[ad_1]

The U.S. economy’s post-Covid growth spurt has come amid one very big problem: lack of workers for jobs across sectors as they bounce back from the pandemic and now attempt to grow amid tighter financial conditions. The labor market, where job openings have reached as high as two for each available worker, is a force within the inflation that continues to challenge companies looking to hire skilled workers. Nowhere has the tight labor market been more extreme than in construction.

The construction sector is a fundamental backbone of the nation – without structures created by construction workers, Americans would have nowhere to eat, sleep, work, or live. And yet, the industry is currently battling the highest level of unfilled job openings ever recorded.

According to an outlook from Associated Builders and Contractors, a trade group for the non-union construction industry, construction firms will need to attract an estimated 546,000 additional workers on top of the normal pace of hiring in 2023 to meet the demand for labor. The construction industry averaged more than 390,000 job openings per month in 2022, the highest level on record, while unemployment in the sector of 4.6% was the second lowest on record.

A long-term labor force problem

There are simply not enough workers to keep up with the growing demand for houses, hospitals, schools, and other structures. What’s more, with the passage of Biden’s infrastructure bill, American municipalities have large sums of money to invest in the revitalization of their buildings, but no one to perform said revitalization. The number of online applications for roles in the construction industry fell 40% at the beginning of the pandemic and has remained flat since, according to ZipRecruiter data from April.

“Despite sharp increases in interest rates over the past year, the shortage of construction workers will not disappear in the near future,” said ABC Chief Economist Anirban Basu in a February release on its labor supply and demand outlook.

“There is a labor shortage. There are about 650,000 workers missing from the construction industry, and construction backlogs are now at a four-year high,” said Maria Davidson, CEO and Founder of Kojo, a materials management company in an interview with CNBC’s Lori Ann Larocco.

The labor challenges come at a time when the construction sector is facing other supply headwinds that arose since the pandemic.

“The landscape has dramatically changed since February 2020,” Davidson said. “Commercial construction materials prices are now 40% higher than they were back in February 2020. When you think about materials availability, it’s become dire. Panels and commonly used equipment in everything from electrical to mechanical installation are now more than a year in delay. And that’s made it very difficult for contractors all over the country to get the materials they need and be able to install them on time and keep projects on budget.”

Boston, MA – August 9: Construction worker Michael Elder took his hard hat off to wipe sweat off his face while working on the MBTA Green Line in 90-plus degree weather.

Boston Globe | Boston Globe | Getty Images

The construction sector’s labor issues are showing up across the economy.

“I think the biggest place we’re seeing it show up right now is in housing,” said Rucha Vankudre, an economist at Lightcast. “People just aren’t getting things built the way they want.”

“In cases where you’re building a big hospital project, as an example, you might have locked in the timeline that you expected to complete something by back in 2019 and now be suffering the consequences of the materials disruptions that we’re seeing,” Davidson said.

What’s more, Davidson cited “delays cascade” — when a contractor or construction company experiences a delay in one trade, or a disruption in the supply chain for one material, that will delay their next trade or next material acquisition as well.

For construction workers, pay is booming

For workers who seek construction jobs, the timing has never been better.

“They’re making more money. It’s a workers’ market,” said Brian Turmail, vice president of public affairs and strategic initiatives at Associated General Contractors of America. “The construction industry is now paying 80% more than the average non-farm job in the United States.”

There is a constant supply of work, and the opportunity to make additional income working overtime hours that would not be available if the labor pool wasn’t so tight.

Turmail cited an aging labor force as a reason for the continued shortage. Workers retire at earlier ages since it is such a physically demanding industry, and the labor force skews older. Construction firms have been incentivizing workers to delay their retirement and work as trainers or teachers.

Even under these pro-worker conditions, a shift in American work culture has played a role in limiting the attractiveness of the field to job seekers.

“It’s cultural,” Turmail said. “Mom doesn’t want her babies to grow up to be construction workers. For the last 40 years, we’ve been preaching a message nationally that the only path to success in life lies through a four-year college degree in some kind of an office.”

Working in construction can be extremely dangerous compared to other jobs, with the second-highest rate of occupational fatalities, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Vankudre said that construction as a career path is not particularly appealing to young people, and until the U.S. government and construction companies find a way to change that belief among the labor force’s newest generations, the shortage will linger.

Plenty of money to build, not enough to recruit and train

This process, according to Turmail, starts in schools.

“Firms are realizing that no one’s gonna solve the problem but themselves. So, they’re building stronger relationships with high school programs, even middle school programs. They’re finding ways to get students out to construction job sites to expose them to career opportunities,” Turmail said.

Construction firms are not the only ones working to bring new people into the industry. LIUNA, the Laborers’ International Union of North America, has efforts underway to reach more potential workers.

“We have a lot of different programs to bring new people into the construction industry,” said Lisa Martin, LIUNA spokeswoman. “Whether they’re justice-involved, bringing more women in, we have pre-apprenticeship programs, we have programs to help high school students graduate with skills to then start into apprenticeship programs. So we have a lot of different avenues to bring more people into the work into good paying jobs.”

Shifting the demographics of the existing construction workforce is a way to potentially alleviate some of the labor shortage.

“Construction is fighting workforce shortages with one hand tied behind its back,” Turmail said. “Women are half the workforce, and yet they’re somewhere around 6% to 7% of the craft workforce, the men and women who actually do the construction work in the hard hats and the boots. And if we can find a way to increase those percentages, we won’t even be talking about labor shortages.”

Immigration policy is another important lever for the construction industry.

“If you look at the demographics of the U.S., we don’t have enough workers. We’re just not going to for a very long time,” Vankudre said. “Given we can’t produce more workers in our own country, it makes sense that we would have to find them from other places. And I think that would definitely alleviate the sort of squeeze we’re feeling not just in construction, but really the whole economy.”

“We should also be looking at ways to allow more people to lawfully enter the country and work in construction careers, whether that’s a temporary work visa program that’s specific to construction, or broader comprehensive immigration reform – that needs to be part of the conversation about labor shortages in the construction industry,” Turmail said.

President Biden’s recent infrastructure bill magnifies the issue – money has been allocated for updating America’s infrastructure, but no money has been allocated for enticing new workers into the construction industry, or training new workers. This, according to Davidson, has worsened the labor shortage that already existed prior to the bill’s passage.

“More money is going to need to be spent on training additional workers, bringing people into this industry,” Vankudre said. “Because otherwise we are going to hit a point in the future where we’re just not building the things we want to, not because we don’t have the money, but because we don’t have the people.”

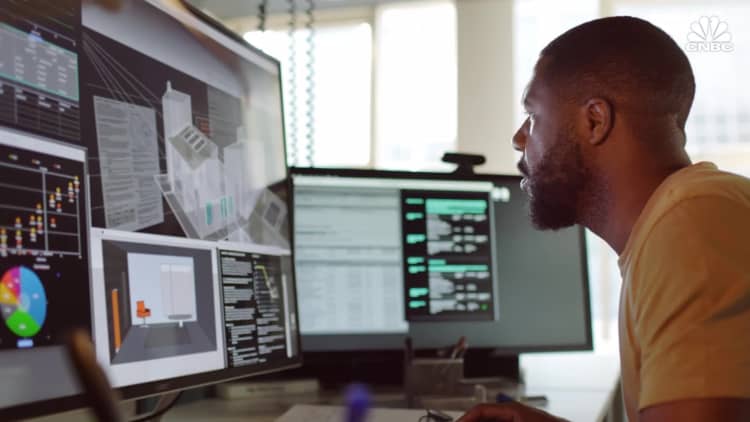

Watch the video above to learn more about how technology is helping to close the labor gap in the construction sector.

[ad_2]