India has become the go-to destination for many investors — and that’s partly because it’s doing better than many of its peers in a time of economic volatility, economists and analysts say.

But research also shows India has a long way to go toward building infrastructure and enacting reforms that can attract foreign investors, many of whom still find it challenging to do business in the country.

“The Indian economy has held up better than most other economies around the world,” NYU’s Stern School of Business professor of finance Aswath Damodaran told CNBC’s “Street Signs Asia” last week.

“It’s held up in terms of growth, in terms of robustness and it’s also attracting money because where else can the money go, right? I mean, you’ve taken a lot of markets off the table, the money has to go somewhere.”

“The reality is India is benefiting from both having an outlier economy and being a place where capital is going, that too can change over time. But for the moment, I can understand why India is an attractive market for a lot of foreign institutional investors.”

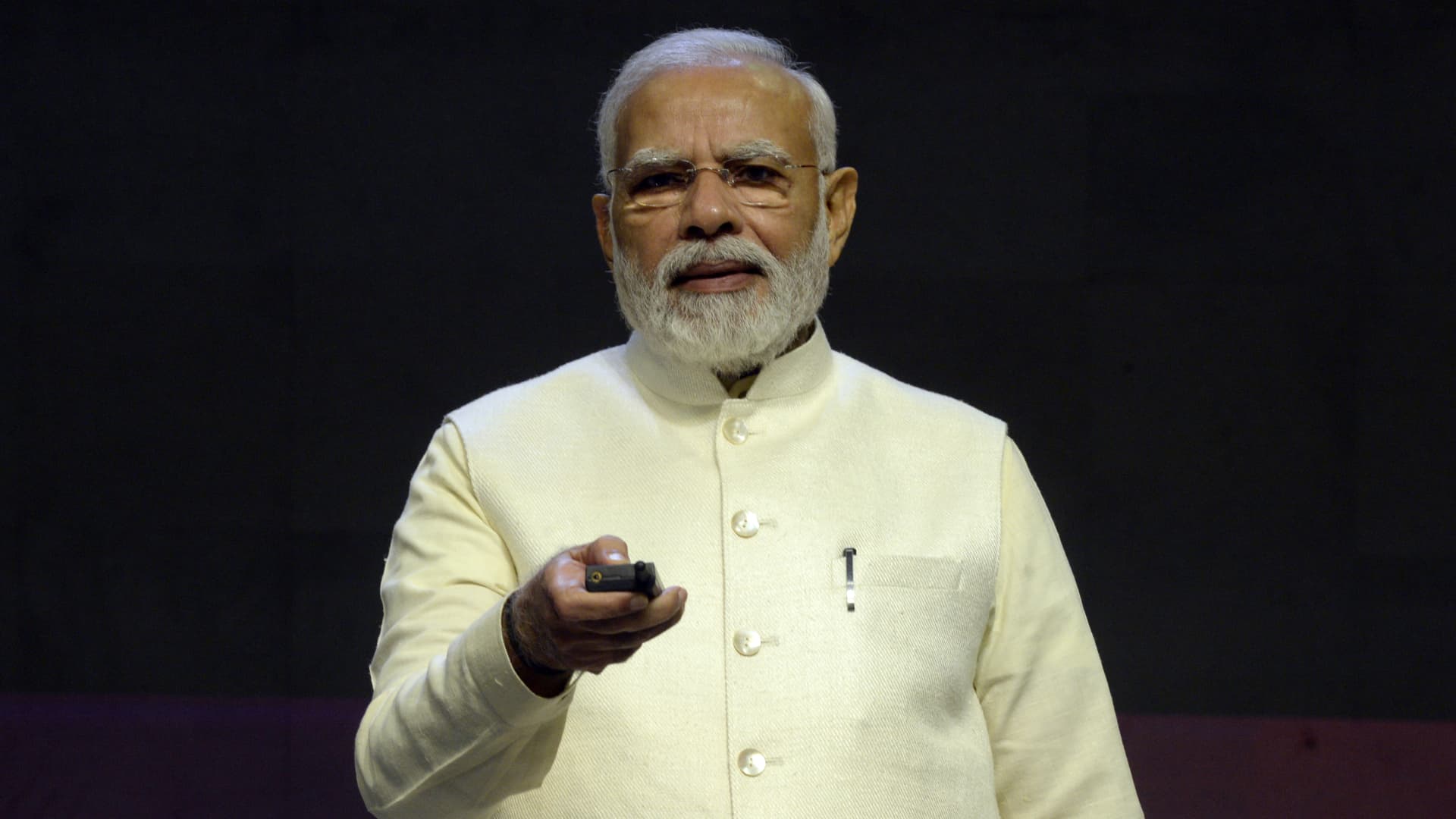

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has plans to make India a $5 trillion economy by 2024-25.

Bloomberg | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Shrinking GDP forecasts

GDP growth forecasts for India for 2022 have continued to decline, whittling down to about 6% in light of global headwinds such as rising interest rates, which raise the prospect of recession.

The U.N. Conference on Trade and Development said India’s GDP growth would slow to 5.7% in 2022, after hitting 8.2% for 2021. For 2023, it is forecasting a lower growth rate of 4.7%. The World Bank also cut its 2022-23 GDP growth forecast for India to 6.5%, from an earlier estimate of 7.5%.

While downgraded, India’s growth forecast still cuts higher than others in the Asia-Pacific. ASEAN+3 (which includes China, Japan and South Korea), for example, is expected to grow at 3.7% this year, the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office reported last week, while economists have pushed down China’s growth forecast to between 2% and 4%.

Inadequate infrastructure

In recent months, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Indian business leaders such as billionaire Gautam Adani have doubled down on marketing India to global investors.

Modi has plans to make India a $5 trillion economy by 2024-25, while Adani said at a recent Forbes conference in Singapore that India will go from a $3 trillion economy to a $30 trillion one in the next 25 years.

But in research conducted to test Modi’s $5 trillion goal last year, Deloitte India said that though the country is a favored destination for foreign direct investments, it has to enact more reforms for that goal to be met.

The report highlighted the need for more FDI in the manufacturing sector, adding that the bulk of investments were driven by the services sector, with manufacturing attracting only about third of the money that goes into services.

A worker preparing vermicelli, which is used in a traditional sweet dish popularly consumed during the holy month of Ramadan at a factory in Allahabad on April 13, 2021.

Sanjay Kanojia | Afp | Getty Images

On top of that, the majority of 1,200 business leaders Deloitte surveyed said India is more challenging to conduct business in compared with countries such as China and Vietnam.

Business leaders in India’s real estate, industrial, and utility sectors find it particularly hard to invest there thanks to low institutional stability and inadequate infrastructure.

“While perceptions of China did take a beating over the past year, the country is still a close competitor to India amongst U.S. investors as a destination for their capital investments,” the report said.

That said, India’s reforms have improved over the years and are moving in the right direction, said Sasidaran Gopalan, assistant professor of economics at the United Arab Emirates University.

Nevertheless, while Gopalan agreed that India “stands out both in its backyard and among other emerging markets” he said it’s not the “only game in town.”

Lee Kuan Yew School of public policy professor in Singapore, Ramkishen Rajan, acknowledged that India’s developing reforms and infrastructure push have caught the eye of investors, but said its trade protectionism continues to be a drawback.

“So India is experiencing a combination of good policy and good luck currently. So overall I understand the bullishness on India, though there is a caveat,” Rajan said.

“While there has been an easing of FDI regulations, India’s reluctance to embrace greater trade liberalization including joining regional trade agreements may hinder the extent to which labor intensive manufacturing will enter the country.”

That would prevent the country from fully using its “demographic dividend,” Rajan said.