Through a pair of goggles, the operator, call sign Sapsan, piloted the drone across the scarred battlefield in southern Ukraine, gliding the craft toward his target.

Such first-person view, or FPV, drones — fast, highly-maneuverable, and relatively cheap craft flown by an operator wearing a headset receiving the drone’s video feed in real time — are now the predominant attack drone in Ukraine.

They are filling a gap left by a shortage of Western artillery rounds and precision weapons, soldiers said, and their ability to carry heavier explosives has made it the preferred tool for destroying tanks in some units, allowing a pilot to strike weak points like engines and tracks with rapier precision.

Sapsan means peregrine falcon, and as his synthetic raptor approached its target, a navigator huddled next to him. “You can carefully fly around,” the navigator said. “See if there is a way in.”

Then, a breakthrough: a hole leading inside the dugout, perhaps three feet tall and three feet wide. Sapsan drew nearer. Indicators in his headset flashed low battery warnings.

“The wind,” Sapsan said, cursing. “Come on, work for us.”

The war in Ukraine is the world’s first full-scale drone conflict, and FPV drones, first used in substantial numbers earlier this year, are bringing it to a new level. Though more difficult to fly than other drones that drop munitions, Russian and Ukrainian soldiers are mobilizing fleets of them.

FPV cameras create bleak images that are destined to go viral: The last oblivious seconds of soldiers’ lives, war machines set ablaze and trick shots plunging through open windows. It is captured on low-fidelity video reminiscent of VHS — an advantage, soldiers say, because the analog signal resists electronic jamming better than digital feeds.

Perhaps most important for Ukraine’s asymmetric fight against Russia — a far bigger, better-armed enemy — FPV drones are bargain-bin projectiles. Fashioned by hand from a few hundred bucks of material, they can annihilate million-dollar equipment.

“It’s a revolution in terms of placing this precision guided capacity in the hands of regular people for a tiny fraction of the cost of the destroyed target,” said Samuel Bendett, a drone expert at the Center for Naval Analyses, a policy institute based in Arlington, Va. “We’re seeing FPV drones strike a very precise spot, which before was really the domain of very expensive, high precision guided weapons. And now it’s a $400 drone piloted by a teenager.”

Bendett likened the use of FPV drones to the iconic Star Wars scene, when Luke Skywalker fires a proton torpedo into an exhaust port to destroy the Death Star. “This is what we’re actually seeing happen right now,” he said.

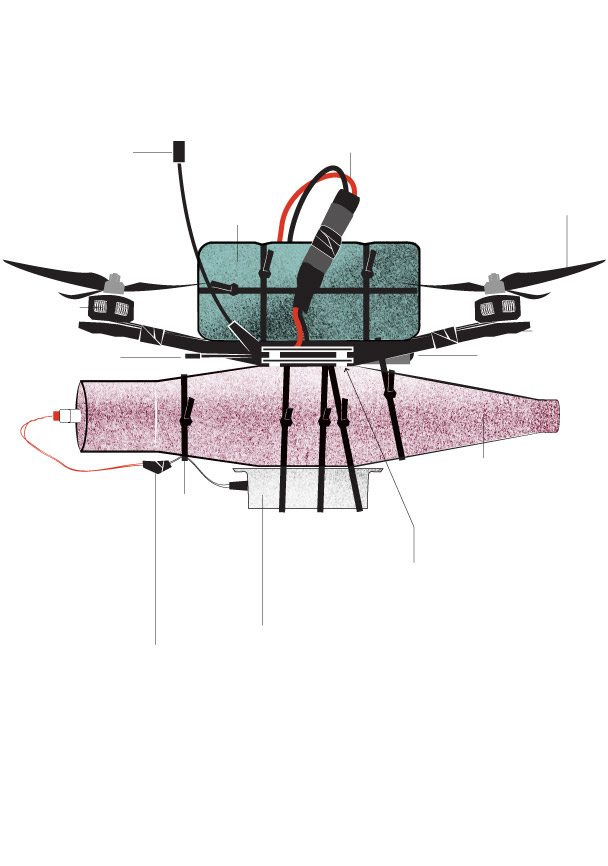

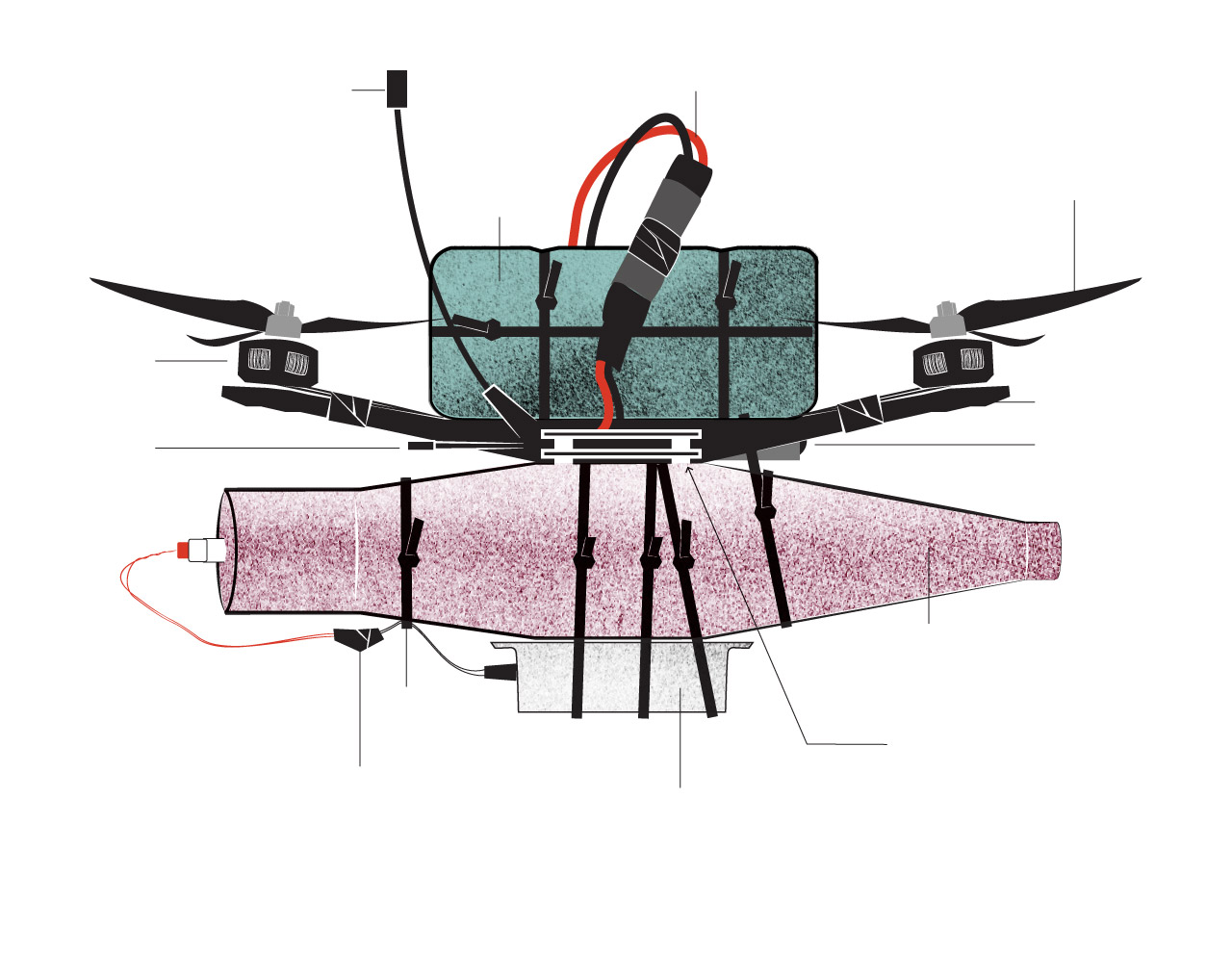

FPV drones are arguably the most DIY weapon in Ukraine’s crowdfunded war. Brimming with Chinese-made components, they are assembled by volunteers or by units themselves. The drones are built for obliteration, and look it. Power cables flare from their top. Explosives are secured with plastic zip ties.

A pilot typically works with a navigator, and a second team flying a surveillance drone to capture the larger view. FPV drones often miss more often than they hit, crews said, with failures resulting from electronic jamming or batteries dying. The drones have a roughly nine-mile range, depending on payload size.

Basic components of a hand-built

FPV war drone

RPG warhead or

other explosive

Power distribution

and flight controller

boards

3D printed

initiator casing

(triggers

explosion)

Source: Ukrainian military

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Basic components of a hand-built FPV war drone

RPG warhead or

other explosive

Power distribution

and flight controller

boards

3D printed

initiator casing

(triggers explosion)

Source: Ukrainian military

SAMUEL GRANADOS / THE WASHINGTON POST

Drones designed to crash into targets are known as one-way, or self-detonating, drones. The United States has provided Ukraine with similar but expensive models in relatively small numbers, and these are not new to conflict.

When the war shifted predominantly to an artillery fight last year, both Ukraine and Russia began favoring smaller tactical drones. Troops fixed grenades and smaller explosives to quadcopters, like the popular DJI Mavic, and rigged them, like tiny bombers, to drop directly over targets.

The concept worked for a time but was unsustainable, soldiers said. Off-the-shelf tactical models can cost more than $2,000. Analysts estimate Ukraine loses thousands of drones a month.

Those drones also cannot carry much. Mavics can haul about a pound of explosives, said Senior Lt. Yuri Filatov, the drone systems chief commander of the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade. That is roughly a hand grenade — enough to kill a soldier but not destroy vehicles.

Filatov’s brigade has found that FPV drones could carry the warhead of a rocket-propelled grenade, a readily available antitank weapon. Their introduction, he said, has even lessened the need for more expensive weapons like the U.S.-provided Javelin.

“FPV drones have become the main antitank weapon,” Filatov said, including against T-90s, which are among Russia’s most modern tanks. In one day alone, they destroyed four tanks, he said, while soldiers kept at a safe distance. “As we use more drones,” Filatov said, “we are losing fewer people.”

Prepping for drone warfare

Before dawn on a recent morning in the Zaporizhzhia region, soldiers of the 47th drone strike company chain-smoked cigarettes and chugged energy drinks as they loaded boxes of drone components and antennas into a pickup truck.

The company’s chief sergeant, a bearded former DJ with the call sign Legion, got behind the wheel and sped toward the front. With techno music from Legion’s past life as a soundtrack, the truck skimmed by the torched shells of armored vehicles. The turret of a U.S.-supplied Bradley, destroyed by a mine, lay upside down in scattered trash.

Washington Post journalists accompanied the drone team — Legion, pilot Sapsan, and navigator Actor — on a day-long mission near the liberated village of Robotyne. The objective: sow chaos on Russian lines as their comrades fought to retake ground, trench by trench. In keeping with military rules, the soldiers are being identified only by their call signs.

Heavy Russian glide bombs shook the ground in the distance as the team put up antennas and readied a Starlink satellite internet terminal. Enemy detritus on the floor — fragments of Russian uniforms and discarded rations — showed enemy soldiers once occupied the position.

Sapsan dug into a box of parts to ready the day’s sorties. Mad scientists in the brigade produce some components; 3D printers churn out boxes to protect circuit boards, which the unit assembles by hand. Others tinker at workstations to unlock ways to make the drones fly farther and carry more.

Sapsan built each drone on-site, with various charges for different targets. Fragmentation munitions to hit foot soldiers. RPG warheads to destroy vehicles. For dugouts, thermobaric charges release fuel aerosol that creates a harder and longer concussive blast, which is violently efficient in a confined space.

At 24, Sapsan is a grizzled veteran. He enlisted days after Russia invaded and served in reconnaissance and infantry units. Working with drones appealed to his creative side. He used them in his prior job as a photography director, making music videos, films and advertising.

Dexterity from mastering card tricks gave him an edge learning to fly. Built for racing and hairpin turns, FPV drones rely on a pilot’s input for every motion. The controls can take weeks to master.

The first target of the day was a Russian T-90 tank. Sapsan’s thumb and index fingers worked the two sticks with a feather touch, controlling the drone’s pitch and yaw with tiny movements.

The drone combed the area but the tank vanished. Sapsan ditched it in a tree line, hoping to hit soldiers by happenstance.

He raised his goggles and lit a cigarette, a post-flight ritual. He fired up another after a second miss on a T-90. A third smoke followed a failed run at an armored personnel carrier. The signal was lost, possibly jammed. Three flights, three misses.

Sapsan huddled over components to build more drones, clipping zip ties and placing the ends in his helmet.

After about 100 flights, he pondered what he could do with more drones. He has helped clear trenches with pinpoint explosions to aid comrades in capturing prisoners. He has careened into the windshields of Russian supply trucks. He has collapsed the walls of buildings where Russians sought safety only for a drone to fly through a window.

The 47th drone unit produces and uses about 20 drones a day. Occasionally, the unit fundraises on social media. One unit member, Pavlo, said he buys parts with proceeds from his YouTube page.

“There are never enough drones,” Sapsan said.

Russian units operate FPV drones in the same way but Moscow seems to have greater supplies, said a deputy company commander in the 80th Separate Assault Brigade with the call sign Swift. The brigade recently helped liberate Klishchiivka near Bakhmut. Russian teams hit minor targets or deploy two drones at once, suggesting a deeper inventory, Swift said.

Countering FPV drones is difficult, Swift said. Electronic jamming or nets strewn over vehicles and trenches help, but the Russians know and use the same methods. “It’s like a chess game,” he said. “They’re winning it. Just in terms of quantity.”

Ukraine’s leaders said they want to do more. FPV drones have shown “sniper-like accuracy,” said Deputy Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov, who heads the country’s Army of Drones program, which is working to train 2,600 FPV drone pilots.

The FPV war can play out in bizarre ways. Because the analog signals are not encrypted, pilots often acquire the signal of other drones, Sapsan said — seeing its video, like ghosts in each other’s machines.

In one case, a Ukrainian pilot tapped into the feed of a Russian FPV drone, read the terrain and warned soldiers in danger. They were able to take cover, Sapsan said.

Russian soldiers have griped on social media that Ukrainian FPV drones make it harder to move around, and have redefined how far from the front is considered safe, said Bendett, the drone expert. The dynamic, he said, is fed by each side uploading videos of successful strikes.

“You almost never know where an FPV drone is coming from,” he said. “It’s a tremendous psychological effect.”

And there is also an effect — still not fully understood — on the drone operators. What does the act of remote killing do to someone simultaneously detached but intimately close to violence?

Sapsan dismissed the idea of a moral quandary. He sees his job as saving Ukrainians. “There are no feelings of any kind, no sympathy,” he said. “If it were not clear what we were fighting for, such as the campaigns in Vietnam and Afghanistan, then there would be anxiety and pain.”

“But everything is clear here,” he said. “I do not regret what I am doing.”

The air grew quiet in the afternoon. Soldiers tapped on their phones until a command center coordinator ushered them back into action.

The team’s fortunes improved. A near miss landed next to Russian soldiers, perhaps injuring some. Sapsan sent one drone crashing into a machine gun position and dropped another directly into a trench. Their streak ended after missing another machine gun nest.

Then, promising surveillance unfolded with the sighting of eight Russian soldiers entering a dugout. Sapsan grabbed a drone loaded with a thermobaric charge and sent it aloft.

After Sapsan cursed the wind, Actor, the navigator, reassured him: in theory, it would help propel the drone on its final attack run.

Ukrainian artillery rocked the area as Sapsan flew near, and Actor directed him to an intricate trench system in a strip of trees.

The drone was 200 meters away and closing in. Sapsan spotted the opening. His body tensed. His mouth was agape. He nearly stopped breathing.

He flicked his left stick down, sending the drone spiraling into the hole. His screen crackled with white noise.

“That’s a hit!” Actor said.

Sapsan raised his headset and peered at the drone feed. Smoke billowed from the target.

It was time for a cigarette.

Serhiy Morgunov in the Donetsk region and Anastacia Galouchka in Kyiv contributed to this report.

Video editing by Jason Aldag. Photo editing by Olivier Laurent.