Fiona was about 1,200 miles southwest of Halifax, Nova Scotia, on Thursday morning, and the area is already bracing for a rare and historic impact.

“Please take it seriously because we are seeing meteorological numbers in our weather maps that are rarely seen here,” said Fogarty.

Lohr, with the emergency management office in Nova Scotia, said the storm has the potential to be “very dangerous” for the province.

“The storm is expected to bring severe and damaging wind gusts, very high waves, and coastal storm surges, intense and dangerous rainfall rates and prolonged power outages,” Lohr said Thursday. “The time to get ready is now before Fiona hits tomorrow evening.”

The lowest pressure ever recorded in Canada was 940 millibars in January 1977 in Newfoundland, said Brian Tang, an atmospheric science professor at the University of Albany. “Current weather forecast models are indicating that Fiona will make landfall in eastern Nova Scotia with a pressure around 925 to 935 millibars, which would easily set a new record,” he said.

A pressure 920 to 944 millibars is typically found in a Category 4 hurricane.

“That storm was much smaller. This one is huge,” said Fogarty.

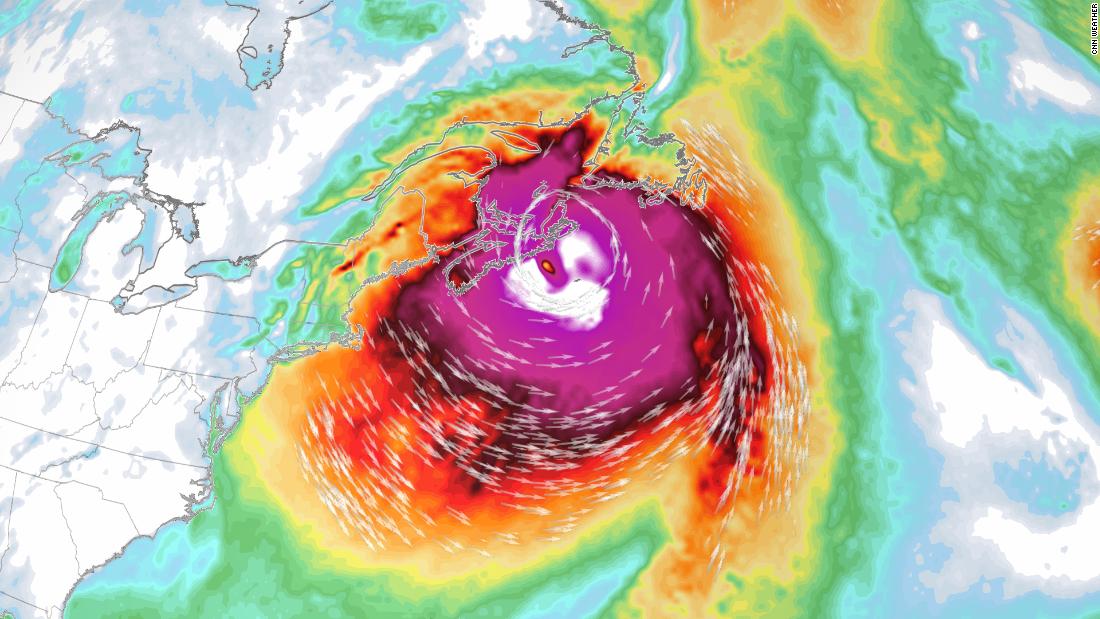

The storm’s hurricane force winds extend 70 miles in either direction from its center — and tropical storm-force winds extend more than 200 miles. A path 140 miles wide could experience hurricane-force winds, and an area more than 400 miles across could experience tropical storm-force winds.

And Fiona could grow even more by the time the storm reaches Canada, according to Tang.

What Fiona could bring

Fiona is expected to reach Atlantic Canada on Friday evening, and the region will begin to experience deteriorating conditions earlier in the day.

“Fiona is purely a hurricane right now. As it begins to interact with a cold weather system and jet stream, it will transition into a superstorm with characteristics of both a strong hurricane and a strong autumn cyclone with hurricane-force winds, very heavy rain, and large storm surge and waves,” explained Tang.

The National Hurricane Center is forecasting the storm “to continue producing hurricane-force winds as it crosses Nova Scotia and moves into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.” In fact, the storm could still carry winds over 100 mph when it slams onshore.

Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and western Newfoundland could receive up to 6 inches of rain, with some areas receiving up to 10 inches. This could result in significant flash flooding.

“We want people to take it very seriously and be prepared for a long period of utility outages and structural damage to buildings,” explained Fogarty.

Life-threatening storm surge and large waves are forecast for the region.

Mike Savage, the mayor of Halifax Regional Municipality, the capital of Nova Scotia, warned wave watchers and surfers to stay away from coastal areas, adding people who live near the coast “must be prepared to move on short notice and pay close attention to possible evacuation orders.”

“Throughout our entire Halifax region you should be prepared for downed trees, extended power outages and local flood conditions,” the mayor added.

Cape Breton Regional Municipality Mayor Amanda McDougall said officials are preparing and working to ensure residents will be safe, as the area is in “the direct impact zone.”

“We need to make sure that there’s going to be a center for people to go to prior to the storm because we know that there are different types of housing that are not going to be able to withstand the winds, the flooding, the way other buildings may,” McDougall said.

Some of the waves over eastern portions of the Gulf of St. Lawrence could be higher than 39 feet, and the western Gulf will see waves from the north up to 26 feet in places, which will probably cause significant erosion on north facing beaches of Prince Edward Island, the Canadian hurricane center said.

The hurricane center also warns of coastal flooding, especially during high tide.

It’s been roughly 50 years since a storm this intense has impacted Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. Both of those were winter storms — in 1974 and 1976, Fogarty said. Many people won’t even remember those two storms, so forecasters are trying to send a clear message for residents to prepare.

CNN meteorologist Judson Jones contributed to this article.