[ad_1]

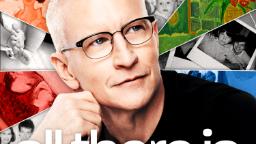

Anderson Cooper, recording

00:00:01

You ready for bed?

Anderson’s son, recording

00:00:03

No

Anderson Cooper, recording

00:00:08

Are you ready for your nap?

Anderson’s son, recording

00:00:08

No.

One of the most unexpected things about having kids is that it’s helped to soothe an ache of loneliness I’ve felt since my dad died when I was ten years old.

Anderson Cooper, recording

00:00:17

Can you count?

Anderson’s son, recording

00:00:21

One, two, three, four. Yay!

Anderson Cooper, recording

00:00:26

Yay!

My son Wyatt is named after my dad, who was 50 when he died while undergoing heart surgery on January 5th, 1978. At some point, my mom had my dad’s things packed up and stored away. She could never bring herself to actually go through them. So now that my mom has died and I’m going through her things, I’m also going through my dad’s. Boxes with some of his clothes, but mostly contact sheets of photographs that he took of my brother and me. Also plays and articles he wrote. In my mom’s apartment, I also found a box of letters that friends of his sent to him in the hospital. Some of them like this one, he never had the chance to open.

Anderson Cooper, recording

00:01:04

“December 29th, 1977. Dear Wyatt, I was so sad when I got your disturbing message that you were in the hospital with a second heart attack. You’re so young. I’m picturing the boys with concerned faces, loving you so and worrying.” He died seven, seven days later.

My dad wrote a book two years before he died called “Families: A Memoir And A Celebration.” In part, he wrote it as a letter to my brother and me because I think he knew he wasn’t going to live to see us become adults. He wanted us to be able to hear his voice in its pages and remember who he was and what his values were. Several years ago, a man named Charles Rua sent me an email with a link to an old radio interview he did with my dad. I was in my office and I clicked on the link and suddenly my dad’s voice filled the room.

Wyatt Cooper, recording

00:01:59

My relationships with my sons is quite extraordinary…

And he was talking about me and my brother.

Wyatt Cooper, recording

00:02:06

…and we understand each other in the most extraordinary kind of way. And I think that that comes because I all my life wanted very much to have children, and quite specifically, I wanted to have sons. So I think they’ve become the recipients of the kind of fathering that I had wanted and had hoped for.

It was the first time I’d heard his voice since I was ten years old.

Wyatt Cooper, recording

00:02:32

My sons are very aware that I have certain expectations of them, and that is that they will behave with honor and with dignity. And we talk a great deal about moral and character values, but also they ask me questions like Anderson, my youngest son, asked, How much does a stuntman make? Because he can’t make up his mind whether he wants to be a stuntman or a policeman. The point is that they know they have choices and that they’re going to be faced with choices.

In this interview, he also read a passage from his book, and it helped me understand something that I hadn’t fully realized, which I want to talk about with my guest, Molly Shannon. Here’s my dad reading from his book, “Families.”

Wyatt Cooper, recording

00:03:12

I see myself and my two sons. In their youth, their promise, their possibilities. My stake in their mortality is invested. I hear those tender and stalwart little men asking the questions I asked, and I watch them wrestling with the answers with which I wrestled and still wrestle. Their rise is my decline. They will be able to jump fences that I will no longer have the will or the call to jump. They will win competitions, perhaps that I never dared to enter. There is rightness in that. There are hope and triumph in it. And it seems good to me. I can help. I can play a part in giving them some of the equipment they will need. Something of courage and understanding. Something of what I have learned. Something of what I am.

And that is what he did. And I’m realizing that for the first time. I may have only had ten years with my father, but it was enough. He did what he hoped to do. He gave me enough of the equipment that I needed. He gave me enough of what he’d learned, of who and what he was. And now it’s my turn to give those things to my sons. Welcome to All There Is with me, Anderson Cooper.

I’m sure you know my guest today, Molly Shannon. She’s a comedian and actor and author. For nine years on Saturday Night Live, she played some of the show’s most memorable characters, some of my favorites, Sally O’Malley, who like to kick and stretch and proclaim. Helen Madden, the licensed joyologist.

I love it, I love it, I love it!

And of course, Mary Catherine Gallagher.

Sometimes when I get nervous, I stick my fingers under my arms and I smell them like that.

That character in particular really stemmed from Molly’s experiences as a child. She was four when her mother, baby sister and cousin died in a car crash. Her father was driving. He’d been drinking and may have fallen asleep. He survived, as did Molly and another sister. She wrote about the tragedy in a book called “Hello, Molly!” and joins me now to talk about how those losses shaped her life.

Hi, Anderson. How are you?

It’s lovely to actually meet you. Yeah, there’s a lot I want to talk to you about, particularly about losing a parent at a young age and how it how it alters one’s future. How much do you remember about your mom?

I just remember little things like that she was folding clothes and I saw a girl outside the window down the street that I wanted to play with. And I was like, How do I…ooh I like that girl and her big tricycle and I want to be friends with her. And my mom was like, you know, you seem like the type that you’re going to have a lot of friends in life. I can tell that you have that kind of personality. So just go up and, you know, introduce yourself and you can say, I’m Molly and, you know, maybe ask her question about her bike. And I remember that she told me that she believed that I would have a lot of friends.

And your mom’s last words were about you and your sisters?

Yeah, about me and my sisters. When she was dying after our accident. This was so strange. My Aunt Bernie’s daughter, my cousin Fran, was in the car, was also killed. She was 25. And it just so happened the night of our accident, my Aunt Bernie’s husband had stopped to help pull people out of the car.

And he spoke to my mother, and he said that her last words were, Where are my girls? Because she was on the ground and she wanted to gather her, her three little girls, and she couldn’t. Her heart must have broken at that moment, you know. And she she she did not make it to the hospital alive. But may God rest her soul.

After the the crash, you were finally told that she was in heaven. How long before you actually understood what that meant?

I think because I was so little, it’s like there’s no way that you could really, like, fully accept that and understand that, you know? So I went into a fantasy waiting for her to come back for a long time. And I thought maybe when we went back to the house that we lived in before the accident, I thought maybe she would be like around the corner. And then I went to grade school, I went to Saint Dominic’s, and I was still like, I think in a fantasy, kind of waiting.

When you were at Saint Dominic’s, just as your mom predicted, you had a lot of friends and you had this sort of play circle where you and another friend were the moms and everybody else were kids.

Yeah, it was like I wanted to reenact, like, a fantasy and be like, a really good mom and the best mom. And it gave me comfort to play that game, family, on the playground every lunch break. But I think my fantasy about waiting for my mom was punctured in fifth grade because this boy, Wally, passed me a note and it was like, Haha, your mom is dead. And I looked at it in class and I just broke down crying and and all these kids, like, huddled around me and they were like, it’s okay, Molly. And I felt so embarrassed. And this one boy, Eric Samus, who ended up going to prison was like, Wally, I’m going to kick your ass how dare you do that to her.

He was like a real bad, bad boy. But he defended me. He protected me. It was like having protection. And I felt very vulnerable and kind of like embarrassed. I felt weak. And I was kind of, I think when you lose a parent, you could either maybe a tough like, I’m fine, or maybe you’re stuck in that place of like, “no fair!” I think it can go one way or the other. And I was more like, tough, like, I don’t need anything. I’m fine. You know.

One of the things you wrote about, which I really related to is, is how no one seemed to understand how deep the ache felt.

And as a kid, I, I so wanted some adult to see the loneliness I felt and sadness I felt. And take me out to a ballgame or just see it. And I was, I was so angry hearing your story that there wasn’t a group of adults who scooped you up and your sister and and did that.

Thanks for saying that, Anderson. I know what you mean. Well, I do talk about that at least Father Murray, right after the accident when we went to church, he was a handsome man with an Irish brogue, a Catholic priest. And he…Nobody wanted to bring up the accident that my mom had died and my baby sister Katie had died. But father Murray kneeled down after mass and held my hands and looked deep in my eyes. And he was like, Molly, I know you lost your mother and you lost your sister. It’s very sad. That’s very hard. And I just…The fact that he did that meant so much to me, just that he could acknowledge the loss, the pain.

My mom used to like this author, Mary Gordon, a lot. And. One of the things Mary Gordon wrote was a fatherless girl thinks all things possible and nothing is safe. And I always think it sort of applies to boys as well. After my dad died, the world seemed a very dangerous place.

But anything was possible. Good things were possible, and terrible things were possible. But nothing ever felt safe again.

I know what you mean. And it’s interesting, you know, you going into war zones and I did crazy physical comedy because I was just like I kind of didn’t care. I mean, of course, I deep down do care, but there was a recklessness in me of like, a wildness.

But your dad embraced that and encouraged that.

He did. He did. He did encourage that. And he…I really like that he was like that. He was like a rule breaker. But then he was a really good father. He would really listen to my stories. And I was very close to him the way you were with your mom. And in many ways I relate to you because a little bit sometimes in those types of situations, you can almost become like the surrogate partner.

It was like my brother, father. You know.

When you were 12, he would give you, like, financial documents to read and go over. I mean, that’s another level. My mom would ask me for advice and I’d be like, Mom, he’s married. He’s not, he’s not going to marry you. Whatever he’s saying, he’s not telling you the truth. I wanted her to give me financial documents because I was like, we’re on a sinking ship and I need to know exactly how much time we have because I got to earn some money.

Oh, that’s so interesting. I’m sure it must have made you so driven because…

Totally, but. But it made you driven, too.

It’s empowering. I mean, some people might say, oh, that’s so inappropriate. They shouldn’t do that to a child. But the good part about it is it makes you feel like a little like king or queen, kind of, like you feel like, well, I’m really capable. And he trusts me with these, like, adult kind of decisions. So there is a boundarylessness to it. But then it was also made me feel great. Somebody once called it empowering abuse.

My mom took my brother and I to Studio 54 twice, once when I was like 11 and once Grace Jones performed. And the other time we actually went with this man, she was dating, Sidney Lumet, this great director, and Michael Jackson. I didn’t know Michael Jackson was, but I remember watching him dance and turning to the person next to me and saying, wow, he’s really good at that. He should pursue it. Because I was very concerned at 11 about how people made a living. So I was like, Oh, he should pursue that. So, but…

So, but your dad, I mean, your dad used to take you and your sister to juvenile detention facilities in order to talk with boys who were there.

Who were in trouble. Yeah, that was really just a Catholic thing. It wasn’t, you know, he felt bad for them and he wanted to help and be a good Catholic.

But like the idea of bringing his daughters there, I don’t know. Some parents might think that’s maybe not a good idea.

Yes, I can understand that. I think for me, because I was going to become a performer, I found it very interesting. It was like a documentary. I was like, huh. But my dad would explain, these boys have no one. They don’t have father figures. They have no one visiting them. So we would stop and buy them potato chips, cigarettes.

Well, I got to say, you also liked bad boys, so I don’t know if it was boring in the juvenile detention facility.

Or if it was just, you know, an added bonus for you.

Yeah, it was an added bonus. I was like, I was curious. I found it really interesting, actually. So I liked that he did stuff like that. It was probably not appropriate, but I found it very interesting.

Can you just tell the story that for him, the greatest prank would be to sneak on a plane and fly somewhere and he dared you to do it.

He said the greatest stunt of all would be to hop on a plane. That would get you on the front page of the paper. So it was his idea and we were like 12 and 13. We took the rapid transit from Shaker Heights to Cleveland Hopkins Airport. We saw two flights, one to San Francisco, one to New York. And I was like, Oh, let’s go to New York. This is 1976, 77. So there were no there’s no security. You can go straight up to the gate. And we just we had our full ballet outfits on and we had our hair pulled back and buns and the pink leotards. And we looked very innocent. But we told the stewardess and we got to the front, we said, Can we just get on the plane and go say goodbye to my sister? And she was like, Go ahead, ladies. And we did. We sprinted to the back of the plane and sat down and hid. And then the plane took off and that was it. And we flew to New York City.

And then the stewardess comes at a certain point.

The same stewardess had given us permission. She was like, was taking drink orders. And she was like, Can I get you ladies something to drink? She looked panicked and we were just like, she realized. She realized these are the girls I let on.

But I love that she made a choice in that moment, do I ring the alarm bells and maybe get fired or just pretend that this isn’t happening?

I mean, yeah, she must have been panicked, like what is going to happen. But she made a decision to not say a word to anyone. And then the plane landed in JFK and we, you know, went up the jetway and we thought we were going to get busted for sure. And she was just like, Bye, ladies, have a nice trip. And that was it. We were in New York City. Isn’t that crazy?

After the break, I’ll talk with Molly about how her childhood experiences became fuel in a way for her creative risk-taking and helped her create characters like Mary Katherine Gallagher.

Oh, my feelings will be best expressed in a monologue from the made-for-TV movie “Long Island Lolita: the Amy Fisher Story.”

We’re back with Molly Shannon. When a parent dies, suddenly, you do find yourself with this other parent who, in my case, I hadn’t known my mom all that well because my dad was such a present parent. My mom was always working and stuff. I suddenly found myself reliant on this person who I needed to then get to know and kind of discover. You wrote, “we were so completely reliant on him,” meaning your dad, “to be taken care of, to be fed, our survival depended on him. So it was terrifying when he would fly into his rages, or even worse, descend into silence, ignoring us.”

Mhmm. Yeah. He would get stressed out because he had to clean the house and make the money. And he was just, you know, a man in the mid-seventies left with two daughters to raise after the car accident. So sometimes when he would get stressed out, he would ignore us. I would have to say, Daddy, are you mad? Are you mad? You know?

But it was very abandoning, very upsetting. I would just have to fix it. But it is definitely a good recipe later for a performer.

You mentioned your dad drank and he would sort of go on benders. He would have parties.

I just want to find the quote that I wrote down. You said, “Oh, God, I hope he’s not smashed. I hope he’s not drunk.” You even talk about kind of the sound of the fork stirring ice in a glass, you would instantly know, and you’d say, Oh, no. It made my heart sink.

I would go check his drink cause he would hide the alcohol sometimes, Did not want me to know. Put a little vodka in the coke. So I would go take a sip to see. I was worried. So that’s why I love coffee, Anderson, because coffee was like whenever there was a party and they put coffee on at the end, I was like, Oh, thank God, the coffee is brewing, you know. Because still I just love the smell of coffee. And yes, so I definitely worried a lot. And his drinking affected me. It bummed me out. And I think you have to be grow up too soon and worry about things you shouldn’t have to worry about.

We were talking about being driven and you said, “I realized I’d been running for years, driven to work so hard on this track, trying to make it, achieve. And when I finally got there,” meaning success from Saturday Night Live, “there was still that ache. But it was a relief to realize fame doesn’t fix anything.” The loss of your mom and your little sister and the experiences with your dad, that was fuel for you, that became fuel to push yourself forward and to succeed, it seems.

Yes, it did. I really was driven to achieve, to make it. I’d been running for a long time. Running, running, running, trying to make it as an actress in L.A. and do shows and audition. And I really wanted to get on television and then I really wanted to be on Saturday Night Live. And then finally I get an audition for SNL, and then finally I get cast and I’m on the show and then I got Mary Katherine Gallagher on and…but I felt really depressed because I was like, oh, I thought that this would fix everything. And I felt like, no, there’s something missing. And it just felt like I really only wanted my mom. I was like, I just wanted her. And I had some thing where I thought maybe if I become famous enough or do backflips or something, then she’ll, like, come back and tell me that she’s so proud of me and she thinks I’m good. And I really cried about my mom for the first time I couldn’t feel it till I was like in my thirties. I just it would have been too much. So I think you just…I was trying to avoid it and then it…you can only run away from that for so long. And the grief about my mom also came up with men, dating men who were unavailable. That pain kind of came up through that. So it was, it was wanting to come out like in my thirties and and I mean, of course it still comes out, of course. But it was it was very freeing, Anderson, because I felt like, I felt like I got to a good place with fame. And I was like, you know what? It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter what level you’re at.

Part of my motivation of throwing myself into work is rage, like the rage of a child who’s lost a parent early on and just angry about that.

But one of the lessons you learned is that you said, “I could get what I want with the break the rules, everything is an adventure, people are mostly good mentality. The world seemed open to me.” And I find it so interesting how different people react to the loss of a parent. Because to me, I became a catastrophist. I was expecting the next terrible thing to happen and I wanted to prepare myself. And I think you have the right mentality. I think that leads to a happier life and a better life than my ridiculous catastrophe thinking.

But you know what, Anderson, I really relate to what you’re saying, because I definitely had all of that. And of course, there’s anger. And what what we’re both talking about is your dad died so young, you were only ten years old. I was four. We had our same sex parent die when we were kids. Their lives were cut short. It’s not fair, you know? So i, like you, also felt like disaster was around the corner and that everything’s going to blow up. So when good things started to happen, like when I got Saturday Night Live, I was like, Oh, no, no, something bad is going to happen. It’s going to blow up. I was very scared. I would not hang anything up on the walls of my office.

That’s me too. I’ve never I…until I moved into this new building here, I never hung up anything in a wall in my office.

So interesting. Yeah. So. Exactly. Because I felt like I was always, like, wanted my stuff like, like just in a bag so I could be ready to move, you know? But I felt like, Oh, I’ve got to work against that. So then I worked really hard in therapy, of course, in my twenties and thirties and was like, I really want to try to just get through this. And now I am the total opposite. I embrace my life, I buy furniture and art, and I’m fully committed to a life on Earth. And I’m like doing it. Of course, parts of that, obviously still the dark parts of ourselves can be doing push-ups in the closet and come out like a beast and surprise you at a moment’s notice. But for the most part, I try to work against it.

You were with your dad at the end of his life?

And I was with my mom. And the final two weeks with my mom were probably the greatest days I ever spent with her. From what I’ve heard of your experience with your dad, at the end, you were in a similar place where there was kind of nothing left unsaid between you.

Exactly. I think I think what it is, too, is when you lose a parent at a young age, it gives you this kind of urgency for life, like this is it. And you don’t take anything for granted, you know? Yeah, so I was so happy that we were able to that I could ask him anything and talk about everything. And right before he died, we went on a trip to Ojai and I asked, Have you ever thought you might be gay? And he was like, Most definitely.

And I love his answer. Most definitely.

He said most definitely. Isn’t that funny? Yeah, he was 72, dying of cancer. And then he told me everything. And I could ask him, like, like your mom, you asking your mom all those questions.

But I do think it’s something that’s so important for people while they have the chance, while their parent or whomever is still alive to have those discussions.

It really is. And so I, like you, was like, oh, this is so profound. I guess because my mom died so suddenly, having that time with my dad when he was dying and in the hospital was so deeply comforting.

How old was your mom when, when she died?

Was reaching 33 and reaching 34 a momentous thing for you in any way, like living past the age that she died at?

That is so interesting. That was around when I was that SNL, probably, or around the time where I got kind of depressed. But I don’t think I thought I was going to die. I was doing dangerous, wild things where I could have broken my neck or really injured myself badly. I was being very reckless with my body, kind of, I don’t care. I don’t need anything. I’m just going to be wild. And it was like punk rock to me. And now I’m the total opposite. I really care. I’m very serious. I would never do anything like that. I’m a mother and so I’ve changed so much. I would never want to put myself in a dangerous situation, you know?

And how, I mean, healing is maybe a cheesy word, but how healing has it been? Your kids are teenagers now, but to be able to be a mom to them like you wanted to have a mom when you were a kid?

Is the greatest. Anderson. It’s just I feel like it’s all I ever wanted to be was a mom and, and now I get to redo what I didn’t have. It is the most cathartic, deep feeling of love and deep, deep healing and so much, I mean, like, it’s, it’s like indescribable joy. How old is Wyatt now?

So he’s two years in like four months and Sebastian is almost six months and they’re so good and like, yeah, this is him.

It’s such a great age. I know, it’s the best thing ever. I’m so besotted with them. Like, I just can’t believe it. And just being with them is so amazing.

I’ve been going through my mom’s stuff and. Is there something you kept of your dad’s or of your mom’s?

Yes. I think what I wanted the most was I loved his little… He,he my dad got sober at Alcoholics Anonymous. He found sobriety through the program. He slipped sometimes, but he really did stick with it, like he was really into it would go to meetings. And so his 12…it’s his little Hazelden 12 Step book…He had little, little like a pep talk that he would do. Like, don’t brag, try to listen to others, you know, the little notes for himself. That ,that means more to me than anything, his little one day at a time prayer book. So I wanted that more than anything. And he wrote a lot about the accident, and I hadn’t read it until just recently. And it was very interesting to read his point of view. You know, how he felt when he heard that they had died. He wrote all about it. He just said, Oh, I sunk into the bed and I said, no, no, no. I didn’t discover all that till recently reading. So my dad wrote a ton. My dad, like your mom was an artist, but your mom really got to live her life as an artist, as an actress, as a designer, as a painter. My dad didn’t have the confidence to go to Cleveland Playhouse to be an actor or a writer, but he did his own writing. And then we did performing in the house, like I call it the Jim Shannon School of Acting, where we would he would direct us in scenes. So he was really a frustrated actor himself, actor, writer.

Somebody who’s listening, who is going through something or still struggling with loss. Do you have advice for somebody?

I liked what you said about, it’s like I don’t want to act like it wasn’t really hard, because you mentioned feeling angry. I felt angry, you know. And I remember performing Mary Catherine Gallagher on stage before I got Saturday Night Live and I was doing like an improvization and my friend John Hoffman said, Oh, you seem angry. And I was like, angry? What? So the anger was coming out in my art, in my comedy, but I didn’t realize it. But I worked really hard in therapy getting over that. It wasn’t like I clicked my fingers. I worked hard in therapy and worked hard on myself to get to a place of peace. And what I want to say, too, is that in Hollywood there can be a feeling of not measuring up. It’s like no matter what you do, it’s like you’re never enough. And I really try to make a conscious effort to be like, You’re enough. Oh, my God, please. Like, I just don’t want to live that way anymore. I’m a mom. I feel like I measure up. I don’t want to live that way in my life on Earth. I try not to buy into that. I feel like you can keep repeating those old patterns of going toward trouble or people who don’t approve or people who don’t really love you or…and I’m just really tired of it. So I try to make a conscious effort to go the other way.

One of the things you said really struck me. You said how you see the loss of your mom now, and you can now look at it and say how lucky you were to have had her for four and a half years. And I, I can look at my dad’s life and say, thank God I had him for ten years because that was, was not what I wanted, but it was enough.

Those ten years have carried me through.

Exactly. And it’s so interesting, Anderson, because you’ll see it like now. It’s interesting being a parent. When I was a mom for four years or my kids were four, I’m like, that was substantial that they got all that. You know, I really see what she gave me for those four years, and I’m sure you’ll see…Ten years is substantial. And your dad, like you said, was probably fighting to stay alive as long as he could for you boys, trying as hard till it was just he couldn’t anymore. And so that is just so deeply meaningful and that you had those ten years and that he left you with this legacy of too, of a book and his values and what he thinks of being a dad and what’s important to him, that he did that for you and for your brother, God rest his soul. It’s just it’s so profound, you know? So we never know how much time on earth we’re going to have with somebody. But I feel grateful. I do feel grateful for the time that I did have, you know.

Well, thank you so much. I mean, I’ve loved you for a long time from afar, and even more so now. And I appreciate your, your honesty and just putting all this out there in the world. We don’t talk about loss and grief enough. And I appreciate you doing that.

Thank you so much. That’s so sweet.

And that’s all there is. Next week, I talk with a filmmaker named Kirsten Johnson, whose mom died of Alzheimer’s in 2007. Now her dad is struggling with dementia.

I didn’t know the term “anticipatory grief” before my mom got Alzheimer’s, but it’s just this crazy feeling of imagining the person dead while they’re in front of you and then all the feelings that that brings. There’s a lot of guilt in it. There’s a lot of just confusion in it because it’s almost sort of unbearable. The fact that they’re not quite themselves already. And then the fact that it’s going to get worse, it’s like you’re standing on quicksand or something.

Kirsten ended up making a funny and really poignant film about her dad’s dementia, and she has some important things to say about how it’s never too late to get to know someone differently and more deeply, even if they’ve already died. I know that may sound like a weird concept, but it’s something to think about. That’s next week. All There Is with Anderson Cooper is a production of CNN Audio. Our producers are Rachel Cohn and Madeleine Thompson. Our associate producers are Audrey Horowitz and Charis Satchell. Felicia Patinkin is the supervising producer and Megan Marcus is executive producer, mixing and sound design by Francisco Monroy. Our technical director is Dan Dzula, artwork designed by Nichole Pesarus and James Andrest. With support from Charlie Moore, Kerry Rubin, Jessica Ciancimino, Chip Grabow, Steve Kiehl, Anissa Gray, Tameeka Ballance-Kolasny, Lindsay Abrams, Alex McCall and Lisa Namerow.

[ad_2]