NASA’s plan to return humans to the moon is officially one small step closer to reality with the launch of its most powerful rocket ever. During the dark and early hours of Wednesday morning — following a painstaking road to launch — the agency’s mammoth, tangerine Space Launch System finally flared to life, lifting off from Launch Complex 39B at Kennedy Space Center.

And it was brilliant.

“We are all part of something incredibly special,” launch director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson said just before getting her tie cut — a lovely NASA tradition that humbly marks the first solo flight of a deserving team member. “The first launch of Artemis. The first step in returning our country to the moon — and on Mars.”

Engineers and scientists at NASA mission control giddily embraced as the massive SLS rocket, with the Orion crew capsule at its crown, passed critical checkpoints, discarded its massive core stage just minutes into the flight and sent its snow-white spire off on an epic cosmic journey. You could almost feel the team’s anxiety turn to relief as this multi-billion dollar machine pierced through the atmosphere unscathed.

“I want you to look around at this team and know that you have earned it,” Blackwell-Thompson said to the mission control room post-launch. “You have earned a place in the room; you have earned this moment; you have earned a place in history.”

The historic launch of the Artemis I mission comes after years of delays, setbacks, doubts over viability and increasing costs. It, potentially, lays the groundwork for astronauts to place their boots in the sticky, gray lunar soil in the coming years — and perhaps, the red sands of Mars in the distant future. But, of course, there’s a long way to go before such sci-fi destinations fall within our reach.

Arriving at this special moment hasn’t been easy. It has actually been rather tumultuous, to say the least.

At first, NASA had hoped to see Artemis I kickstart its ambitious new moon program on Aug. 29, but that initial attempt was hampered by a leak in a line that feeds liquid hydrogen into the rocket’s monster booster. Then, a second attempt was called off on Sept. 3 due to engine issues, and then, just as the craft seemed ready to finally take off, Hurricane Ian rolled in and spoiled the fun. (Hurricane Nicole, which bore down on the Floridian coast last week, also spurred a tiny blip in the timeline).

But now, that’s all in the past.

Finally, just after 10:45 p.m. PT Tuesday (Nov. 16 1:45 a.m. ET), Artemis I’s lunar journey began. Liftoff, streamed across the world in glorious high definition, was a far cry from the grainy footage of Saturn V that crackled through old CRT TVs in the late ’60s — aka, NASA’s first dance with Earth’s glowing companion.

As the SLS punched through the sky, smoke and fire billowing from its impressive rocket engines, it discarded its side boosters and reached a speed of 17,430 miles per hour before main engine cut-off.

Such a departure from Earth, however, is just the beginning Artemis I’s month-long sojourn-slash-test-flight. At the end of it all, a pearly white Orion capsule will gain its stripes while traveling a total of 1.3 million miles, circling the moon for a week and returning to Earth faster and hotter than any spacecraft before it could’ve dreamed of. Various trajectory burns and orbital readjustments still remain on the spacecraft’s checklist — to be completed during the entire cosmic trek — and their execution will determine the ultimate fate of Artemis I.

In turn, that means they’ll also affect a flurry of future missions nestled into NASA’s extraterrestrial travel program.

For now, over the coming hours and days, the Artemis team will be watching to get their first real look at the meticulously built spacecraft’s systems as Orion makes its way to the moon.

An artist’s impression of the Orion capsule on its way to the moon.

NASA/Liam Yanulis

What’s Next?

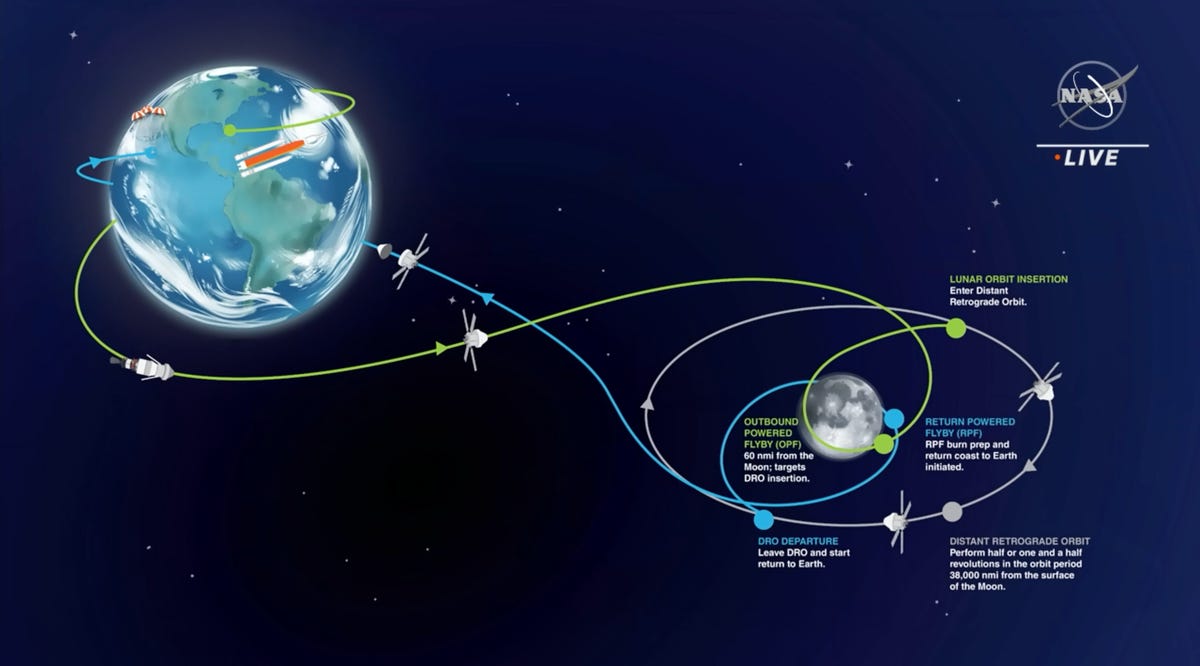

The Artemis team’s extraordinary mission was designed to last up to 42 days — but in the short term, Orion’s major goal is simply to get to the moon.

If all goes as planned, the pointy craft is expected to enter the gravitational field of the moon by about Nov. 21, and shortly after, it will make a close pass of the moon, orbiting just 60 miles from the surface. That should make for some spectacular footage — maybe a re-creation of Apollo 8’s Earthrise?

Cool pics in hand, by Nov. 28, Orion will have eased into a vital orbit around the cosmic body, one that’ll set it up to exceed the distance from Earth that Apollo 13’s crew managed to traverse — the farthest distance humans have ever traveled from our home planet.

Of course, with only dummies on board Orion, Apollo 13’s record won’t exactly be broken, but the capsule is still expected to reach a jaw-dropping maximum distance of around 280,000 miles from Earth. And along the way, it will have dropped small satellites — CubeSats — from universities, manufacturers and other space agencies across the world.

Some of these will image the moon or search for water. Others will test space radiation on yeast, measure particles and magnetic fields or test propulsion systems. There’s also the NEA Scout, which will travel by solar sail to take pictures of near-Earth asteroid 2020 GE, though that target is still subject to change.

Orion’s trajectory around the moon and back is outlined here. Along the way, 10 CubeSats will be deployed.

Screenshot by Monisha Ravisetti/NASA

There are also a trio of mannequins kitted out with a suite of sensors designed to help predict some of the stresses an astronaut could experience on their way off Earth, paving the way for humanity to tackle deep (deep) space adventures one day. “Commander Moonikin Campos” will sit in the would-be commander’s seat during take off and record acceleration and vibration. Helga and Zohar are just torsos with radiation sensors, prepared to assess how space might bombard bodies.

There’s also a modified version of Amazon’s Alexa on board, aimed at decoding how this kind of commercial technology could assist astronauts in space. Yes, you’re right to think of HAL 9000, but we all know Alexa ain’t got nothing on that fictitious, malicious AI (yet).

Though, arguably, the most important test is the Orion capsule’s return to Earth.

Human crew will be enclosed within Orion on Artemis II and a heat shield, also present on Artemis I’s Orion, is critical to protecting them as they crash through the atmosphere at around a whopping 25,000 miles per hour. This shield will basically need to withstand temperatures reaching levels as high as 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit. It was last tested during the 2014 flight test, and a second test, in 2019, tested the flight abort system as well.

But with Artemis I and a working Orion craft, we’ll get to see it all go down in action. Currently, the capsule is expected to make splashdown on Dec. 11.

Crucially, NASA will be testing a “skip entry” technique, where the spacecraft uses the atmosphere to slow down and more accurately pinpoint a landing in the Pacific Ocean.

Artemis II

It’s been more than 53 years since NASA’s Saturn V rocket launched from 39B carrying humans on a journey toward the moon. That mission, Apollo 10, led the way for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to plant their feet into lunar dirt just a few months later (with Michael Collins patiently waiting in orbit from the Command Module) in July 1969.

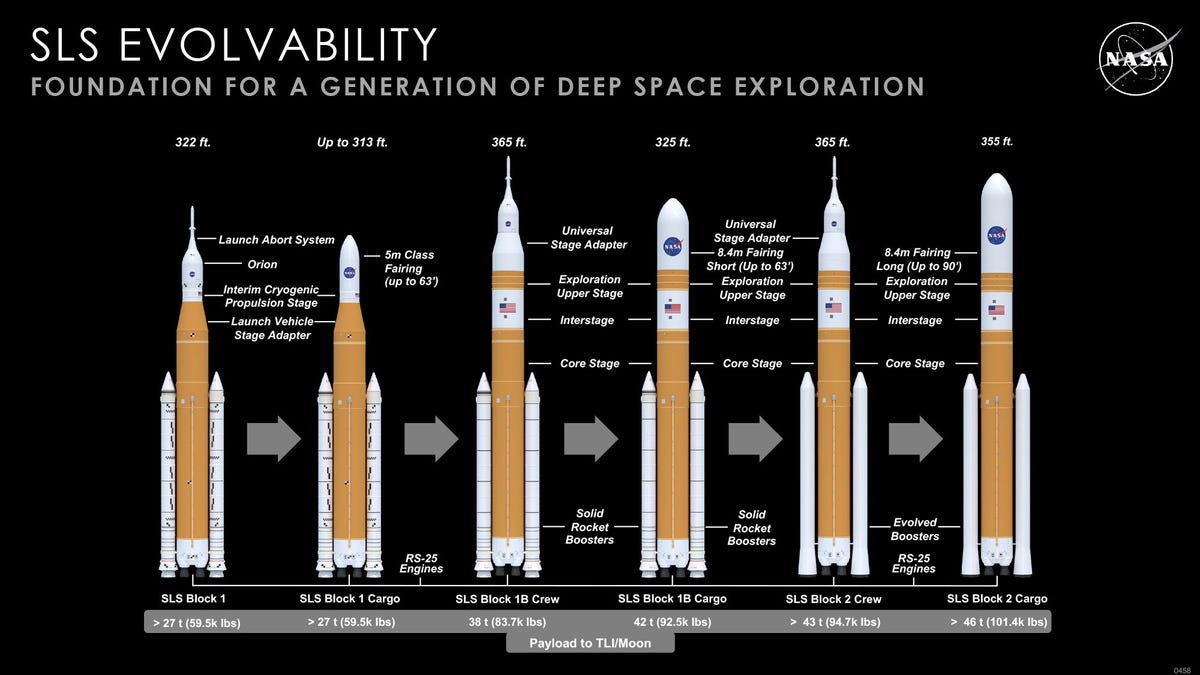

Artemis I plays a similar role: It’s the precursor to Artemis II, a crewed mission around the moon, and then Artemis III, the first to return humans to the surface. Artemis I is designed to be the only uncrewed test flight of the SLS, which places a lot of pressure on it to deliver big on NASA’s desire to return to the moon.

The follow-up mission, Artemis II, will feature three NASA astronauts and one astronaut from the Canadian Space Agency. The fate of that mission rests on the coming weeks for Artemis I. At present, it’s scheduled to launch sometime in May 2024.

An artist rendering of different SLS and Orion configurations.

NASA/MSFC

That will be followed by Artemis III, which is the “Apollo 11” of the Artemis program. Artemis III endeavors to land humans on the moon for the first time in more than 50 years, sometime in 2025. It will feature the first female astronaut to leave a bootprint in lunar soil.