A black hole’s invisibility could be considered its greatest strength. Across the fabric of space, these silent beasts drink every drop of light trickling into their gravitational pulses, bottle these rays from the observable universe, and in darkness, wait for a helpless star to appear. Then, they attack.

Now, scientists have announced NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope caught what comes next in such a cosmic nightmare — also known as a tidal disruption event, during which a black hole feasts on its prey, or “accretes” a star. Astronomers shared the news Thursday at an American Astronomical Society meeting.

“Typically, these events are hard to observe. You get maybe a few observations at the beginning of the disruption when it’s really bright,” Peter Maksym of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, said in a statement. “We saw this early enough that we could observe it at these very intense black hole accretion stages.”

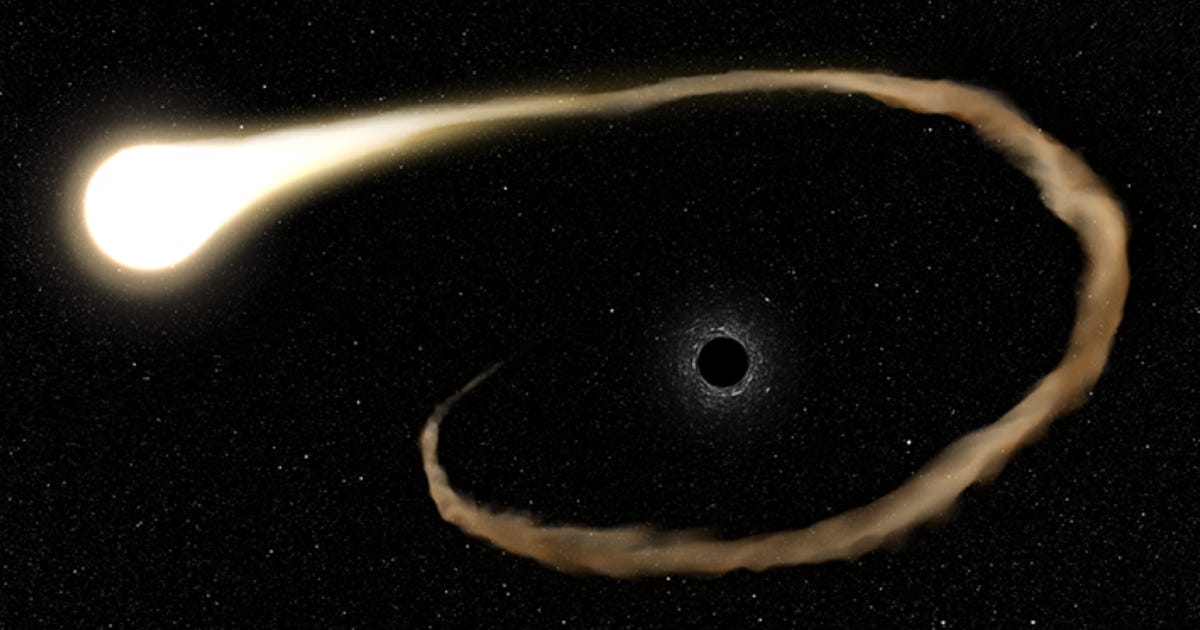

Caught in a chasm’s deathly gravitational embrace, this star’s spherical shape was seen aggressively mutated into a twisted strand of glowing matter. Before Hubble’s glassy eyes, the star was viciously ripped apart until it looked like a warped whirlpool of fairy dust, encircling its predator and leaving behind a flaming tail to illuminate the otherwise blank void of space.

Aptly, this is sometimes referred to as a black hole “spaghettifying” matter because even the strongest of objects with the misfortune of treading too close to the gravitationally extreme pit gets turned to flimsy, noodly shreds.

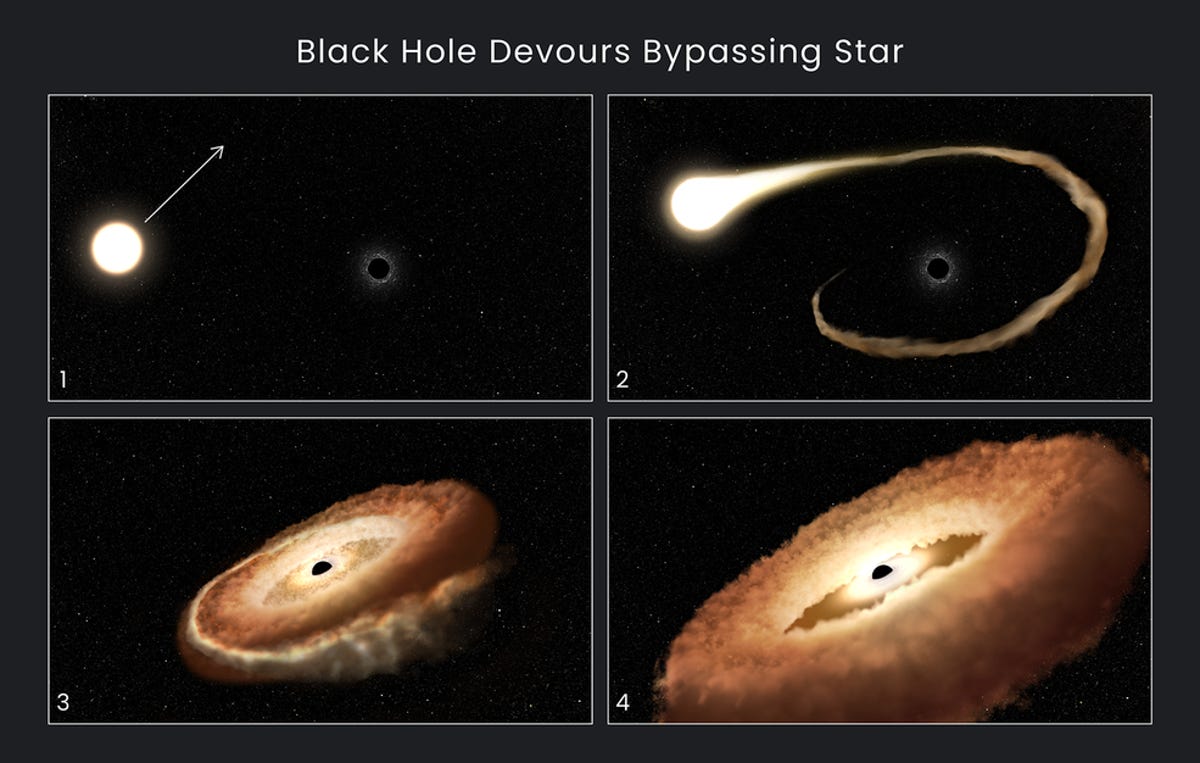

This sequence of artist illustrations shows how a black hole can devour a bypassing star. 1. A normal star passes near a supermassive black hole in the center of a galaxy. 2. The star’s outer gasses are pulled into the black hole’s gravitational field. 3. The star is shredded as tidal forces pull it apart. 4. The stellar remnants are pulled into a doughnut-shaped ring around the black hole, and will eventually fall into the black hole, unleashing a tremendous amount of light and high-energy radiation.

NASA, ESA, Leah Hustak (STScI)

Meanwhile, the black hole devoured its now-doughnut of a star — scientifically called a torus at this point — pulling in the tortured orb’s gasses while simultaneously spitting material out as though they’re bones of a scrumptious chicken dinner. For context, this torus is thought to be the size of our entire solar system.

“We’re looking somewhere on the edge of that donut. We’re seeing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping over the surface that’s being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour,” Maksym said, which translates to 3 percent the speed of light.

Not only is this huge because, well, it’s absolutely spectacular — but also because galaxies with quiet, or quiescent, black holes like the one Hubble analyzed are expected to devour a star only once every 100,000 years.

“We really are still getting our heads around the event,” Maksym said.

A simulation of a star being ripped to shreds after it approaches a black hole.

DESY, Science Communication Lab

But it didn’t look like a Hollywood movie

To be clear, Hubble didn’t literally capture footage of everything happening in real time. So no, this black hole didn’t look like the iconic Interstellar leviathan from the ‘scope’s vantage point.

I mean, after all, this whole situation occurred some 300 million light-years away from Earth — which also means it happened about 300 million years ago, yet light from the event just reached our planet so we’re seeing it in what we call “the present.”

However, what Hubble did to catch this scene pretty much allows scientists to deduce what it would look like if we could somehow watch the details unfold like a film.

The telescope’s powerful ultraviolet sensitivity was able to study light borne from the shredded star that traveled to Earth over millennia, and astronomers could basically trace all those light signals to draw out how the star contorted, crumpled and creased as it perished.

You can watch an imagining of the event below, per the team’s calculations.

“There are still very few tidal events that are observed in ultraviolet light given the observing time. This is really unfortunate because there’s a lot of information that you can get from the ultraviolet spectra,” Emily Engelthaler of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, said in a statement. “We’re excited because we can get these details about what the debris is doing. The tidal event can tell us a lot about a black hole.”

This event, formally dubbed AT2022dsb, was caught on March 1, 2022, by a network of ground-based telescopes called the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae.

That piqued the interest of Hubble astronomers, who immediately moved to try to get some ultraviolet readings on the violent tidal disruption for as long as possible, to pin down as much information as possible of the star’s evolution as it grew ripped apart by the black hole.

“You shred the star and then it’s got this material that’s making its way into the black hole. And so you’ve got models where you think you know what is going on, and then you’ve got what you actually see,” Maksym said. “This is an exciting place for scientists to be: right at the interface of the known and the unknown.”