Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

Hong Kong

CNN

—

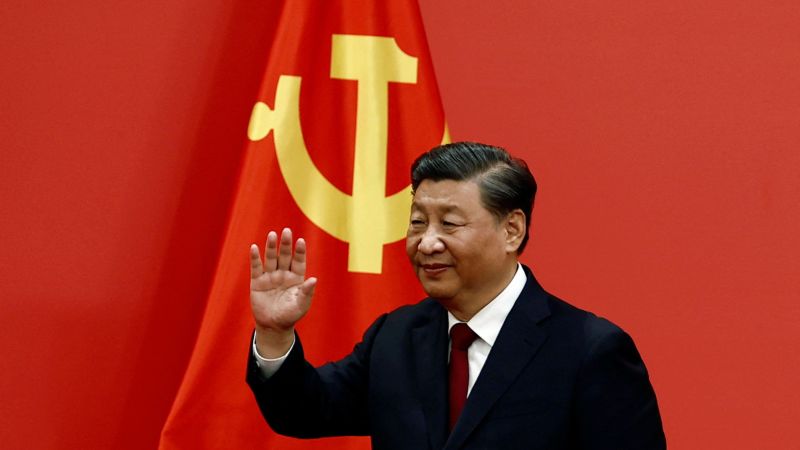

It was a crowning moment for Xi Jinping when he stepped onto a red-carpet stage on Sunday to begin his norm-shattering third term as China’s supreme leader.

Xi, 69, has emerged from the ruling Communist Party’s five-yearly congress with more power than ever, stacking his party’s top tiers with longtime proteges and staunch allies.

That loyal inner circle has not only strengthened Xi’s hold on power – but also tightened his grip over China’s future. To an extent unseen in decades, the country’s trajectory is shaped by the vision and ambition of one man, with minimal room for discord or recalibration at the party’s apex of power.

In the eyes of Xi, China is closer than ever to achieving its dream of “national rejuvenation” and reclaiming its rightful place in the world. But the path ahead is also beset with “high winds, choppy waters, or even dangerous storms” – a dark warning Xi made at both the start and the end of the week-long congress.

The growing challenges have stemmed from “a grim and complex international situation,” with “external attempts to suppress and contain China” threatening to “escalate at any time,” according to Xi’s work report to the congress.

Observers say Xi’s answer to that darkening outlook is to intensify the fierce defense of China’s national interests and security against all perceived threats.

“Xi is likely to tightly control and be involved in all major foreign policy decisions. His packing of the top Chinese leadership with loyalists will allow him to better control and exert influence,” said Bonny Lin, director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) China Power Project.

What he decides to do – and how he goes about doing it – will have a profound impact on the world.

Xi steps into his next era in power facing a significantly different landscape to his previous two terms. The relationship between China and the West has changed dramatically with US-China relations cratering over a trade and tech war, frictions over Taiwan, Covid-19, Beijing’s human rights record and its refusal to condemn Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Xi’s work report, a five-yearly action plan delivered during the congress, pointed to “drastic changes” on the international landscape, including “external attempts to blackmail, contain, blockade, and exert maximum pressure” on China – terms often used by Chinese diplomats to decry US actions.

“It is clear that Xi sees China having entered a period primarily of struggle in the international arena rather than a period of opportunity,” said Andrew Small, author of “No Limits: The Inside Story of China’s War with the West.”

An expectation that ties will deteriorate further “is resulting in a China that is far more openly engaged in systemic rivalry with the West – greater assertiveness, more overtly ideologically hostile positions, more efforts to build counter-coalitions of its own, and a bigger push to shore up China’s position in the developing world,” he said.

These pressures are also likely to impact Beijing’s close relationship with Moscow. While China has sought to appear as a neutral actor in the war in Ukraine, it has refused to condemn Russia’s invasion and instead blamed the West for the conflict – a dynamic that also may be unlikely to change.

“(Xi) already seems to have written off many of the costs that result from (that relationship) for China’s relations with the West, and Europe in particular,” Small said.

At the opening of the congress on October 16, Xi won the loudest and longest ovation from the nearly 2,300 handpicked delegates inside Beijing’s Great Hall of the People when he vowed to “reunify” the mainland with Taiwan – a self-governing democracy Beijing claims as its own, despite having never controlled it.

China would “strive for peaceful reunification,” Xi said, before giving a grim warning that Beijing would “never promise to renounce the use of force.”

“The wheels of history are rolling on towards China’s reunification and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. Complete reunification of our country must be realized,” Xi told the congress to thundering applause.

Under Xi, Beijing has ramped up military pressure on Taiwan, sending warplanes and conducting military drills near the island. Following China’s tacit support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, concerns have only grown over Beijing’s plans for Taiwan.

Lin at CSIS said Xi’s work report does not reveal any major change in Beijing’s policy toward Taiwan, but the leadership reshuffle in the Chinese military could provide clues about his “desire to make more ‘progress’ on unification with the island.”

He Weidong, former commander of the People’s Liberation Army’s Eastern Theater Command, which oversees the Taiwan Strait, was unexpectedly promoted to vice chairman of the Central Military Commission – despite having never served on the body before.

“This suggests Xi is taking very seriously the possibility of a military crisis or conflict and wants to ensure that the PLA is ready,” Lin said. “I do not believe Xi is set on using significant force against Taiwan, but he is taking steps to prepare to do so.”

Xi’s work report also outlined an ambition for China to become more adept at deploying its military forces on a regular basis, and in diversified ways, to enable it to “win local wars.”

“Xi evidently wants the PLA to be capable of winning a war to seize control of Taiwan if he chooses to do that, whether or not his calculations are that this is actually a risk worth taking. That is always the top priority,” said Small, who is also a senior transatlantic fellow with the German Marshall Fund think tank.

Small pointed to a number of risk junctures for an escalation in the Taiwan Strait in the coming years, including the island’s next presidential election in 2024.

“The fact remains, though, that the PLA has not been seriously battle tested in decades, and one of the issues in the period ahead will be whether they can effectively prepare themselves for this,” he said.

Speaking in a televised address on Sunday after announcing his new leadership team – the party’s Politburo Standing Committee – Xi pledged that China’s door to the world would “only get wider” and the country’s development would itself “create more opportunities for the world.”

“China cannot develop in isolation from the world, and the world also needs China for its development,” he said.

But China today is more physically closed off than it’s been in decades. Xi continues to back a costly zero-Covid policy that keeps borders heavily restricted and regularly sends its cities into lockdown – dragging down China’s economic growth.

Xi’s pledge also seems to have done little to assure investors. On Monday, the Hong Kong stock market — where many of China’s biggest companies are listed — had its worst day since the 2008 global financial crisis. Alibaba and Tencent, China’s two leading tech giants, both plummeted more than 11%, wiping out a combined $54 billion in their market caps.

The stakes are high for how the world’s second-largest economy navigates these challenges, especially at a moment where the risk of global economic recession looms.

Xi’s apparent interest in integrating domestic and international security could “translate to policies like sanctions against foreign companies, (and) more red tape when there is foreign investment in Chinese technology companies,” according to Victor Shih, an expert on elite Chinese politics at the University of California San Diego.

And while Xi has said that furthering China’s “international standing and influence,” including by backing global development, is among his main objectives for the next five years, Beijing may no longer be able to rely on the same level of economic engagement to do so in a more divided world.