After Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017, artist Gabriella Báez’s life changed.

The island Báez knew didn’t exist anymore. Neither did the life. In the months following the storm, Báez’s father died by suicide — a death they in part attribute to the mismanagement of the emergency by both the local and federal government.

Báez turned to their camera to process their twofold grief: mourning both their father and their country. Alongside that of 19 other Puerto Rican artists, their work will now be part of a new exhibit at The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

It is the first scholarly exhibit focused solely on Puerto Rican art organized by a major U.S. museum in almost 50 years, according to the Whitney.

Making art to bear witness

Marcela Guerrero, the Jennifer Rubio Associate Curator at the museum, is the brain behind the exhibition. Guerrero, who is Puerto Rican, watched the storm unfold from New York, where she had just given birth. Many in the diaspora were glued to the news, she said, trying to do all they could to help; she immediately knew she wanted to use the hurricane as a focal point.

When you talk to people from Puerto Rico, she said, it’s BM and PM: “before Maria” and “post Maria.”

Armig Santos, Procesión en Vieques III, 2022. Credit: Courtesy Armig Santos

“There are certain events that mark histories and societies,” Guerrero said. “I think Maria was that moment in recent Puerto Rican history, arguably all of its history. I didn’t want to ignore that.”

Hence the title of the exhibit.

“That verse kind of brings up this idea of being perpetually caught in this wake of the hurricane,” Guerrero said. “Puerto Ricans are not afforded the luxury to think outside of the hurricane. Everything is a consequence of the disaster.”

Sofía Córdova, still from dawn_chorus ii: el niagara en bicicleta, 2018. Credit: Courtesy Sofía Córdova

After 2017, San Juan-based artist Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s perspective — on her work, and on her country — shifted.

She began experimenting with analog film, working with film moldy from humidity and coating rolls in salt in an attempt to corrode the images. Just as the storm and the environment destroyed parts of the country, she used the environment to destroy her art.

Her short film “Celaje” is featured in the Whitney’s exhibition, and juxtaposes her grandmother’s life story with that of Puerto Rico. In the 1960s, her grandmother moved to Levittown, then one of the largest planned communities in the country. At the time, Gallisá Muriente said, it was a brand new suburb of middle class homes, epitomizing the American dream of upward mobility.

A still from Sofía Gallisá Muriente’s film, “Celaje,” 2020. Credit: Courtesy Sofía Gallisá Muriente

But by 2019, when her grandmother died, the neighborhood had completely changed, Gallisá Muriente said — full of shuttered schools and houses that had been transformed into businesses. (Her grandmother’s house, meanwhile, was flooded when Maria hit.) And the disintegration of those slippery dreams of progress is shown literally in “Celaje,” through expired and decaying film.

Curating memories in a time of change

At home in New York, Guerrero remembered seeing an image of the archipelago completely dark, due to loss of power. It looked almost like the country had been erased from the map.

It felt, she said, like a perverse prophecy — Puerto Rico disappearing. And today, many Puerto Ricans are migrating away from the island, Guerrero said.

“The conditions of living are so impossible that the island almost feels like it’s being emptied,” she said.

Báez echoed those sentiments. With rising costs of living, material conditions on the island make it hard to stay, they said. It’s becoming an island for foreigners, not Puerto Ricans.

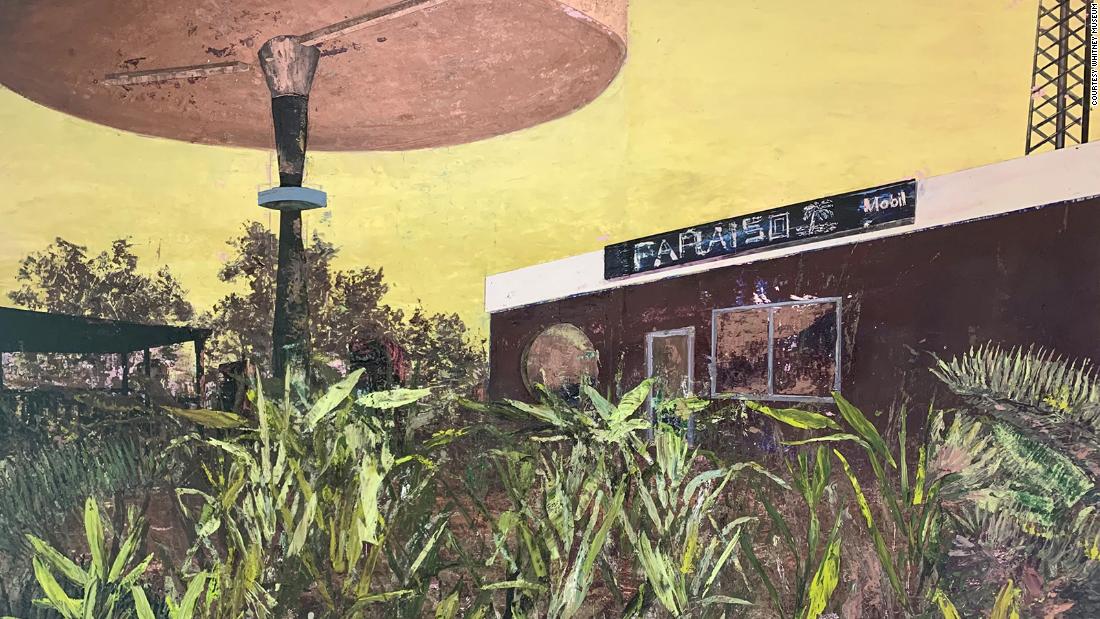

Gabriella Torres-Ferrer, Untitled (Valora tu mentira americana) (detail), 2018. Credit: Courtesy Gabriella Torres Ferrer

“By talking about Hurricane Maria, sure, I’m talking about a hurricane… but in the specific case of Puerto Rico, when you have such a strong, devastating, catastrophic natural event happen, but on top of that you add this colonial context, you get a society that is losing its people,” Guerrero said. “It’s this constant scene of death, even if it’s not literal, of mourning a Puerto Rico that’s no longer there.”

With this exhibition, artists are reflecting on the storm and its impact, Guerrero said, and affirming their existence through their work.

On display isn’t just art. It’s resistance.