CNN

—

The young man smiling in the last Bakersfield High School student newspaper for the 1983 school year was captioned – “Most Likely to Succeed.”

That graduating student wasn’t then-senior Kevin McCarthy, the California Republican who on Saturday became the House speaker for the 118th US Congress, a powerful position that puts him second in line to the American presidency.

“I was most likely to succeed,” laughs Marshall Dillard, McCarthy’s classmate and friend. “I’m sure he’s surprised some of his teachers. You’d have never thought this if you saw Kevin in high school.”

The lighthearted teasing traces back to Dillard and McCarthy on the high school football field in Bakersfield, California. The team was and is still called “The Drillers,” a reference to the oil industry of the district. Bakersfield sits in the southern end of California’s Central Valley and is one of the largest cities in the state’s 20th Congressional District.

It’s the district McCarthy represents as one of the most powerful Republican lawmakers in the country. With House Republicans holding a slim majority in the 118th Congress, a group of GOP hard-liners prompted a messy and historic floor fight for control of the speaker’s gavel. After voting had spilled into a fifth day, McCarthy broke through by conceding to a series of demands that weakened the power of the speakership. But ultimately, he won the gavel.

This was the sort of well-worn political knuckle fight of the DC scene – but far from the region that raised a young Kevin McCarthy.

Here, he’s known as the son of a firefighter whose less-than-stellar grades would suggest a far less powerful career path. But like the working town that raised him, the lack of polish would impart lessons that follow McCarthy today and offer clues into his speakership.

“He made up for it because he was scrappy, and he worked hard,” says Dillard. “In football, he wasn’t the biggest person. He wasn’t the fastest person. He wasn’t the strongest person. But he was going to give it his all.”

Rather than being seen by classmates as most likely to succeed, McCarthy was voted one half of Bakersfield High’s “Best Couple.” His girlfriend, Judy, would become his wife.

“Before he was going to ask her out, that’s the only time I saw him nervous,” remembers Dillard. The rest of the time, McCarthy charged into classes, sports or clubs with an ambition that eclipsed his apparent credentials.

Fellow students gravitated to McCarthy, not just for his humor and confidence, but for his friendship.

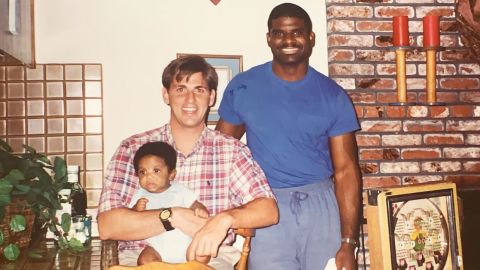

Dillard, now the principal of William Penn Elementary in Bakersfield, says a single moment from their teenage years speaks to the man who now leads the US House of Representatives. Dillard, who is Black, was the star player on the Bakersfield High School football team. He recalls a time when their high school was scheduled to play against a team from a notoriously racist rival high school. McCarthy and a couple of other White football teammates reassured Dillard, “They’re going to have to come through us before they get to you.”

“That cemented our bond,” says Dillard. The men have remained friends through the years, sharing their struggles, successes and tales of parenthood. Dillard declined to share his political leanings or say if he even agrees with McCarthy’s politics: “He always gets my vote. Politics is politics. They do what they do. I know Kevin on a personal level.”

On the 1983 yearbook’s local business sponsorship pages, “McCarthy’s Frozen Yogurt” takes up half a page. McCarthy has spoken about the yogurt shop belonging to his uncle and the place where he opened his first small business, “Kevin O’s Deli.”

In pictures: House Speaker Kevin McCarthy

Dillard, who would attend Stanford University, remembers Kevin O’s as a couple of tables in the corner of the yogurt shop. When Dillard would return home on school breaks, his friend always gave him a free sandwich.

Catherine Fanucchi, a farmer in Bakersfield, also grew up with McCarthy and calls him a friend today. She, like Dillard, left the Central Valley for school and a career – hers was as a lawyer. But home beckoned, and she joined her family farm, which traces its Bakersfield origins 100 years back.

“I would never see him staying down,” Fanucchi says of McCarthy. “He’s not that guy. He sees the sunny side of the street, and he’ll manage to find it.”

McCarthy would not stay at that sandwich shop long, sending in an application while he was in college to be a 1987 summer intern in Washington with then-Rep. Bill Thomas, a Republican from California.

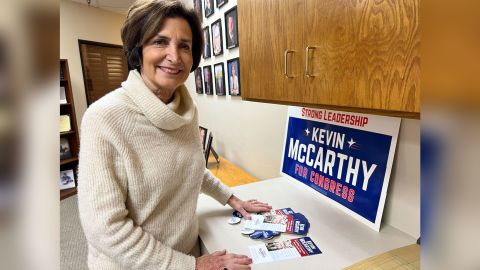

His application came across the desk of Thomas’ chief of staff, Cathy Abernathy.

“He didn’t make the cut for summer,” recalls Abernathy, who would hire him for the fall in the Bakersfield district field office. “He will mention in speeches often: ‘I’m the congressman from the district that turned me down to be an intern.’ It’s a true story.”

McCarthy became Thomas’ protégé, learning about constituent work and then the politics of Sacramento and Washington. Ambition and an ability to engage with nearly everyone separated him from others.

“Well, he’s probably the best homegrown candidate for public office that we have. Born and raised, then community college, college, and his masters’ degree – all from here,” says Abernathy, who remains a longtime ally. They have a symbiotic political, yet deeply personal, relationship. She recalls how just months after her husband died, McCarthy officiated her daughter’s wedding, offering counsel and solace to the family.

“He’s in a bigger job, but he hasn’t forgotten small town America.”

Thomas left Congress in 2007 and was succeeded by McCarthy. In the December 26 issue of The New Yorker, Thomas blasted his former protégé, saying, “Kevin basically is whatever you want him to be. He lies. He’ll change the lie, if necessary.”

“The Kevin McCarthy who is now, at this time, in the House, isn’t the Kevin McCarthy I worked with,” Thomas was quoted as saying.

The criticism came on top of Thomas’ first harsh public comments about his former staffer and friend shortly after the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the US Capitol. Thomas gave an interview to a local TV station accusing McCarthy of rolling over for Donald Trump and his election lies for political expediency.

McCarthy declined to speak with CNN for this story.

McCarthy did condemn Trump soon after the attack on the Capitol, saying, “The president bears responsibility for Wednesday’s attack on Congress by mob rioters.”

But not long after, McCarthy made a stunning reversal, saying, “I don’t believe he (Trump) provoked if you listened to what he said at the rally.”

Since then, McCarthy has catered to some of his party’s contentious members, vowing to reinstate Reps. Paul Gosar of Arizona and Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia on committees if Republicans won back the House.

And despite the back-and-forth on Trump, the former president supported McCarthy’s run for speaker and made calls on his behalf for the holdout votes. Trump has publicly referred to McCarthy as “My Kevin.”

The political malleability is familiar to Bakersfield conservative Paul Stine. The men have known each other since 1995, battling when they were young Republicans. “Kevin is the most adaptable politician I have ever seen in my life,” says Stine.

When they were younger, Stine viewed McCarthy as too centrist, like Thomas and Arnold Schwarzenegger.

“If the Kevin of today had been the Kevin of the 1990s, I doubt he and I would have ever had an adversarial relationship. I think he knows how to evolve his positions enough to stay viable in the political game. Do I consider him a conservative ideologue? No, not at all,” Stine says.

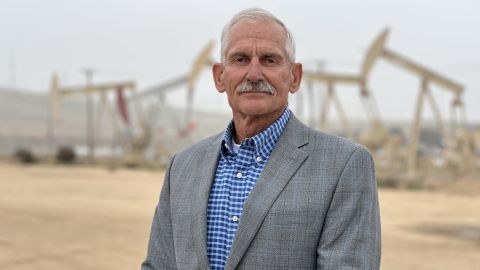

Dave Noerr, the mayor of Taft, a city in McCarthy’s district, brushes off the criticism, calling it a part of today’s politics. Noerr, who has worked with McCarthy since the early 2000s, calls him “unique and thorough in understanding energy and agriculture.”

Noerr has worked in and around the oil industry for most of his life. His town and the entire district relies on the energy industry for jobs and money but is seeing a rapid evolution as oil production gets slammed.

“By Kevin McCarthy coming from this area, understanding the need and the opportunity to integrate all those resources for the betterment of mankind, that is going to be critical to getting rid of the fantasies being peddled of some and the misunderstanding of so many,” says Noerr.

Fanucchi, the Bakersfield farmer, declines to express her politics and state whether she agrees with McCarthy’s positions. More important to her is having a powerful representative in Washington who understands the challenges of feeding the nation in today’s economy.

“He comes from here,” Fanucchi says of McCarthy. “We have direct access to him, and he has access to people to help us tell our story. Our story is that the lifeblood of the Central Valley, of California, is Ag, which requires water and requires space. I don’t ascribe to the belief that you have to be like me to think like me, to do something great for us in Kern County or for our nation. I think you have to have clear eyes and a strong mind and work hard.”

A Republican, Noerr has hopes that the slim majority his party now holds in the House will be a blessing to help his district, rather than a challenge.

“The deep rifts that currently exist and unfortunately have been exacerbated recently, he’s (McCarthy) got to get rid of. We can find the common ground,” Noerr says. “Instead of having arguments, we have conversations. We will find that common ground. Do I think he can do that? Absolutely, I think he can.”