the first time, took the stand and were cross-examined. Their case was heard in the Human Rights Commission, then a Board of Inquiry. Caroline was quoted in the Toronto Star as saying the process was “excruciatingly slow”. A few months turned into a year. And all that time, Justine was left in limbo, unable to play with the boys. She was exhausted.

“Emotionally, I had to deal with a lot of feeling worthy of having friends and feeling worthy of people supporting me,” she says. “Feeling like you were the nail everybody wants to knock down and that you were alone. Like I was always that weirdo.”

It isn’t until a few weeks before her 15th birthday that Justine heard the decision. She had finally done it. After three years and a series of major court cases, she had won.

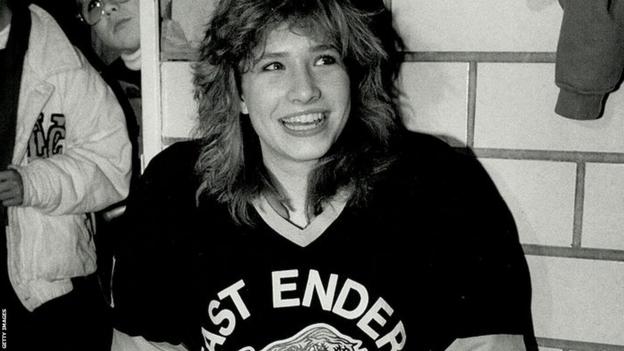

By this point, Justine had just been accepted into a new team – the Eastenders. They had a game just around the corner – against the Toronto Aeros at the Forest Hill Arena.

There was one final twist as Justine’s spot had been given to another player because of the uncertainty. Her brother David, who also played for the Eastenders, quit to free up a spot for his sister.

On 15 January 1988, Justine, her mum and brother arrive at the arena. She walks in and heads straight to a private dressing room. She suits up in the Eastenders gear – a black and yellow jersey with a tiger emblazoned on the front and her number, 55, printed on the back.

Once she and her team-mates are all suited up, they gather in the boys’ dressing room for a pre-game pep talk from their coach.

“The coach did say there’s more fans, there’s more people,” says Justine. “I remember something about ‘just play your game’ kind of thing. You know, the people in the stands don’t matter. It’s only the people on the ice that matter.”

As the team walk onto the ice, there is cheering from the crowd. But she remembers booing, too.

The game starts. At first, she’s a little shaky. She messes up a few passes. She’s feeling the pressure. Comments from the sidelines aren’t making it any easier.

“You would hear: ‘Get her, take her out. She doesn’t belong. Prove she doesn’t belong’,” Justine says. “Even things like: ‘How dare you let her get by you! How dare you let her stop you!'”

After a gruelling match, the final whistle blows. The Eastenders lose 3-1.

“I was excited,” says Caroline. “I was proud that she had stood all those days and months and comments and attacks and insults and held on, made a very important precedent and the fact that she was hitting the ice was a bonus.”

“Team loses, Justine wins” read a headline in The Globe & Mail. “Justine, just one of the boys – finally” the Toronto Star wrote.

For a few weeks afterwards, coverage of Justine’s case continued, with people debating whether it was a leap forward or a step back for hockey. Then, the news cycle moved on.

Justine was left to pick up the pieces and try to get back to a normal life. She continued to play with the boys for a few years. But, as she remembers it, there were still people who didn’t want her out on the ice with the boys – and they made that known.

In her late teens, she decided to go back to playing with girls.

‘Do the right thing, even when it’s tough’

It is easier now for girls in Ontario to play in boys’ teams if they want to. In the 2015-16 season, nearly 100 girls were playing alongside boys in the MTHL.

And despite everything that happened to her, Justine – Dr Blainey – still loves hockey. She plays competitively with a women’s team called the Brampton Cougars. She fits it in around her job as a chiropractor.

Dr Blainey still gets out on the ice with the boys. She plays in a friendly league on a team with her husband Blake and their son.

“Justine’s an amazing player,” says Blake. “She plays the game the way a coach would want a player to play.

“One day, my son and I are on the same team and Justine’s on the other team. And I remember sitting beside my son on the bench and he looks at me. He is like: ‘Man, mom’s mean on the ice.'”

“My kids have heard my story,” says Justine. “I try to really help them, live with integrity. Do the right thing for the right reason, even when it’s tough.

“So I hope that they can, in turn, leave that same message for the generations to come.”