CNN

—

He was a former Republican president with a mammoth ego, a sense of entitlement and simmering resentments. Critics called him mentally unstable and a racist, and some even noted his small hands.

We’re talking, of course, about one of America’s greatest presidents — Theodore Roosevelt.

There’s been a lot of commentary recently about the legendarily tough Roosevelt, who once insisted on giving a nearly 90-minute speech moments after being shot in the chest by a would-be assassin. After former President Trump recently announced plans to run for the White House in 2024, some pundits said he could provoke a schism within the GOP that could hand the presidency to the Democrats—the same scenario that Roosevelt triggered in 1912.

Roosevelt precipitated this GOP doomsday scenario when, almost four years after leaving the White House, he challenged his party’s presidential nominee in 1912, William Howard Taft. Roosevelt tagged the portly Taft with insulting nicknames such as “Fathead,” “Puzzlewit” and “Flubdub.” When he failed to secure the GOP presidential nomination, he claimed the party’s nominating process was corrupt.

He then formed a third party to run in the general election, which split the GOP base, handing the election to the Democratic presidential candidate, Woodrow Wilson.

“The parallels to 1912 for the Republicans are striking and terrifying,” says Jerald Podair, a historian at Lawrence University in Wisconsin. “There was very little the GOP could do institutionally in 1912 to prevent this debacle. Roosevelt was determined to become president again and held a substantial portion of his party in thrall. So there was no compromise possible, no middle-ground face-saving to save the day.

“1912 is not so much a warning to the Republican Party in 2024 as it is an ominous prediction.”

But look deeper, and you’ll find at least three other ominous parallels between Roosevelt and Trump. They reveal that the line between a great and failed president is much thinner than most people realize.

Comparing Roosevelt with Trump may seem at first like historical blasphemy.

Sure, there are some superficial similarities. Both were born into moneyed New York families, both had wealthy, demanding fathers who profoundly shaped them, and both took on the political establishment of their era.

But Roosevelt was a progressive who battled corporate monopolies, disdained the idle rich and had a genuine compassion for the poor. He championed many reforms — a living wage, a social safety net that included workmen’s compensation, pensions for the elderly — adding up to what he called a “Square Deal” for the less fortunate.

Trump’s signature policy victory during his only term in office was the passage of a tax cut that largely benefited corporations and the wealthy.

Roosevelt’s physical courage was also unquestioned. Before he became president, he once knocked out a gun-toting, drunken cowboy who accosted him in a bar. And he led a regiment of calvary volunteers, known as the Rough Riders, on a famous charge during the Spanish American War in 1898.

President Trump has said his heel spurs earned him a medical deferment which kept him out of the Vietnam War.

Roosevelt had a formidable intellect. He spoke both French and German and authored an estimated 35 books, ranging from assorted biographies and tomes on hunting and nature to a well-regarded analysis of naval warfare.

Trump mused during a 2020 White House briefing about whether disinfectants such as bleach could treat the coronavirus in humans, asking if there is “a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning.”

Roosevelt was “a rabid reader of books and learner of things,” says David Gessner, author of “Leave It as It Is: A Journey Through Theodore Roosevelt’s American Wilderness.”

“Roosevelt had a curiosity, an empathy and an interest in the world beyond himself, whether that was other people—he was a surprisingly great listener—or the natural world,” Gessner says.

But Gessner also believes Roosevelt and Trump shared at least one dominant trait: “raw egotism.”

Trump’s need for constant ego stroking is well documented. Despite contrary photographic evidence, he claimed he had attracted the largest audience to ever witness an inauguration. A bogus 2009 Time magazine cover with an all-caps headline, “TRUMP IS HITTING ON ALL FRONTS … EVEN TV,” once hung in at least five of his country clubs. And during a 2017 NATO gathering, Trump shoved other foreign leaders out of the way so he could be photographed at the head of the group.

But Roosevelt’s ego was also as big as his carving on Mount Rushmore, scholars say.

The Pulitzer-Prize winning historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote in her book, “Leadership in Turbulent Times,” that Roosevelt craved the spotlight “as a plant craves sunshine.”

Roosevelt’s daughter, Alice, once said of her father: “He wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening.”

A healthy ego is not necessarily bad for a president. It took enormous self-confidence for a relatively inexperienced senator with a funny name to think he could become the nation’s first Black president.

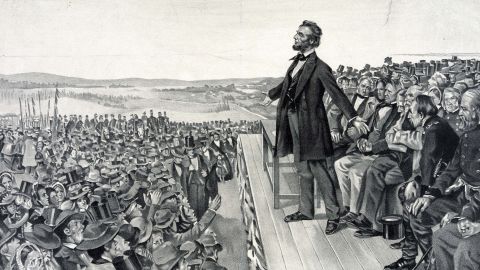

Or consider Abraham Lincoln. Historians love to talk about his humility, but it took tremendous self-belief to redefine the meaning and purpose of America in 272 words—something Lincoln did with his majestic “Gettysburg Address.”

But Roosevelt’s ego marred his political judgment. He despised Woodrow Wilson, the president who succeeded him, even though Wilson pushed through many of the progressive policies Roosevelt was unable to pass, says Podair, the Lawrence University historian.

“Roosevelt was resentful of anyone who would steal the spotlight from him,” Podair says. “He was openly jealous and resentful of Wilson, though he really didn’t disagree with Wilson about very much except whether the United States should enter World War I. He had nothing but disrespect for Wilson, and it wasn’t because of anything personal about Wilson. It was the fact the Wilson was president, and he was not.”

Love or loathe him, there has never been a president like Trump.

No other president was a reality TV star, once slammed an opponent to the floor at a pro wrestling event, or boasted about the size of his penis during a debate. He erased the line between entertainment and presidential politics in a way that had not been done before.

With his use of Twitter, Trump also mastered a way to speak directly to his supporters and enemies – and to spread disinformation – without interference from the media.

Trump’s ability to command media attention is unparalleled among contemporary presidents. He generated constant headlines with a seemingly never-ending parade of lies, outrageous statements and racist tweets.

Roosevelt also commanded attention in an unprecedented way when he assumed the presidency in 1901 after the assassination of President William McKinley. At 42, he was the youngest American president at the time, bursting into the Oval Office like a human tornado with his perpetual grin and nonstop motor.

“He was a completely outsized political character, the likes which had never been seen in Americans politics,’ says Podair. “He is the Donald Trump of his day.”

Before Roosevelt, most presidents resembled political fossils—stolid, sober figures stuck in the tar pits of tradition. Congress largely dominated national politics in the 1800s, and political machines typically decided who was going to occupy the White House. But Roosevelt is credited with making the president the center of American political life. He is considered the first modern president.

How did he do it? Through sheer exuberance, audacity and a clever sense of public relations.

Watch Donald Trump announce his 2024 candidacy

Americans were fascinated by a president who skinny-dipped in the Potomac River, sparred with boxers in the White House (one match even left him partially blinded), and dragged cabinet member on rugged hikes in Washington’s Rock Creek Park. In his spare time, he transformed the US Navy into an imperial juggernaut dubbed the “Great White Fleet,” took on Big Business to protect the average American and won a Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating an end to the Russian-Japanese War in 1905.

The core of Roosevelt’s approach to life and government was what he called “the strenuous life” of being “The Man in the Arena.”

He once said: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without errors and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds…”

Roosevelt showed much of that same vigor in courting the press. Like Trump, he was a pioneer in using the media to increase the power of the presidency.

He was the first president to initiate the building of a press office in the White House; the first to make an official appearance in an automobile; and the first to travel abroad on official business. He even took journalists and photographers with him on hunting trips.

Before there was the Trump reality show, there was the Teddy reality show.

“He’s our first celebrity president, our first modern media president,” Podair says. “He was a reality show unto himself.”

Yet some of the same qualities that make a president great are the same traits that make them awful ex-presidents, historians say.

Start with how they handle power. The Oval Office attracts people who are drawn to power. Presidents can set the national agenda, start wars and become mythical figures if they possess enough personal charisma.

But power can also be addictive. Some ex-presidents become depressed with the sudden loss of power and attention. Though he was never president, former Secretary of State James Baker captured this surreal shift faced by ex-presidents when he once said, “You know you’re out of power when your limousine is yellow and your driver speaks Farsi.”

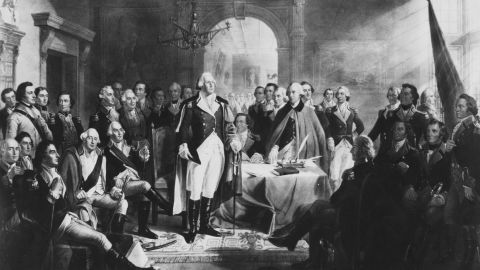

George Washington is consistently rated as one of our greatest presidents in part because of how he stepped away from the spotlight. As the first American president, some historians say he could have stayed in office and become a virtual king. Yet he limited his time in office to two terms and retired to Mount Vernon.

Washington is often compared to Cincinnatus, the Roman statesman who was called out of retirement and given unlimited authority to defend Rome against foreign invaders but relinquished his power after Rome won and returned to his farm.

Roosevelt, though, wasn’t the type to take up a plow. He didn’t adjust well to such a loss. He felt entitled to be president again because all the other presidential candidates were weaklings compared to him, Podair says.

“We’re talking about a self-aggrandizing, very egotistical— an effective president, no question about it—but someone who had the idea that many presidential level politicians have: that only he can save the country,” Podair says.

Roosevelt failed in his second bid to capture the White House in the 1912 presidential election. By then the country had moved on. Roosevelt, though, didn’t know how to do the same.

“He went back to Oyster Bay in Long Island and sank into depression,” says Gessner. “He couldn’t really handle not being in the public eye. He wasn’t built for it.”

Gessner says the same is true for many other ex-presidents, adding that presidents who weren’t known for their huge egos tended to adjust best to life outside of the Oval Office.

“You could argue that our most successful ex-president is one of our most humble, and that’s Jimmy Carter,” Gessner says, citing Carter’s charitable work, peacekeeping missions and successful efforts to eradicate a tropical disease. “Ego is necessary to become a president and do things and get things done. But it can hurt people when they’re out of power.”

Roosevelt eventually recovered from his failed presidential bid by embracing another journey. He embarked on a dangerous expedition through the Brazilian jungle to navigate an unmapped river in the Amazon.

He faced deadly rapids, alligators and piranhas. At one point his party almost starved, and one man murdered another over food.

Roosevelt, then in his 50s, barely survived the trip. He called it his “last chance to be a boy.” He never quite recovered from the ordeal and died in his sleep in 1919, at the age of 60.

“Death had to take him sleeping,” Vice President Thomas Marshall said at the time. “For if Roosevelt had been awake, there would have been a fight.”

Trump is not navigating the Amazon, yet he faces treacherous political and legal waters as he attempts to retake the White House. He is still refusing to accept the result of the 2020 election. Much of his recent 2024 campaign announcement focused on restoring him, an aggrieved party, to the Oval Office. Like Roosevelt, he’s given his main GOP rival, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a pejorative nickname.

So will Trump’s 2024 journey end in triumph, or failure? If he fails, his inability to leave the arena could split the GOP and hand the presidency to a Democrat.

Roosevelt did just that in 1912, but he is still considered one of America’s greatest presidents because of his other accomplishments.

If Trump’s third quest for the White House fails, the verdict from history may not be so kind.