In 2005, the year I moved to New York City, the NYPD recorded 135,475 crimes in the seven “major felony” categories — homicides, assaults, rapes, and various forms of theft. The next year, that number dropped, and it kept dropping. By 2017, it was around 96,000, where it stayed until last year, when it snuck back over 100,000, mostly due to an increase in grand larcenies, auto and otherwise. The “non-major” felony data has followed a similar arc, dropping almost 30 percent since 2005. By the official crime numbers, the most dangerous year that I’ve lived in New York City was the first one — by a lot.

So why do people keep asking me if I’m safe here? Last week, I found myself assuring a kind older gentleman in town from Boston — where violent crime has been creeping up after pandemic lows — that he was almost certainly perfectly fine walking around the swanky restaurant-laden blocks near Times Square. Statistically, the Big Apple is safer than small-town America, and its per-capita murder rate was at the bottom of the list of big cities in early 2022. I’ve been intrigued and baffled hearing from people from my hometown (which leads upstate New York in crime statistics) who might have taken a day trip down to the city to see the Christmas decorations and eat some roasted chestnuts, but won’t travel here anymore because they think it’s a war zone.

Emotional stories speak louder than facts, perhaps especially in a city as storied as New York. Writing of the city’s crime narratives during a much more dangerous era, Joan Didion wrote of observers’ “preference for broad strokes, for the distortion and flattening of character and the reduction of events to narrative” — in other words, the nearly universal desire to make stories out of feelings, and then believe them. And when people ask me if “New York is safe,” they don’t want to know about numbers. They’re asking about feelings.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24219582/1242290505.jpg)

How people perceive crime, and how politicians represent it to the electorate, has less to do with data and more to do with vibes. In October, while fact-checking the claims of rising violent crime that drove many midterm campaigns, the Pew Research Center’s John Gramlich noted that “the public often tends to believe that crime is up, even when the data shows it is down.” Data from the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics shows that there’s no increase in violent crime across the board in the US, and yet for most years in the last three decades, the majority of America adults thought there was more crime nationally than the year before, even though the opposite was true. Indeed, over three-quarters of those polled in October by Politico/Morning Consult said they thought violent crime was rising nationally and 88 percent said it was increasing or remaining the same in their own communities.

It’s not just ordinary citizens whose perceptions about crime in specific places can be markedly divorced from reality. In 1990, there were 2,262 murders in New York, and Mayor Eric Adams was a transit officer. But in May 2022, he claimed he’d “never witnessed crime at this level,” even though the murder total in 2021 was 488, a little less than a fifth of the 1990 level. (Per the NYPD’s own data, the rate of crime is more than 80 percent lower than in 1990.) Adams has alternated between saying he’s afraid to take the subway and taking credit for the city’s continued drops in violent crime. It’s hard to know what to believe, maybe even for Adams.

News coverage, which seizes on the stories that seem most emblematic of the problems the viewers and readers fear, has a profound effect on how people perceive criminal justice and their own safety. Furthermore, popular entertainment has seized upon crime as the most hardy and enduring way to draw in an audience, whether it’s the endless true crime documentary machine, the Lifetime movie engine, or the Law & Order empire. A steady diet of crime content magnifies our sense that crime happens at random all the time and that we’re the next target.

So even if the facts tell us that New York City, or maybe our hometown, is a safe place to live, that we’re highly unlikely to be the victim of a crime, and that within most of our lifetimes there’s been a marked change for the better, we still find ourselves living another story.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24219595/1438801.jpg)

And that’s a dangerous place to be, something Didion detected so clearly in the city’s storytelling. “The imposition of a sentimental, or false, narrative on the disparate and often random experience that constitutes the life of a city or a country means, necessarily, that much of what happens in that city or country will be rendered merely illustrative, a series of set pieces, or performance opportunities,” she wrote in 1991, at a time when crime was truly, statistically skyrocketing. In her essay “Sentimental Journeys,” about the 1989 assault of a jogger in Central Park that led to the wrongful conviction of five teenagers from Harlem, she explored how that particular crime became a symbol of everything that was wrong with New York and, by extension, the country at large. Women had been assaulted and murdered in other contexts throughout the city, but the Central Park jogger case caught the imagination of the world primed to see it as illustrative of whatever they believed was wrong with humanity.

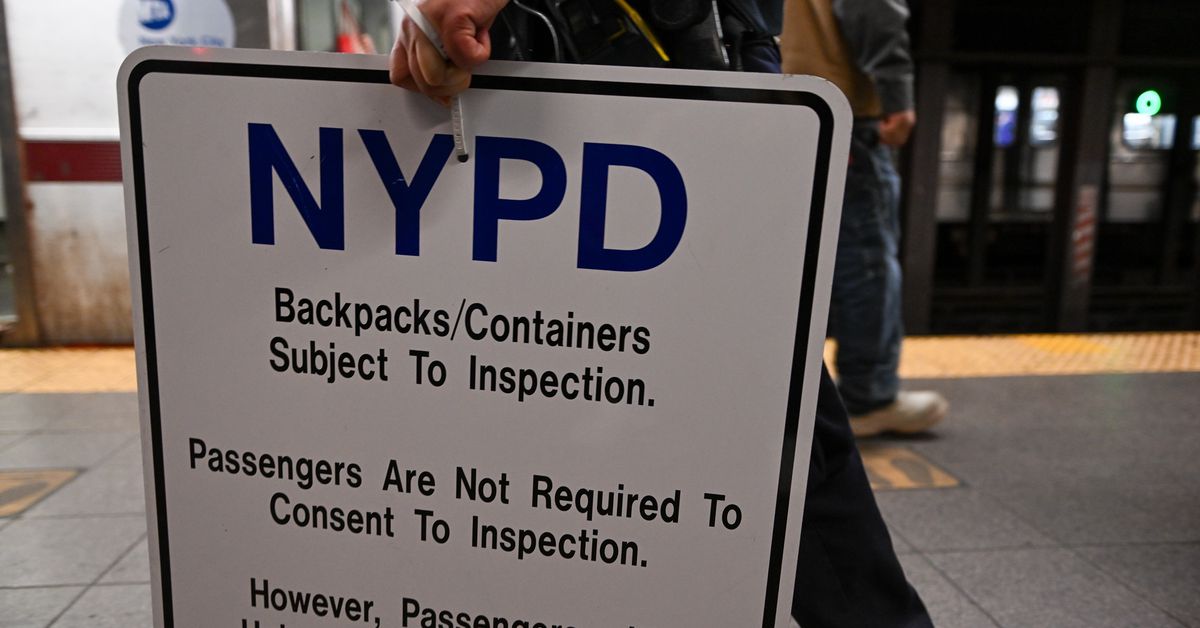

And so, while an actual woman was harmed, and five young men had decades of their lives taken from them by the state, politicians found a place to land their lofty rhetoric. Didion notes that “Governor [Mario] Cuomo could ‘declare war on crime’ by calling for five thousand additional police; Mayor Dinkins could ‘up the ante’ by calling for sixty-five hundred.” As if they’re crusaders in Gotham working with Batman to rid the town of crime, not public servants making decisions based on careful analysis. All these years later, history repeated: New York Gov. Kathy Hochul announced in September that cameras would be installed on 2,700 subway cars to “focus on getting that sense of security back” — a telling focus on feelings. At the same press conference, Adams said that “if New Yorkers don’t feel safe, we are failing.” Recently, subway conductors have begun announcing at nearly every stop that NYPD officers are on the platform “in case you are in need of assistance,” apparently as part of the police surge announced by Adams and Hochul.

Even if you buy that there’s a causal link between police presence and safety for subway riders, the new surge is cold comfort to those who actually ride the subways every day. An already beefed-up NYPD presence in and around subways has been obvious for well over a year; they were the only group of people who seemed to be able to walk around the transit system unmasked without fear of being fined. Cross through the busy Atlantic Avenue station in Brooklyn at 11 pm on a Thursday, and you’ll see clumps of three or four cops everywhere, chatting with one another as the traffic flows around them.

At the same time, there’s been a rise in killing in and around the subway (nine this year, rather than the pre-pandemic average of two per year; last Monday 3.5 million rode the subway in one day). When, in January, 44-year-old Michelle Go was pushed onto the tracks by a mentally ill man and killed, there were six cops in the station, and two nearby.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24219619/1240915765.jpg)

And when there was an actual shooting in the subway last spring (thankfully resulting in no fatalities), the suspect remained at large for a day, with police unable to find him even though he left a credit card at the scene of the crime. Adams said one of the cameras in the station wasn’t functioning, as well as cameras in the stations before and after. The suspect was finally apprehended — by a civilian.

The point of all of this is that the narrative seems wrong, and that means the conclusion is off. The narrative goes like this: Crime is happening, and it feels like it’s happening more now than ever because people keep saying it is — even the mayor! Police deal with crime, and thus, we need more police, and they will stop the crime from happening. It is sentimental because it taps into feelings we have, and those feelings just seem like they’re true. But there are basic contradictions in the story. So continuing to tell it becomes a way of comforting ourselves, and also of increasing police budgets.

Yet the story doesn’t answer basic questions we ought to be asking: Why did that crime happen in the first place? What root problems does it illuminate, and how can those be solved? If the issue is, as Adams says, that there are many mentally ill people in the subways who commit crimes, are they New Yorkers who deserve a sense of protection and safety too? Does history show that increased police presence aids these people?

Or does “New Yorker” only refer to people like me?

The sentimental narrative simplifies the reality of the “disparate and often random experiences” of life and provides “performance opportunities.” The situation “offered a narrative for the city’s distress, a frame in which actual social and economic forces wrenching the city could be personalized and ultimately obscured,” wrote Didion. Cases like that of the Central Park jogger were a way for the city to deal with its general anxiety about the widening economic and social gap, something that had become stark during the 1980s, with the same solutions being suggested:

Here was a case that gave this middle class a way to transfer and express what had clearly become a growing and previously inadmissible rage with the city’s disorder, with the entire range of ills and uneasy guilts that came to mind in a city where entire families slept in the discarded boxes in which new Sub-Zero refrigerators were delivered, at twenty-six hundred per, to more affluent families …

If the city’s problems could be seen as deliberate disruptions of a naturally cohesive and harmonious community, a community in which, undisrupted, “contrasts” generated a perhaps dangerous but vital “energy,” then those problems were tractable, and could be addressed, like “crime,” by the call for “better leadership.”

That’s what I think about now when I listen to people tell me how dangerous New York is, or listen to the mayor give solutions — well, the same solution, over and over. The facts, and the problems, don’t match the “solutions”; they’re the conclusion to a story that lies on top of reality. It’s not that there’s nothing to worry about. It’s that, on the whole, we rush to the fix that assuages our fears, rather than hunting around for new ones. Or we change behaviors in order to protect ourselves from things that pose a very small threat, which gives us the emotional permission to ignore the much larger one we pose ourselves.