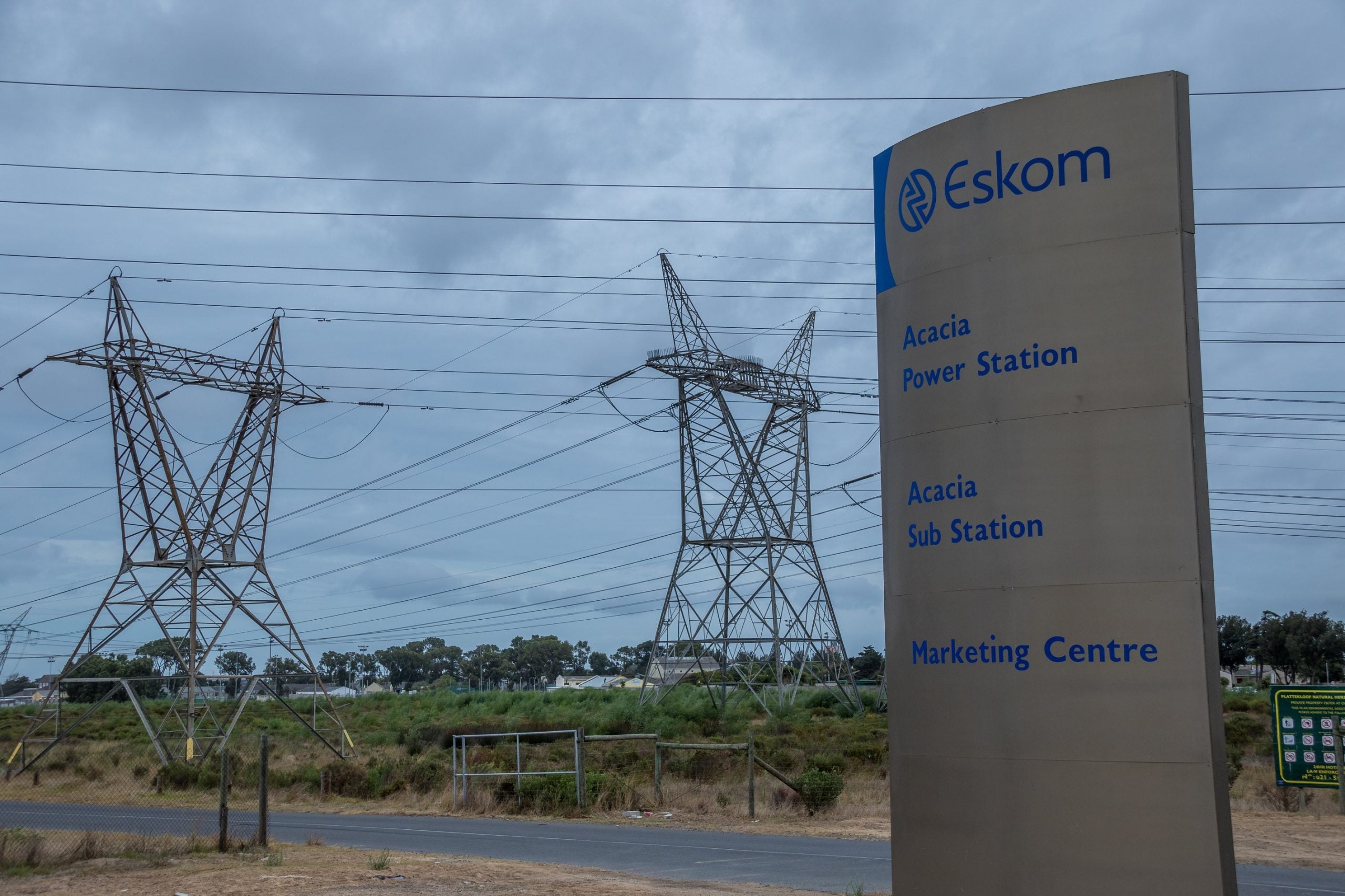

South Africa’s food manufacturers have been forced to invest in alternative energy supply sources against a backdrop of power outages forced on the national electricity provider Eskom.

What is the issue?

Simply put, South Africa is in the midst of an energy crisis, which is limiting the available supply of electricity.

It’s nothing new – the country has suffered power outages for more than a decade – but it has got worse of late. The country’s state-owned power company, Eskom is riddled with debt, has old infrastructure, power stations that do not work properly and was recently crippled by a strike.

South Africa relies on aging coal-fired power stations for most of its electricity. In 2020, just 7% of its energy came from renewable sources, according to the International Energy Agency.

South Africans faced electricity cuts for 288 days last year, while this year there have been electricity blackouts (effectively rolling power cuts) affecting households and businesses for up to ten hours a day as grid operators carry out so-called load-shedding – regular periods of shutting down supply to save energy.

Ajay Gupta, a country analyst with research and analysis company GlobalData – Just Food’s parent company – sums it up: “It is quite visible that the country is struggling with load-shedding along with increasing unemployment and rising inflation which is negatively affecting all areas of business and industry.”

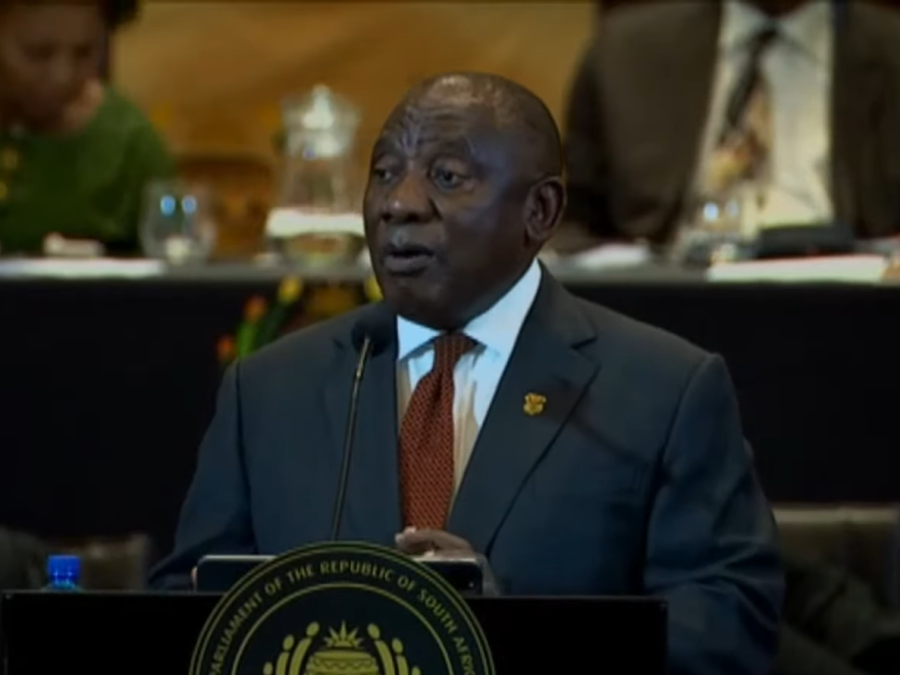

South Africa’s leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa, declared a state of disaster earlier this year to try and tackle the crisis and has appointed a minister of electricity who has the daunting task of formulating a response to the emergency.

Addressing the nation, Ramaphosa said: “We must act to lessen the impact of the crisis on farmers, on small businesses, on our water infrastructure, on our transport network and a number of other areas and facilities that support our people’s lives.”

The Consumer Goods Council of South Africa (CGCSA) sent the president an open letter calling for government action to support the food and beverage industry.

However, things could get worse on the energy front before they get better.

Eskom so far has not gone beyond stage six power cuts, which require 6,000 megawatts (MW) to be shed from the national grid. However, the company has said it may have to move to stage eight, which would require up to 8,000MW to be shed, translating to 16 hours of outages in a 32-hour cycle, because of increased demand in the winter months. Winter started this month in the southern hemisphere.

And to add to the country’s woes, it is facing up to the prospect of a water crisis as South Africa’s creaking water infrastructure is struggling to keep up with the demands of an ever-increasing population.

According to the World Bank, South Africa boasts the 33rd largest economy and the 23rd largest population on the planet – with 59 million inhabitants – but is it becoming a failed state?

No, says Iain Williamson, CEO of local financial heavyweight Old Mutual, but urgent action is required.

He said recently: “The current political environment is characterised by policy failures, endemic corruption and stagnant service delivery. These issues contribute to a sense of paranoia surrounding proposed solutions. Moreover, factors such as social unrest, fear of a grid collapse, and the potential for sanctions, further undermine South Africa’s social capital and erode confidence levels.”

However, Williamson said South Africa’s economy “has demonstrated remarkable resilience in 2023, exceeding expectations despite the challenges posed by the disconcerting cycle of load-shedding”.

And he suggested we are seeing “remarkable progress in private-sector energy generation”, especially in renewables.

How is the energy crisis impacting the country’s food production?

Data released last week revealed South Africa’s food and drinks manufacturing sector had performed well, relatively speaking, partly because the industry is not as electricity-intensive as other types of manufacturing.

Also, investments in renewable energy and power-cut mitigating measures to alleviate long-running problems have helped businesses in the sector to cope.

But the country’s largest food manufacturers are far from being complacent about the situation and the impact it is having on their operations.

Earlier this month, Premier Group revealed its profits had increased despite the power cuts.

For the year ended March 31, it posted a near 40% rise in profit.

The confectionery-to-pasta maker, behind brands such as Blue Ribbon bread and CIM biscuits, said it managed to pass on the costs of the country’s rolling blackouts but warned a possible increase in power outages could leave it struggling to meet customer demand.

Premier said it had spent ZAR32m ($1.66m) on diesel generators but CEO Kobus Gertenbach told news agency Reuters that had not proved too onerous in terms of the overall picture.

“Our general ability in terms of being able to run generators to operate bakeries is actually not cost prohibitive in relation to the category so the amount of cost that it adds is a couple of cents a loaf and you can pretty much quite easily recover it in the market,” he said.

However, Gertenbach said around 10% of total flour milling production was lost during the period because of the power cuts.

And he further warned “in my view, [Eskom moving to load-shedding] level eight would start to impact our ability to continue to produce enough product to service our market”.

Tiger Brands, South Africa’s largest food group, said at the end of May it expects the power cuts to lead to a rise in costs that will squeeze its income.

The Jungle Oats, Albany bakery and Cresta rice brands owner, commenting as it released its six-month results said the power cuts cost it R37m in the grains sector alone.

In a statement, it said: “Operating costs are expected to rise significantly as a consequence of higher levels of load-shedding during the winter season.”

Local peer Libstar, which has a wide-ranging product portfolio encompassing baby food, soup, pasta and dairy, also warned it is likely to face tough conditions for the rest of the year.

In commentary around the release of its annual results in March, it said load-shedding had added R39m to its operating costs and that it made a R13m capital investment in generators during the year with an additional R6.3m spent on generator capacity since January 2023.

South African poultry group Astral Foods, meanwhile, revealed at the end of May its operating profit had slid 89% year-on-year in the six months to the end of March.

It said it had incurred R741m in costs linked to load-shedding.

In a statement, Astral said: “All capital expenditure has been placed on hold except that required for necessary maintenance and emergency measures in electricity and water supply.”

RFG Holdings, which has a product portfolio ranging from canned fruit and vegetables to baked and frozen goods, has also been impacted by the power outages but, like Premier Group, has seen its profits surge.

In the six months to 2 April, profits rose by 36.7% year-on-year on the back of 14.8% food price inflation.

However, RFG said load-shedding continued to impact production output and costs.

CEO Pieter Hanekom said the group had invested extensively in back-up generators over the past seven years, and operational management had performed well in difficult circumstances to limit the impact of load-shedding on factory efficiencies.

He said diesel costs to operate generators totalled R37.8m for the six-month period.

“At the current levels of load shedding, the average weekly diesel cost to operate generators amounts to approximately R2m,” he said.

Speaking to analysts after the results were released at the end of last month, Hanekon said: “The ongoing load-shedding has had a big impact on our business.”

How can the crisis be solved?

Ramaphosa was criticised earlier in the year for not putting enough meat on the bones of his strategy to solve the energy crisis after he declared a state of disaster.

But, in an address this week, he outlined some of the measures the government has taken and is planning to take.

He admitted that “given the persistence of load shedding, for example, few people are able to contemplate the impact of a transformed energy landscape”, adding “we are making progress towards ending load-shedding – transforming the electricity market to make it more competitive and cost-effective is critical to the country’s future”.

He added: “Many of these reforms are being brought about by legislative and regulatory changes, which may not inspire many people, but which have a substantial impact on people’s lives and the performance of the economy.”

He revealed licensing requirements for generation projects of any size have been removed.

“As a result, more than 100 projects are now in development, representing over 10,000MW of new generation capacity and R200bn of private-sector investment,” he said.

He said tax incentives for rooftop solar are being implemented for businesses and households and significantly “Eskom is being unbundled into separate entities for generation, transmission and distribution” while its debt burden is being addressed through ZAR254bn in debt relief, subject to strict conditions.

“This will enable the company to make necessary investments in its infrastructure,” Ramaphosa said.

To enshrine some of these proposals in law, the Electricity Regulation Amendment Bill is being finalised for tabling in the country’s parliament.

“These developments are part of establishing for the first time in our country a competitive market for electricity generation,” Ramaphosa added.

The president’s last point is likely to be music to the ears of Old Mutual’s Williamson who is keen to see a ramping up of private-sector involvement in energy generation in the country.

Writing before the president’s statement, he said public-private partnerships need to be considered “because we have a proven framework and model to draw upon”.

He added: “The lessons learned during the Covid-19 pandemic have highlighted the significance of these partnerships in achieving successful outcomes. By leveraging these partnerships, we can effectively navigate the current challenges and work towards a brighter future for the country.”

What next for food manufacturers?

The food manufacturing industry may have liked to have seen specific intervention on its behalf – as a key industry – as requested by the CGCSA in its open letter to the president earlier in the year. There is perhaps a case that it should be treated as critical infrastructure that could be exempt from load-shedding, like hospitals and water treatment plants.

While the action plan announced by Ramaphosa will be welcomed, food groups are unlikely to be expecting to see results overnight.

And while they have been able to claw back some of the costs of investing in on-site diesel generators or solar installations through pricing actions, this may not be an option moving forward.

Astral said in May that a “macro-economic crisis” in South Africa was putting disposable income “under severe pressure”.

It added: “The continuous costly disruptions to agri-processing businesses and the integrated food production value chains, have left South Africa with deepening hunger and poverty levels, especially amongst the most vulnerable of communities, and an even greater threat to food security is plausible.”

And, as we have heard, capital investment in other projects is largely on hold at some businesses while there is a need to deal with the energy crisis.

RFG said its renewable energy programme had been accelerated in response to the sustained levels of load-shedding.

“Solar installations at a further four production facilities are due for completion in the second half of the financial year and a further three in the 2024 financial year,” it said.

The major South African food companies are by and large performing well, as is the sector as a whole, but they will be hoping the country’s politicians will be able to deliver on their promises to allow them to prosper in the future.