This story is part of Choosing Earth, a series that chronicles the impact of climate change and explores what’s being done about the problem.

If you’re reading this article on a phone (or a tablet or laptop), between your hands you’re clutching important pieces of the Earth’s crust, which have been dug up from mines around the world.

The iPhone for instance, contains an estimated 30 chemical elements, spanning well-known metals like aluminum, copper, lithium, silver and, yes, even gold. But that’s just the start. There’s also an array of obscure metals known as rare earth elements, prized for their wide-ranging tech and renewable energy applications, tucked away inside your iPhone.

Many people around the world use rare earth elements, or REE, every day — without even knowing it since they’re hidden in common personal electronics. If you use an iPhone, an REE called lanthanum helps make sure the screen has a vivid color pop, while neodymium and dysprosium are credited for helping the device vibrate, among other uses. In electric cars, magnets, which are used to help power the vehicle, rely heavily on rare earths such as neodymium.

Mark Hobbs/CNET

But experts warn that the critical metals required to make your smartphones, among other electronic products, are at risk of a shortage as the world transitions to a greener economy. A shortfall of these irreplaceable metals, which are a key piece of the puzzle in accelerating the green shift, could derail climate goals of keeping global temperatures from rising 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels by 2100, a critical turning point for the damage that global warming is wreaking on our planet.

Researchers have sounded the alarm bell over smartphones for contributing to the depletion of elements, even though they’re found in a whole range of electronic products.

“We focused on the smartphone because almost everyone has one and they create major problems leading to waste and element depletion.” said David Cole-Hamilton, vice president of EuChemS and emeritus professor of chemistry at the University of St. Andrews.

A 2022 European Chemical Society statement said the unsustainable usage of seven elements in smartphones (carbon, yttrium, gallium, arsenic, silver, indium and tantalum) will pose a serious threat of depletion in the next 100 years.

“It is astonishing that everything in the world is made from just 90 building blocks, the 90 naturally occurring chemical elements,” Cole-Hamilton said in an earlier statement.

The high carbon cost of phone production

Despite the unsustainable supply of raw materials, lots of iPhones are sold every day — and the allure of Apple’s iconic product isn’t diminishing by any means. The iPhone just had its most successful September quarter ever, generating $42.6 billion in revenue, or nearly half of Apple’s overall quarterly revenue of $90.1 billion.

Those robust sales came despite each of Apple’s recent phone lineups, the iPhone 14 and iPhone 13, receiving minimal technical upgrades. According to CNET Managing Editor Patrick Holland, the iPhone 14 represents “one of the most minimal year-over-year upgrades in Apple’s history.” However, those sales figures could also have been boosted by people simply upgrading older models.

Whatever the reason, environmentalists question the need for upgrading smartphones every year given the environmental cost, which includes the polluting extraction of vulnerable raw materials as well as the associated carbon emissions released into the atmosphere.

Read more: Getting a new iPhone every 2 years is making less sense than ever

Long before iPhones roll off the assembly lines in Zhengzhou, minerals are pulled from the earth from around the globe, the very first step in an iPhone’s life. This is the US’s only rare-earth mineral mine. It’s located in Mountain Pass, Calif., and was run by Molycorp before it filed for bankruptcy in 2015.

Jay Greene/CNET

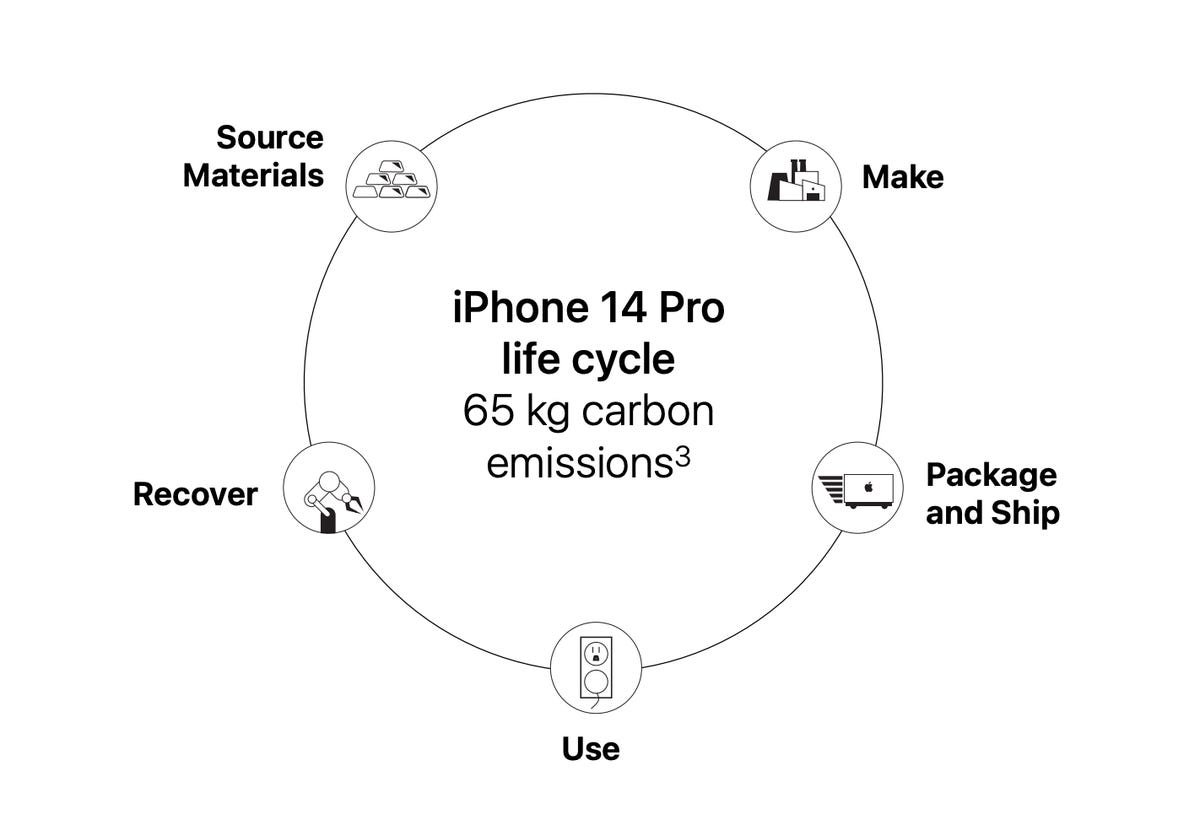

A typical smartphone generates most of its carbon emissions at the beginning of its lifecycle: the manufacturing stage. Take the iPhone 14 Pro, for example. Apple says it emits 65 to 116 kilograms of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during the lifecycle of iPhone produced. Out of that, 81% or 53 to 94 kg of carbon dioxide is emitted during the production process, which Apple says includes extraction, production and transportation of raw materials, as well as the manufacturing, transport and assembly of all parts and product packaging.

This means the manufacturing process is the most carbon intensive phase of the iPhone’s lifecycle, dwarfing carbon dioxide emitted in the remaining phases: use, transport and end of life, although their environmental impact is still significant.

This isn’t unique to just the iPhone. Google’s flagship Pixel 7 phone produces roughly 84% of carbon emissions per phone at the manufacturing stage of its lifecycle. As environmental advocacy group Greenpeace points out, “various life analyses find the manufacturing of devices is by far the most carbon intensive phase of smartphones.”

“Because manufacturing accounts for almost all of a smartphone’s carbon footprint, the single biggest factor that could reduce a smartphone’s carbon footprint is to extend its expected lifetime,” Deloitte wrote in a 2021 report.

The iPhone 14 Pro’s estimated carbon footprint for its entire lifecycle.

Apple/Screenshot by Sareena Dayaram

Rare earth minerals: Technically abundant, effectively rare

With names like dysprosium, neodymium and praseodymium, rare earth elements aren’t exactly household names. But the products they’re used in — including iPhones and Tesla cars — certainly are.

In smartphones, REEs tend to comprise only a fraction of the device’s mass, yet rare earths mining is a massive and lucrative global business. That’s partly because of the global ubiquity of high-tech devices like smartphones, which require the minerals’ conductive and magnetic properties to help them function at the cutting-edge. Statista estimates the number of smartphone subscriptions globally have exceeded 6 billion, and that number is projected to rise by several hundred million in the coming years.

Perhaps the most important use for the rare earth metal neodymium is in an alloy with iron used to make very strong permanent magnets. This makes it possible to miniaturize many electronic devices, including mobile phones, microphones, loudspeakers and electronic musical instruments. It is also used in electric vehicles and wind turbines.

Ames Laboratory

While REE’s are critical to the survival of smartphone makers, the importance of these minerals extends far beyond the borders of tech hubs like San Francisco, South Korea and mainland China.

According to a 2021 report by the International Energy Agency, the world will be unable to combat the climate crisis unless there is a drastic increase in the supply of rare earths as well as other so-called “green metals” (like lithium, copper, and cobalt). These metals, used in smartphones and other consumer electronics, are vital to technologies that are expected to play a key role in tackling the climate crisis like electric vehicles, wind turbines, and other items needed for a clean energy transition. Demand for these elements are surging as countries around the world transition to green energy to help hit climate goals, the report says.

“Lithium and rare earths will soon be more important than oil and gas,” Thierry Breton, European commissioner for internal market, wrote in a September LinkedIn post.

REE’s are more naturally abundant than their name suggests, but extracting, processing and refining the metals into a usable form poses a range of environmental issues. China, which produces the vast majority of the world’s REE supply, has suffered alarming environmental consequences including toxic contamination of water and soil.

Powder versions of such rare-earth minerals as Neodymium and Europium. It took a lot of work and processing to get it to this powdered state.

Jay Greene/CNET

Despite this range of issues, the majority of the materials used to make smartphones are not recycled at the end of a smartphone’s life, even with trade-in programs made by companies like Apple. By e-waste recycling, green metals used in consumer electronics such as phones can be recovered once products reach the end of their life, experts say.

“We propose that people should keep their phones for longer (reduce demand), have their phones repaired if something breaks (repair), give the phone to someone else if they have to get a new one (reuse) and hand then into a company that does ethical recycling once they really cannot be used any more (recycle),” Cole-Hamilton said.

“In this way, we can have a circular economy of phones.”