[ad_1]

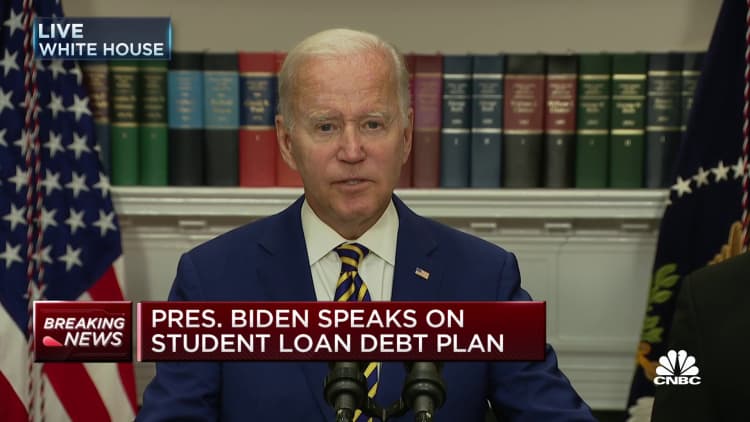

Chip Somodevilla | Getty Images News | Getty Images

The U.S. Department of Education announced on Monday sweeping new changes to the federal student loan system, including additional consumer protections for borrowers and limits on the amount of interest that can accrue on the debt.

“Today is a monumental step forward in the Biden-Harris team’s efforts to fix a broken student loan system and build one that’s simpler, fairer, and more accountable to borrowers,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona, in a statement.

The new regulations should make it easier for students who’ve been defrauded by their schools to get their student loans canceled by the government through the borrower defense process, and allows for the Education Department to come to a determination about these requests for relief as a group, instead of requiring each borrower to individually prove that they were sufficiently harmed or misled by their school.

More from Personal Finance:

How Fed’s interest rate hikes made borrowing costlier

Tips to help stretch your paycheck amid high inflation

‘Ugly times’ are pushing record annuity sales

Under the rules, higher education institutions that accept federal student aid will be banned from requiring borrowers to sign mandatory pre-dispute arbitration agreements or to waive their ability to participate in a class-action lawsuit over their borrower defense claim.

The Biden administration will also curb the practice of interest capitalization — in which unpaid interest is added to the borrower’s principal.

The public service loan forgiveness program, which allows public servants and those who work for certain nonprofits to get their debt canceled after a decade, will also get an overhaul. Months that previously didn’t qualify toward a borrowers’ debt relief, including those when they were in a economic hardship deferment, will be counted. Previously ineligible late payments will also now qualify.

These changes will go into effect on July 1, 2023.

Biden administration officials described these improvements as necessary and urgent to fix a system plagued by problems.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, when the U.S. economy was enjoying one of its healthiest periods in history, only about half of borrowers were in repayment. A quarter — or more than 10 million people — were in delinquency or default, and the rest had applied for temporary relief for struggling borrowers, including deferments or forbearances. These grim figures led to comparisons to the 2008 mortgage crisis.

[ad_2]