A version of this story appears in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

CNN

—

New York to San Francisco. Baltimore to Portland. Boston to Los Angeles, and countless cities in between.

Protesters once again took to the streets over the weekend to decry police brutality after the release of video capturing the violent Memphis police beating that led to the death of 29-year-old Tyre Nichols.

On Sunday morning, Nichols’ family attorney made note of the outrage as he aimed a simple but pointed message at Washington.

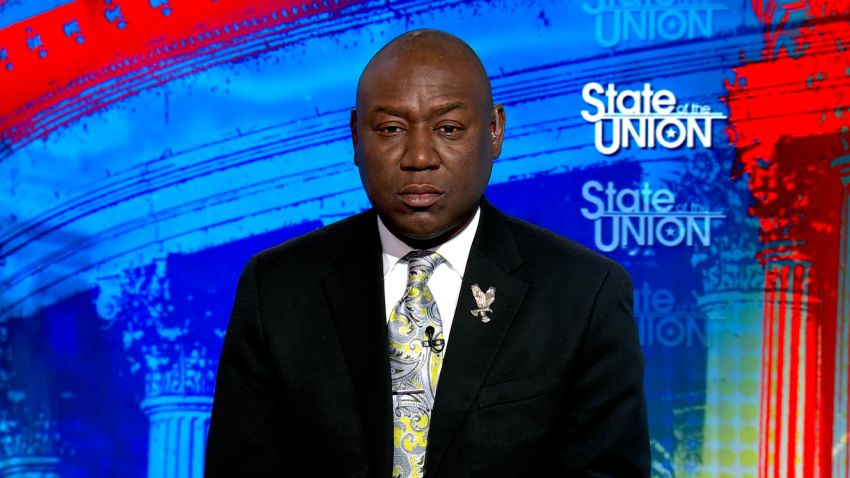

“Shame on us if we don’t use [Nichols’] tragic death to finally get the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act passed,” Ben Crump said on CNN’s “State of Union.”

Bash asks Crump if he’s confident officers will be convicted. Hear his response

President Joe Biden referenced the failed legislation in his statement about Nichols on Friday, and many leaders – from the chairs of the Senate and House Judiciary Committees, Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Republican Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio – are acknowledging a potential role for federal legislation.

The Congressional Black Caucus is requesting a meeting with Biden this week to push for negotiations. “We are calling on our colleagues in the House and Senate to jumpstart negotiations now and work with us to address the public health epidemic of police violence that disproportionately affects many of our communities,” CBC Chair Steven Horsford, a Nevada Democrat, wrote in a statement on Sunday.

Gloria Sweet-Love, the Tennessee State Conference NAACP president, called on Congress to step up during a Sunday evening news conference in Memphis. “By failing to craft and pass bills to stop police brutality, you’re writing another Black man’s obituary. The blood of Black America is on your hands. So stand up and do something.”

But with Congress as divided as ever, it appears public outrage is once again on a collision course with Washington partisanship.

Here’s what you need to know about the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, why it failed, and what chances it stands in the current political climate.

The legislation, originally introduced in 2020 and again in 2021, would set up a national registry of police misconduct to stop officers from evading consequences for their actions by moving to another jurisdiction.

It would ban racial and religious profiling by law enforcement at the federal, state and local levels, and it would overhaul qualified immunity, a legal doctrine that critics say shields law enforcement from accountability.

According to a fact sheet on the legislation at the time, the measure would also allow “individuals to recover damages in civil court when law enforcement officers violate their constitutional rights by eliminating qualified immunity for law enforcement.”

The fact sheet also states that the legislation would “save lives by banning chokeholds and no-knock warrants” and would mandate “deadly force be used only as a last resort.”

The bill twice cleared the House under Democratic control – in 2020 and 2021 – largely along party lines. But it never went anywhere in the Senate, even after Democrats won control in 2021, in part, because of disagreements about qualified immunity, which protects police officers from being sued in civil court.

Democratic Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey and Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina spent some six months trying to hash out a deal that could win 60 votes in the Senate, but talks were stymied by a number of complicated issues.

“It was clear at this negotiating table, in this moment, we were not making progress,” Booker told reporters in the spring of 2021. “In fact, recent back-and-forth with paper showed me that we were actually moving away from it. The negotiations we were in stopped. But the work will continue.”

With the legislation stuck, Biden signed a more limited executive order to overhaul policing on the second anniversary of Floyd’s death. It took several actions that can be applied to federal officers, including efforts to ban chokeholds, expand the use of body-worn cameras and restrict no-knock warrants, among other things.

But the president cannot mandate that local law enforcement adopt the measures in his order; the executive action lays out levers the federal government can use, such as federal grants and technical assistance, to incentivize local law enforcement to get on board

And since then, little has happened on the federal legislative front.

Here’s the reality: the road for police reform has only become more challenging in the new Congress now that House Republicans, who have placed their priorities elsewhere, are in the majority.

Senate Democrats picked up one more seat in last year’s midterm elections to pad their majority, but they’re still far short of the 60 votes that would be need for such an effort to succeed. That means any policing overhaul that can find meaningful support in Congress will likely be stripped of the kind of measures that protesters are calling for.

State officials have been initiating investigations into local police departments, recognizing that the federal government can’t take on every case nationwide.

And, in some cases, local governments have taken their own steps. In the year after Floyd was killed, at least 25 states had considered some form of qualified immunity reform. In 2021, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, signed into law a series of police reforms that created a system to decertify law enforcement officers found to have engaged in serious misconduct – joining the majority of states that have similar decertification authorities.

But, for many, it’s not nearly enough. Read this CNN Opinion piece from Sonia Pruitt, a retired Montgomery County, Maryland, police captain:

“Many have noted the police assault on Nichols is reminiscent of that on Rodney King, a Black man whose beating at the hands of Los Angeles police officers in 1991 was captured on video. But the beating of Nichols is actually much worse because it shows that after nearly 32 years, the needle of police reform has barely moved, and seemingly minor traffic violations continue to lead to the deaths of Black and other minority men and women in police encounters.”