The world’s attention has largely focused on the turbulence within Russia, where the aura of President Vladimir Putin is widely perceived to have been damaged by the short-lived insurrection of Wagner’s leader, Yevgeniy Prigozhin. But a Kremlin crackdown on Wagner would also have far-reaching consequences in Africa and the Middle East, where Wagner supplied lethal firepower to despots and strongmen while advancing Moscow’s international agenda.

In the Central African Republic and Mali, where Wagner has its biggest presence on the continent, residents said WhatsApp group chats and weekend conversations in the African nations were dominated by speculation about the fallout in their countries.

“Everyone is scared,” said a political analyst in Bamako, the capital of Mali, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to be candid about the tense situation. “Everyone knows that what happens in Russia will affect us.”

Officials and experts said it is too soon to know whether Wagner will retreat from Africa, or whether Prigozhin will be permitted to continue running the organization’s sprawling operations beyond Russia. For now, the group’s mercenaries were still visible at checkpoints and other security installations in Africa, according to witnesses and media reports.

Serge Djorie, the Central African Republic’s communications minister, did not respond to requests for an interview but sent a statement blaming Western media for causing “unnecessary friction.”

“The Central African Republic needs peace, nothing but peace, with people and countries willing to give their sincere support for the development of its people,” he said.

The government of Mali did not respond to a request for comment.

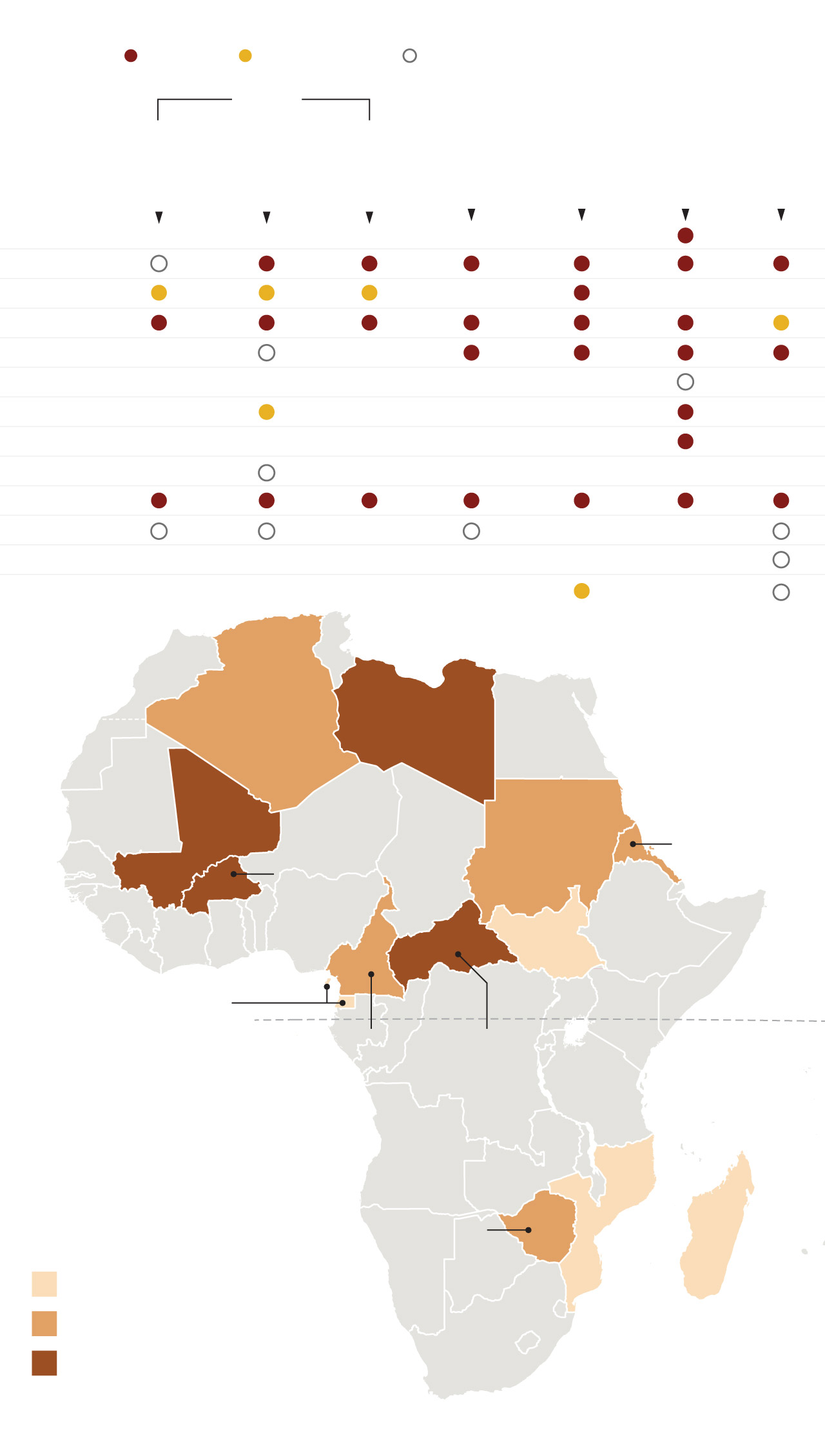

Prigozhin network involvement in Africa

Previously solicited or provided to regime

Explore/

extract

natural

resources

Conduct

offensive

combat

operations

Provide

personal

or regime

security

Advise

government

leadership

Provide

training or

equipment

Algeria

Libya

Burkina Faso

Mali

Sudan

South Sudan

Eritrea

Cameroon

Eq. Guinea

C.A.R.

Mozambique

Madagascar

Zimbabwe

Total number of Prigozhin network activities current

or discussed in each country

1-3 types of network activities

Graphic based on information from leaked classified material that was circulated in a Discord chatroom

and obtained by The Washington Post

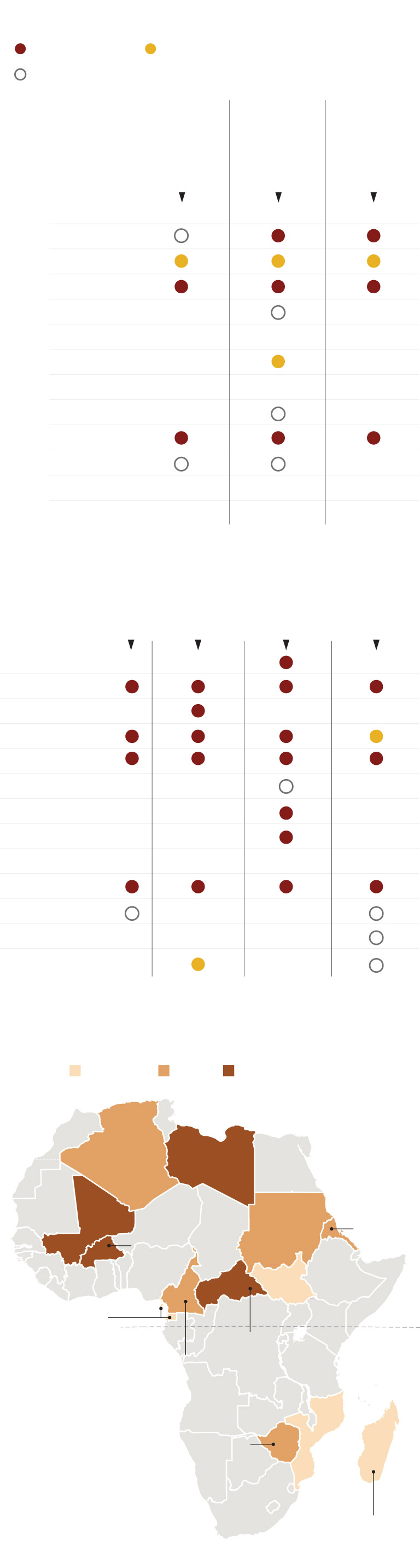

Prigozhin network involvement in Africa

Previously solicited or provided to regime

Conduct

offensive

combat

operations

Provide

training or

equipment

Provide

personal or

regime

security

Algeria

Libya

Burkina Faso

Mali

Sudan

South Sudan

Eritrea

Cameroon

Eq. Guinea

C.A.R.

Mozambique

Madagascar

Zimbabwe

Explore or

extract

natural

resources

Advise

government

leadership

Algeria

Libya

Burkina Faso

Mali

Sudan

South Sudan

Eritrea

Cameroon

Eq. Guinea

C.A.R.

Mozambique

Madagascar

Zimbabwe

Total number of Prigozhin network activities

current or discussed in each country

Note: Currently

not supporting

Graphic based on information

from leaked classified material

that was circulated in a Discord

chatroom and obtained by The Washington Post

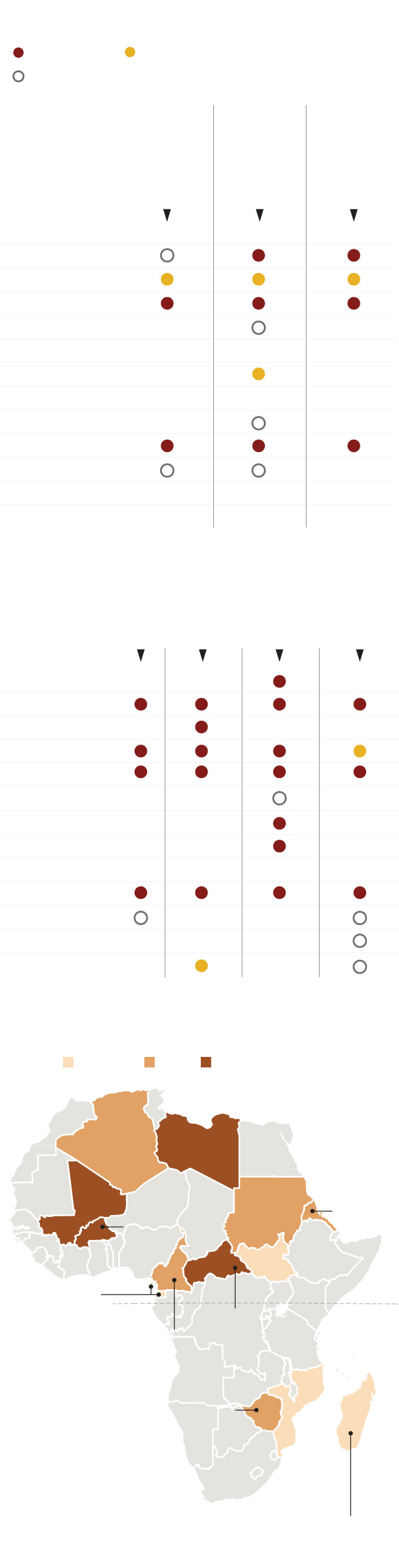

Prigozhin network involvement in Africa

Previously solicited or provided to regime

Conduct

offensive

combat

operations

Provide

training

or

equipment

Provide

personal or

regime

security

Algeria

Libya

Burkina Faso

Mali

Sudan

South Sudan

Eritrea

Cameroon

Equa. Guinea

C.A.R.

Mozambique

Madagascar

Zimbabwe

Explore/

extract

natural

resources

Advise

government

leadership

Algeria

Libya

Burkina Faso

Mali

Sudan

South Sudan

Eritrea

Cameroon

Equa. Guinea

C.A.R.

Mozambique

Madagascar

Zimbabwe

Total number of Prigozhin network activities

current or discussed in each country

Note: Currently

not supporting

Graphic based on

information from leaked

classified material that was

circulated in a Discord chatroom

and obtained by The Washington Post

Many Western officials and regional authorities are skeptical that an oblique truce struck between Prigozhin and the Kremlin can stand for any extended period, potentially threatening Russia’s interests in Africa as well as the stability of its allies.

“The threat analysis of Wagner in Africa will need to be revised,” said J. Peter Pham, a distinguished fellow with the Atlantic Council. “It may be a lowering of the threat assessment in the long term, though in the short term, things could worsen. But that change is coming is fairly clear.”

The stakes were underscored this year by assessments contained in leaked U.S. intelligence files, which raised alarms about Wagner’s plans to establish a “confederation” of anti-Western states on the continent, where the group has struck deals providing paramilitary capabilities in exchange for lucrative concessions giving it control over assets ranging from diamond mines to oil wells. Researchers and the U.S. military have estimated there are several thousand Russian mercenaries on the continent.

Western officials and analysts said internal divisions in Russia could provide an opportunity for the Biden administration and other Western powers to claw back influence in countries where Wagner is active and prevent the group from gaining new footholds.

In Mali — where authorities moved further into Russia’s orbit this month when they asked the U.N. peacekeeping force to withdraw, leaving Wagner as their main international military partner — officials have not commented publicly since news broke of Prigozhin’s rebellion. Leaders don’t want to be seen as choosing sides between Putin and Wagner, said the political analyst in Bamako, as they know they need Russian support to fight spiraling Islamist violence.

One of the many unanswered questions surrounding the terms of the truce, which involves an uncertain exile for Prigozhin in Belarus, is whether Putin allowed the Wagner leader to retain control of his overseas operations.

“Is that the price?” asked Bob Seely, a member of the British Parliament who serves on the foreign affairs committee, which has been conducting an investigation of Wagner in Africa for the past two years. “Is his continued control over them part of the price of giving up his Wagner formations inside Russia and Ukraine?”

Even if Prigozhin was promised that he could run Wagner’s outposts, officials voiced skepticism that the Kremlin would ultimately stick to that bargain, in part because of Africa’s economic and geopolitical importance to Moscow. One of the benefits of Wagner to Moscow was that it allowed Russia to operate in Africa “both officially and unofficially,” analysts said, with the group — which has been accused of human rights violations — often promoting Kremlin interests but also operating with a level of plausible deniability.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in an interview Monday with RT, a Russian state media outlet, said “military from Russia” will continue to work with the Central African Republic and Mali, but he didn’t mention Wagner by name, noting only that those countries had “requested a private military company” when they were “abandoned by the French and other Europeans.”

Pham, of the Atlantic Council, said that it was not yet clear whether Wagner will ultimately be forced to operate more closely with the Russian state or if it instead might “fracture into half a dozen mini-Wagners” that operate more autonomously. But he said that what seems evident is that, at least in coming months, Prigozhin “is not going to be focused on his African ventures.”

For Washington, which has been escalating efforts to counter Wagner in Africa in the past year, this moment could be an opportunity and may cause a reevaluation of policies, according to current and former officials and analysts.

The Biden administration has paused sanctions that it had planned to unveil in coming days related to Wagner’s gold business in the Central African Republic, according to a current government official and a former one. U.S. officials wanted to avoid the appearance of siding with either Wagner or the Kremlin, they said.

State Department spokesman Matthew Miller declined to confirm that sanctions were delayed, but said the United States always times its sanctions “for maximum impact or maximum effect” and pledged that the United States would continue to hold the group “accountable.”

Cameron Hudson, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said that it will be important to get a “clearer understanding” of the relationship going forward between Wagner and the Kremlin, to ensure that Washington’s policies targeting Wagner — whose head in Mali has already been the subject of U.S. sanctions — do not end up inadvertently helping Putin.

Although Hudson said there are scenarios that could have deeply negative consequences for African countries and their relations with the West — including if thousands of Wagner’s soldiers move out of Ukraine and onto the continent — the overall situation “only reinforces the point that Washington has been making to African governments: ‘Wagner doesn’t bring stability — it only brings chaos.’”

Efforts by the Biden administration to inoculate struggling African countries from the overtures of Prigozhin and his top aides included an interagency trip this past fall of White House, Defense Department and State Department officials to Mauritania, Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso.

The administration is considering providing governments in that region with security assistance, which it hopes can lure governments out of Wagner’s obit or prevent them from joining in the first place. But the endeavor is complicated by recent coups in some Sahelian countries, including Burkina Faso, which a senior State Department official said Wagner is already providing some equipment to.

Authorities in Burkina Faso are seeking security assistance to fend off a powerful Islamist militant insurgency, but U.S. officials are restricted in what they can provide as a result of the coup and have concerns about any assistance being used to commit human rights abuses by Burkina Faso authorities.

In the Central African Republic, the U.S. official characterized President Faustin-Archange Touadéra as having “buyer’s remorse” about his decision to work with Wagner because of the extent of the group’s control over the country’s resources. There, conversations are ongoing about what type of support the United States might be able to provide, the official said.

But Hudson and other analysts warned that any such discussions need to take into account the services that Wagner is offering, including direct military support and protection of the incumbent regimes. The discussion in some ways “is sort of apples and oranges,” Hudson said. “Wagner is providing security, and we’re offering textbooks.”

In interviews in Bamako, Malians said they worried about the fallout. Ben Sangare, a 43-year-old consultant, put it bluntly: “It will be difficult,” he said, “for Russia to deal with its own problems and the Sahel region at the same time.”

Mahamadou Sidibé, 45, said that although it seems unlikely that Mali would take back its request for the U.N. withdrawal, he said the chaos has eroded trust in Wagner and Russia.

“It exposed Russia’s leadership,” he said, “and it allowed me to see some of Russia’s flaws.”

Hudson reported from Washington and Miller from London. Mamadou Tapily in Bamako, Mali, and Mary Ilyushina in Riga, Latvia, contributed to this report.