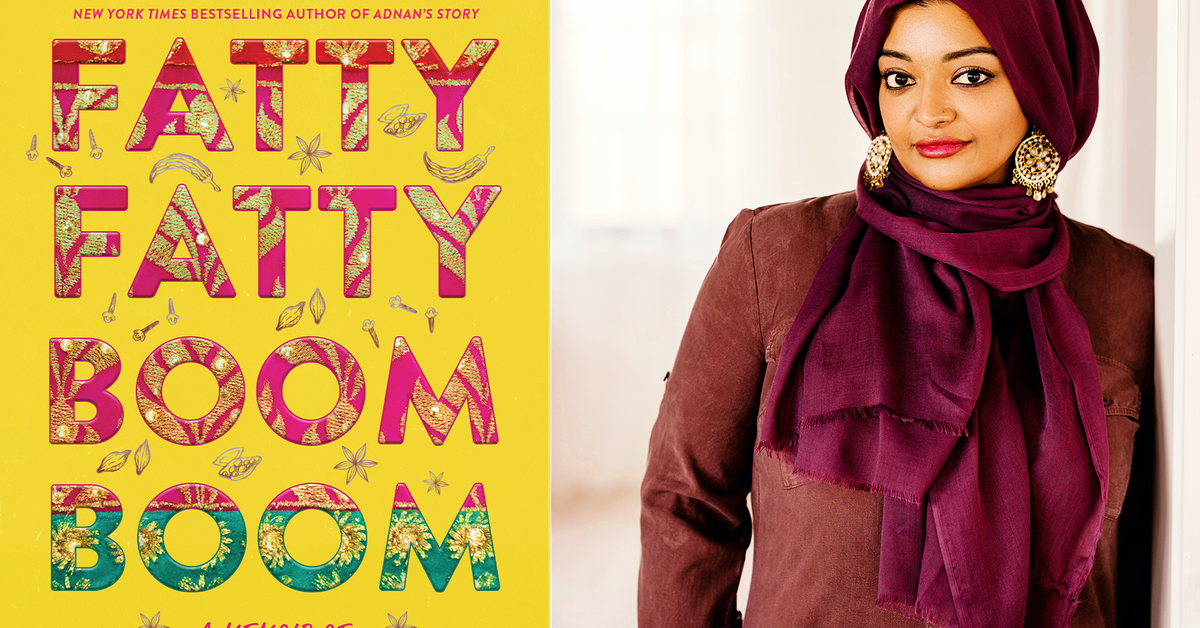

There is plenty of joy to be found in food throughout Fatty Fatty Boom Boom: A Memoir of Food, Fat, and Family, the newest release from author Rabia Chaudry. In a vibrant recounting of her life as a Pakistani American immigrant, Chaudry (also a lawyer, advocate, and producer known for her work with Adnan Syed) writes with fondness of the glistening ghee that completes a bowl of dal; of the sizzling tadka, or spices in hot oil, that constituted “the best sound in the world” to her growing up; of the over-salted omelet she once made for her grandfather as a child, which he lovingly finished anyway. As a baby, she gained relief from teething by eating so many sticks of frozen butter that, she writes, she can still taste it in her mouth today.

But Chaudry — for whom food is fraught, as the book’s title might suggest — doesn’t just leave the reader with pleasant missives about her life of eating well. Underscoring her passion for food are moments that show the deep pain intertwined with eating, like a gym teacher calling out her weight (the highest of her peers) in front of her whole class, and reflections on the world’s mixed messages around food. Recalling a family visit to Pakistan, Chaudry writes: “The abundance of America strained at our skin and clothing, and our relatives were torn between embarrassment for us returning like sheep fattened for slaughter, and mild jealousy at how good the living must be in the States.” Later in life, Chaudry comes to the realization that, for her, food is linked to control, or a lack thereof.

In response to the rampant diet culture of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, we, particularly as progressively minded food-media professionals, have changed how we talk about food. We, increasingly, avoid the language of healthy versus unhealthy, choosing not to stigmatize any one food or behavioral choice. We write about diets and “wellness” with skepticism and derision. In order to avoid the suggestion that any one way of eating is inherently bad, we herald the creations of corporate chains and feel compelled to “redefine” junk food. All of this is warranted, of course, given the myriad ways our culture has shaped fear around food and eating.

Given this context, it is jarring to hear Chaudry say in an interview: “There are foods that are harmful for us — it is as simple as that.” That applies to both villainized foods like chicken nuggets but also highly processed “diet foods,” she notes. Ultimately, Chaudry’s writing is less centered around critique of any particular food, but how an unbalanced relationship to food can indeed cause harm. In recent years, after undergoing gastric sleeve surgery and incorporating circuit training into her life, as discussed in the book, Chaudry has found peace: “80 percent healthy, but give yourself 20 percent,” she says. And in her memoir, she doesn’t seek to wipe the words “healthy” or “unhealthy” from the vernacular, but pushes us to question where our behaviors and relationships to food fall on that spectrum. “I deserve the joy of food,” Chaudry writes. But she adds: “I also deserve not to harm myself with it.” Eater sat down with Chaudry to talk about food, body image, and why the book had to tackle both.

Eater: A lot of people know you for your legal work. How did the decision to do a food-centric memoir come about?

Rabia Chaudry: I have spent over two decades as an advocate and activist on lots of different issues; I felt like I had talked about these issues and that part of my life a lot. I wanted to talk about something that would resonate with a lot of people, something that’s a constant part of my private life that I’ve never shared.

I also wanted to tell a story that people are not used to hearing from American Muslims, from women in hijab, because most of the time when we’re in the media, it’s to talk about terrorism, or it’s to talk about what’s happening in Iran. It’s to talk about very, very niche things and we get pigeonholed. We have the same kind of struggles as everybody else, so I wanted to share that part of my life.

What did you look to for inspiration while writing this book?

I read a few books: food memoirs, and also weight memoirs. It’s not so much that I got inspiration from them in terms of my writing style, but what I realized was that everybody has their own voice, and so I should absolutely not try to mimic anybody. I long ago learned, even as an attorney, to write as much in my tone, as conversationally as possible. It helps humanize your clients; it helps make connections between whoever’s reading it.

It’s interesting that you classify them as food memoirs, and as weight memoirs. I feel like a lot of food books see food as entirely pleasurable but don’t necessarily acknowledge how that can also be harmful. How did you approach bridging that gap?

My two best friends are my fat and my food; my whole life, I couldn’t divorce these issues. People who have had any kind of weight issues or body image issues, it’s directly tied to what they eat, how people tell them to eat, how they deprive themselves, how they eat. At the same time, I really feel like everybody is entitled to abundance and to enjoy their food; we shouldn’t feel punished through it and shamed through it. There’s no way to write about one without the other for me — that’s how my life is, and I think that’s how most people’s lives are.

You write about negative reactions to your weight loss on social media. Given that so much of the book focuses on your love of food, can you tell me more about your decision to discuss gastric sleeve surgery in the book, and how those conversations online influenced how you wrote or thought about it?

I had to think a lot about it, because it’s not something I’ve shared ever publicly; even my own kids don’t know I had it done. When I told my husband or my close friends who did know I had it done that I was writing this book, they were immediately like, “Wait, you’re not gonna include that part, are you?”

We spent a couple of months casually discussing it, but in my mind, I couldn’t write this book without that part. I would feel really inauthentic, like I’m lying to my reader. I’ve been that reader who picks up a book hoping I’m going to discover the secret to getting fit and being well, and I would feel so cheated if somebody gave me that book but actually withheld something so vital. It affects me every single day, for better or worse.

Whether I’m feeling good about myself or bad about myself, that is a relationship between me and my body, and nobody gets to debate how I feel about myself. Society needs a reason to criticize women: You want to get fit, that’s problematic. You’re out of shape, that’s problematic. All that in a basket aside, I was like, I refuse to be shamed on one hand for being overweight, and on the other hand for circuit training for four months and getting in incredible shape.

A smaller part of the book takes place after the surgery. How has that changed your relationship to food?

The first six months to a year were really tough. I had to really prioritize what I wanted to put in my body and I wasn’t prioritizing good things. Over time, your body — the stomach, the sleeve — expands. I love to chug ice water and I couldn’t do that early on, but I can do that now. I can eat anything now, whereas I couldn’t do that in the first year.

The biggest difference is that I now know what it feels like to feel full. I know that sounds crazy to a lot of people; I honestly didn’t know what it felt like to feel full before. If there was food in front of me, I would eat until it was gone versus until I was full. I don’t know if that was some kind of emotional thing. I was like, I just have this limitless space inside me. The feeling of fullness is actually something that I really treasure now.

Now that you have that feeling of fullness and now that it’s easier to approach it physically, how does that change your ability to feel emotional satisfaction through food?

The first year, I just felt starved, even when I wasn’t. It was the emotional hunger of feeling deprived, because there’s just no space. I don’t feel like that anymore, because no matter what I want, I can eat at least a few bites of it. There’s enough space in my sleeve and also I can digest a lot of things I couldn’t early on, so I don’t have that deprivation. If I really want a cheeseburger and I get a cheeseburger, I’ll eat half, but I can eat the other half a few hours later.

You mention that your kids, for example, didn’t know about the surgery. Are these conversations you’ve found space to have in your private life, or does it still feel very private as the book comes closer to fruition?

The themes in this book are conversations I have always had with the people closest to me. My husband and I bonded over this issue — that’s how we got close. It doesn’t matter what my friends look like: From size 4 to size 24, I’ve been surprised over the years that people of every shape and size are still concerned about [body image]. I have a slight anxiety about what it’s going to be like when thousands of people have the book in their hands, but that anxiety is countered with knowing that every time in my life I have revealed something that’s been hard and painful, it’s done a lot of good.

When I started talking about my divorce publicly, so many people came forward and said thank you for talking about this; especially in our community, if you’re divorced, there’s a big stigma. Each of these issues, it took me years to get to the point where I could write about it. Because I felt like I couldn’t solve the mystery [but then] I finally figured it out, is why I could finally write about this publicly.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.