Vint Cerf, one of the founding fathers of the internet, has some harsh words for the suddenly hot technology behind the ChatGPT AI chatbot: “Snake oil.”

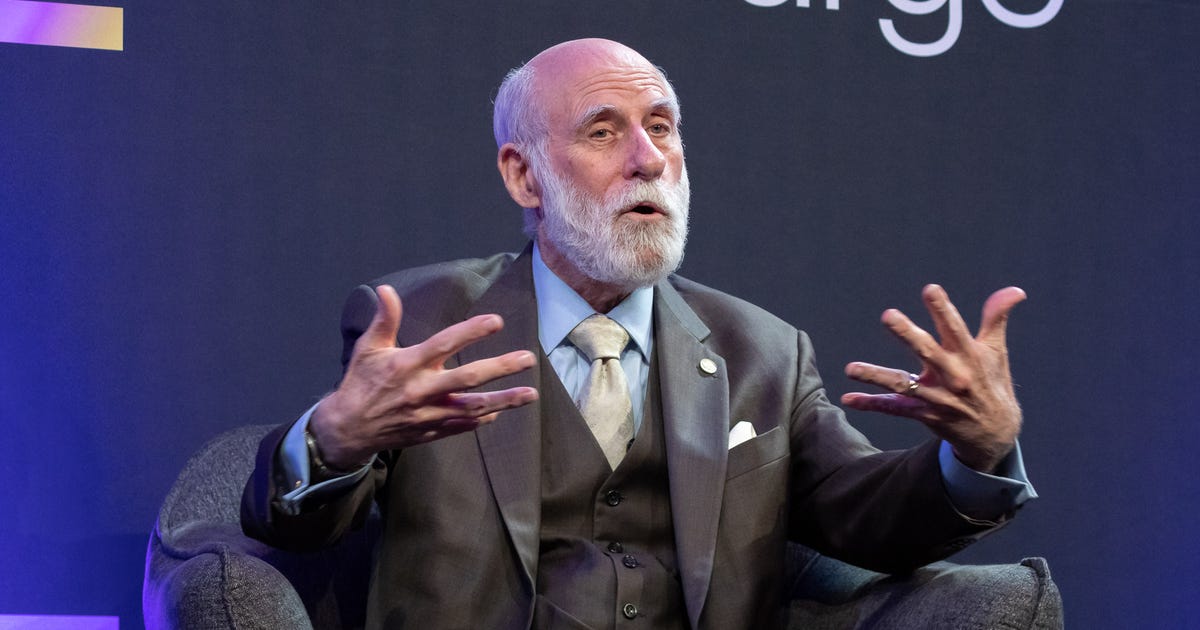

Google’s internet evangelist wasn’t completely down on the artificial intelligence technology behind ChatGPT and Google’s own competing Bard, called a large language model. But, speaking Monday at Celesta Capital’s TechSurge Summit, he did warn about ethical issues of a technology that can generate plausible sounding but incorrect information even when trained on a foundation of factual material.

If an executive tried to get him to apply ChatGPT to some business problem, his response would be to call it snake oil, referring to bogus medicines that quacks sold in the 1800s, he said. Another ChatGPT metaphor involved kitchen appliances.

“It’s like a salad shooter — you know how the lettuce goes all over everywhere,” Cerf said. “The facts are all over everywhere, and it mixes them together because it doesn’t know any better.”

Cerf shared the 2004 Turing Award, the top prize in computing, for helping to develop the internet foundation called TCP/IP, which shuttles data from one computer to another by breaking it into small, individually addressed packets that can take different routes from source to destination. He’s not an AI researcher, but he’s a computing engineer who’d like to see his colleagues improve AI’s shortcomings.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT and competitors like Google’s Bard hold the potential to significantly transform our online lives by answering questions, drafting emails, summarizing presentations and performing many other tasks. Microsoft has begun building OpenAI’s language technology into its Bing search engine in a significant challenge to Google, but it uses its own index of the web to try to “ground” OpenAI’s flights of fancy with authoritative, trustworthy documents.

Cerf said he was surprised to learn that ChatGPT could fabricate bogus information from a factual foundation. “I asked it, ‘Write me a biography of Vint Cerf.’ It got a bunch of things wrong,” Cerf said. That’s when he learned the technology’s inner workings — that it uses statistical patterns spotted from huge amounts of training data to construct its response.

“It knows how to string a sentence together that’s grammatically likely to be correct,” but it has no true knowledge of what it’s saying, Cerf said. “We are a long way away from the self-awareness we want.”

OpenAI, which earlier in February launched a $20 per month plan to use ChatGPT, has been clear about about the technology’s shortcomings but aims to improve it through “continuous iteration.”

“ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers. Fixing this issue is challenging,” the AI research lab said when it launched ChatGPT in November.

Cerf hopes for progress, too. “Engineers like me should be responsible for trying to find a way to tame some of these technologies so they are less likely to cause trouble,” he said.

Cerf’s comments stood in contrast to those of another Turing award winner at the conference, chip design pioneer and former Stanford President John Hennessy, who offered a more optimistic assessment of AI.

Editors’ note: CNET is using an AI engine to create some personal finance explainers that are edited and fact-checked by our editors. For more, see this post.