This story is part of CNN Business’ Nightcap newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free, here.

New York

CNN Business

—

The Nobel in economics is sort of the step-cousin of the Nobel family.

It came about nearly 70 years after its literature and sciences counterparts, in 1969, and is technically called the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences.” It is awarded by the Swedish central bank, in honor of the namesake renaissance man Alfred Nobel who established the prizes.

Some scholars really dislike the economics prize, including one of Nobel’s own descendants, who dismissed it as a “PR coup by economists.”

But hey, it still comes with a cash prize. And it’s also pretty useful in reminding the world that economics as an academic field is, frankly, a barely understood hodge-podge of studies that is constantly evolving and so variable it’s almost useless outside of academia. (And I mean that with the utmost respect to economists, who, not unlike journalists, knew what they were doing when they chose their life of suffering.)

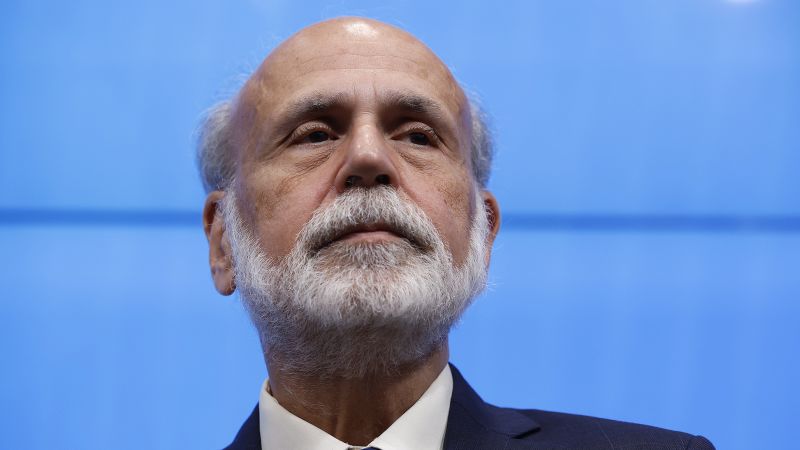

Here’s the thing: Ben Bernanke, the former Federal Reserve chairman who guided the US economy through the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession, was awarded the Nobel in economics along with two other economists, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig. (Congrats to all the winners, with apologies to Doug and Phil, who will forever be referred to in headlines about the Nobel as “and two other economists.”)

Bernanke, who previously taught at Princeton and earned his Ph.D from MIT, received the award for his research on the Great Depression. In short, his work demonstrates that banks’ failures are often a cause, not merely a consequence, of financial crises.

That was groundbreaking when he published it in 1983. Today, it’s conventional wisdom.

WHY IT MATTERS

The timing is everything here. The Nobel committee has been known to play politics (see: that time Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize after being in office for just eight months). And right now, it is using its spotlight to call attention to the high-stakes gamble playing out at central banks around the world, most notably the Fed.

The rapid run-up in interest rates, led by the US central bank, is causing markets around the world to go haywire. And it’s especially bad news for emerging economies.

Monetary tightening — especially when it is aggressive and synchronized across major economies — could inflict worse damage globally than the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic, a United Nations agency warned earlier this month. It called the Fed’s policy “imprudent gamble” with the lives of those less fortunate.

LESSONS FROM HISTORY

On Monday, Diamond, one of the three newly minted Nobel laureates, acknowledged that the rate moves around the world were causing market instability.

But he believes the system is more resilient than it used to be because of hard lessons learned from the 2008 crash, my colleague Julia Horowitz reports.

“Recent memories of that crisis and improvements in regulatory policies around the world have left the system much, much less vulnerable,” Diamond said.

Let’s hope he’s right.

Oh hey, speaking of the Fed inflicting pain: We’re about to see big job losses, according to Bank of America.

Under the rate hikes imposed by Jay Powell & Co, the US economy could see job growth cut in half during the fourth quarter of this year. Early next year, the bank expects to see losses of about 175,000 jobs a month.

The litigation between Elon Musk and Twitter is officially on hold. The two sides now have until October 28 to work out a deal or once again gear up for a courtroom battle.

The big question now is all about the money.

Here’s the deal: Not even the world’s richest person has this kind of cash just lying around. Musk’s wealth is tied up in Tesla stock, which he can’t easily offload for a whole bunch of reasons. He needs to borrow the money, which means he’s got to get banks to pony up.

By most accounts, he’ll be able to make it happen. But the Twitter deal is a harder pitch to make now than it was back in April, when Musk said he’d lined up more than $46 billion in financing, including two debt commitment letters from Morgan Stanley and other unnamed financial institutions, my colleague Clare Duffy writes.

Musk has spent the past several months trashing Twitter as he sought to renege on his offer. Meanwhile, tech stocks have been hammered, ad revenues are declining, and the global economy has inched closer to a recession, sapping investor appetite for risk.

Musk’s legal team said last week the banks that had committed debt financing previously were “working cooperatively to fund the close.”

Twitter is, understandably, skeptical, given the many curve balls Musk has thrown at them since he got involved with the company earlier this year. The company raised concerns last week that a representative for one of the banks testified that Musk had not yet sent a borrowing notice and “has not otherwise communicated to them that he intends to close the transaction, let alone on any particular timeline.”

What’s Musk’s endgame?

No one knows, perhaps least of all Musk. But many legal experts following the case say Musk understood he’d likely lose at trial and then be forced to buy Twitter anyway. He’d rather buy the entire company than be deposed by Twitter’s lawyers and do further damage to Twitter in a trial.

And the banks may not be able to walk away even if they want to.

“The only way they could get out of it is to claim a material adverse effect and that Twitter has changed so much since they agreed to the deal that they no longer want to finance the deal,” said George Geis, professor of strategy at the UCLA Anderson School of Management.

Even if the banks succeeded there, Musk may not be off the hook. The judge in the case could rule that Musk was at fault for the financing falling through — not a far-fetched notion after all the trash-talking — and order him to sue Morgan Stanley to provide the funds or close the deal without it.

Bottom line, it seems like Musk will end up owning Twitter one way or another. And given his only vague musings about what he’d actually do with it, there are a whole host of unknowns lurking in Twitter’s future.

Enjoying Nightcap? Sign up and you’ll get all of this, plus some other funny stuff we liked on the internet, in your inbox every night. (OK, most nights — we believe in a four-day work week around here.)