John Stones playing in midfield is no longer a new concept but this, in a Champions League final, was something else. “I played as more of a No 8 today,” he grinned afterwards, “which I loved.”

His enjoyment was obvious, even in the context of an edgy encounter. While others looked rushed, implored by Pep Guardiola to “relax”, Stones was serene, taking the ball under pressure then slaloming away from defenders deep in Inter Milan territory.

He left the pitch, this 29-year-old centre-back from Barnsley, having made the most dribbles in a Champions League final since Lionel Messi in 2015. Little wonder the Manchester City fans inside the Ataturk Olympic Stadium gave him a standing ovation.

Pep Guardiola showed his appreciation too, holding an arm around his shoulder as they soaked it all up during the celebrations afterwards. The City boss might just reflect on the decision to push Stones into midfield as the catalyst for this historic achievement.

Stones was there in all the key moments, after all, starting every knockout game from quarter-finals to final in a midfield berth and playing the same role in the FA Cup final win over Manchester United. He was similarly influential in the Premier League run-in.

All this from a player whose City career looked over only a few years ago. In the 2019/20 season, he wasn’t trusted to start a single Champions League game, let alone play in midfield. That summer, the club spent more than £100m on Ruben Dias and Nathan Ake.

Stones, out of the England squad as well as out of favour with his club at that point, recently described it as “one of the hardest times of my career” but his perseverance was rewarded. Now, his talent is shining through. “An incredible player,” says Guardiola.

It is of course thanks to Guardiola, as well as Stones himself, that he has flourished, the Catalan finding a role for him that serves both to unleash his technical ability and flummox City’s opponents.

It was in fact early in the season, before the World Cup, during which he shone as a traditional centre-back for England, that Guardiola began to experiment with Stones, using him as an inverted right-back while Kyle Walker was recovering from a groin injury.

Stones was of course not the first player to be used by Guardiola in that position, the purpose of which is to allow City to outnumber their opponents in midfield and push their wingers high and wide, while also being compact enough to deal with counter-attacks.

But this was not like Rico Lewis, Oleksandr Zinchenko or Joao Cancelo playing the role. Stones could provide the same level of composure and technique as those players in possession, but crucially he came to it as a “proper defender”, to use Guardiola’s term.

City, already using Ake on the opposite side, immediately became more solid, but it was only in March that Stones’ role morphed into its current guise. Suddenly, he looked more like a midfielder occasionally dropping in at right-back than a right-back popping up in midfield.

The change of emphasis can be traced back to City’s 7-0 thrashing of RB Leipzig in the second leg of their last-16 tie at the Etihad Stadium on March 14, when Stones played alongside Rodri for the first time, ahead of a back three of Manuel Akanji, Dias and Ake.

His performance in that game was flawless. Literally. He did not misplace a single pass. His 63rd-minute substitution, intended to conserve his energy, hinted at his growing importance to Guardiola.

Between that point and the end of the campaign, during the small hours of the night in Istanbul, Manchester City kept eight clean sheets in 20 fixtures – the last of which came when it was most needed – and never conceded more than one goal, with Stones a ubiquitous presence.

Erling Haaland and Kevin De Bruyne went down as the star performers, finishing first and second respectively in the PFA Player of the Year voting, but the security provided by Stones’ switch into the centre was arguably the bigger factor in City’s success.

Indeed, it was telling that Inter Milan’s best chances on Saturday night came after Stones had made way for Walker, when Inter were able to pin Guardiola’s team back for the first time in the contest.

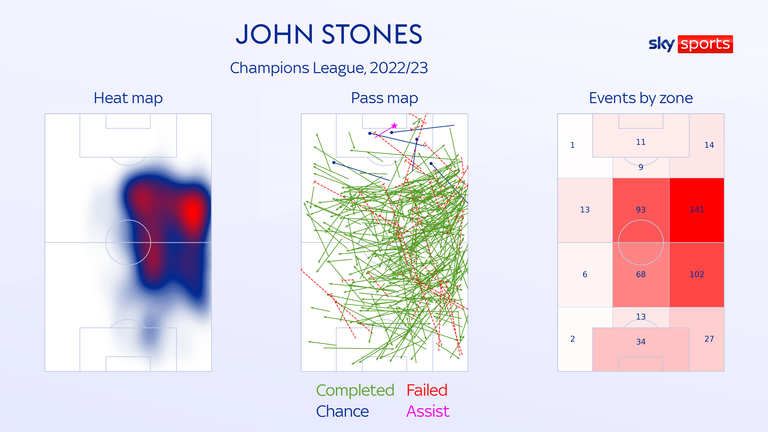

Not that Stones’ role had been a particularly defensive one before that. In fact, as well as completing seven out of eight attempted dribbles, most of which came in Inter’s half as City were trying to break Simone Inzaghi’s side down, Stones had more touches in the opposition box than his own.

In a fraught first half, even his team-mates seemed surprised by the freedom of his movement. Stones was always asking for the ball but did not always get it. “We were so anxious, we could not find the free man, John Stones,” reflected Guardiola later. “But it was a question of being patient.”

It changed after the break, with City gradually finding their rhythm and Stones central to it. In the second half, he had more touches (31 to 26) and made more passes (20 to 17) – and that despite being substituted for the last eight minutes, plus stoppage time.

He was even involved in the build-up to the goal, playing the first forward pass of the move by feeding Bernardo Silva to his right, then hovering on that flank to subsequently help create the space Akanji needed to send Silva in behind to tee up Rodri.

“Football is so fluid now,” Stones had said beforehand. “It’s about understanding your responsibility, knowing where your team-mates are. Being higher up the pitch, I really enjoy the fluidity. Teams play with so many players behind the ball. We have to be intricate in the final third.”

Stones, while also providing the defensive security they previously lacked, gave Manchester City all of that. The centre-back-turned-No 8 ultimately proving the catalyst for a treble-clinching finale.