CNN

—

The evening before Michigan’s state primary, Wayne County GOP leaders held a Zoom training session for poll workers and partisan observers – warning them about “bad stuff happening” during the election and encouraging them to ignore local election rules barring cell phones and pens from polling places and vote-counting centers.

“None of the constraints that they’re putting on this are legal,” former state senator Patrick Colbeck told trainees on the August 1 call.

As far as cell phones, “I would say maybe just hide it or something, and maybe hide a small pad and a small pen or something like that because you need to take accurate notes,” Cheryl Costantino, the GOP county chairwoman and host of the call, told participants.

Some participants raised concerns about being tossed out if they broke the rules. “That’s why you got to do it secretly,” Costantino replied.

While volunteer partisan observers have always been trained by political parties and non-profit groups in Michigan, the Wayne County GOP had also invited poll workers – people hired and paid by the local clerk’s office. They are in charge of running the election, and their responsibilities can include checking voter IDs, counting ballots, and even securing voting equipment at the end of the day. Poll workers are required to engage in non-partisan training overseen by the local clerk and are only identified as Republicans for the purposes of making sure there is equal representation of both major parties working the election, according to the Michigan Bureau of Elections.

During the Wayne County training call, obtained by CNN, the presumption that Democrats cheat – thus justifying Republican rule-breaking – permeated the discussion. It offers a snapshot of one of the ways Trump-backing, MAGA-minded conspiracy theorists are intervening in the election process across the country, sometimes encouraging poll workers or volunteer observers to violate election rules in hopes of finding evidence that Democrats might be doing the same.

It’s an approach election experts fear could spur chaos and conflict in November’s mid-term elections and in 2024.

“There is no exception to following the laws; there is no ‘two wrongs make a right,’” said Wendy Weiser, a vice president at The Brennan Center for Justice, which tracks potential insider threats to the election process. Weiser said the center is seeing a spread in efforts by election deniers to infiltrate and manipulate the voting and vote counting process.

“If poll workers are not committed to following the law, to following the directions of election officials, to protecting the integrity of the election process, they can do serious harm,” Weiser said.

Like its counterparts in fellow battleground states Arizona and Pennsylvania, Michigan’s Republican Party has conspiracy believers pushing for influence over the election process at all levels, from candidates for statewide office down to poll workers and observers. As CNN has previously reported, that’s partly due to a strategy by Trump allies of ceaselessly recruiting conspiracy-minded MAGA volunteers for rank-and-file party positions.

Earlier this year, unsuccessful GOP gubernatorial candidate Ryan Kelley called on Michigan poll workers to unplug election equipment “if you see something you don’t like happening.” In June, Kelley was charged with trespassing and other crimes in connection with the January 6, 2021, assault on the Capitol. He has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

The Michigan GOP group Election Integrity Force, which Colbeck helped start, pushes baseless claims about the 2020 election that feed suspicions about the fairness of upcoming elections. In a July session, as first reported by Politico, members of the group coached poll workers and observers to call 911 and bring law enforcement into election-related complaints.

The mounting efforts to influence poll workers have prompted concerns over election disruptions, forcing the state to establish a code of conduct for those individuals, said Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson.

Poll workers who don’t adhere to the rules will be removed “by the local clerk, if they violate the law … or in any way interfere with the administration of fair and secure elections,” Benson told CNN.

The GOP has “made a concerted effort to put election deniers in positions where they can gum up the works, afterward, if they don’t win,” said Jeff Timmer, former executive director of the Michigan Republican Party.

The training sessions are providing a thinly veiled, read-between-the-lines instructions that essentially show “people how to break the law without expressly telling them to break the law, in most cases,” said Timmer, an advisor to the Lincoln Project, a political action committee founded in 2019 by Republicans and former Republicans opposed to Trump.

Both Costantino and Colbeck, the trainers on the Wayne County call, have actively promoted 2020 election conspiracies that amount to make-believe.

In the lead up to the 2020 election, Colbeck posted on Facebook that Democrats were conspiring to commit electoral fraud and “manipulating the vote tallies transmitted from county election boards to the state board of canvassers.”

While serving as a poll challenger at a counting center in Detroit, Colbeck claimed he saw vote-tabulation machines connected to the internet. He submitted an affidavit to that effect for a lawsuit that Costantino filed a week after the election, seeking to stop the results from being certified and requesting an audit.

Costantino’s lawsuit, backed by Trump, drew national attention to her claims of election fraud. But a state circuit court judge dismissed the suit, stating that “no evidence supports Mr. Colbeck’s position.” Noting Colbeck’s Facebook posts, Judge Timothy Kenny said that his “predilection to believe fraud was occurring undermines his credibility as a witness,” before concluding that Costantino’s interpretation of events was “incorrect and not credible.”

Costantino filed an appeal, which was denied.

Colbeck’s continuing claims that machines hooked to the internet flipped votes in 2020 led Dominion Voting systems to demand a retraction from him last year, stating that his claims “are not just false but have been repeatedly debunked by bipartisan election officials, actual election security experts, judges, and numerous Trump administration officials and allies.”

Colbeck also has tried to get copies of election files and Dominion software, zeroing in on Canton Township – a part of his former state Senate district. Canton Township Clerk Mike Siegrist, a Democrat, wrote in an August memo to the town’s board of trustees that his office denied those parts of Colbeck’s public-records requests because releasing the files would “violate our contracts with Dominion and jeopardize future elections.”

Colbeck did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

At the Wayne County election training session last month, Costantino and Colbeck said they were tracking scores of Democrats who Colbeck said “were trying to masquerade as Republicans” while signing up to work elections.

Colbeck told participants, “We’re going to have to keep our heads on a swivel and just start documenting irregularities.”

The two also attacked some election officials by name, including Siegrist, the Canton Township clerk, whom Costantino called “the worst clerk I think I’ve ever dealt with.” She added, “what we have to do is knock him down as soon as possible, before he works his way up in the Democratic Party.”

“He’ll get his due,” said Colbeck, claiming improprieties in how Siegrist handled his records requests.

Colbeck called on the trainees to try to prove his repeatedly debunked theory about vote machines and tabulators being connected to the internet by checking screens whenever possible for connectivity symbols.

Towards the end of the Zoom call, Costantino told the trainees, “So you are all, really, undercover agents. Congratulations. That’s undercover training.”

Approached by CNN at the Michigan Republican state convention, Costantino said comparing the poll workers to spies was just her way of reframing the training session and “make it more fun and interesting” – with Michigan’s open primary serving as a kind of dry run for the election cycle ahead.

“I said just, you know, instead of causing a bunch of scenes and things like that, just write it down,” she said. “Just kind of be like spies and … let me know what’s going on.”

She also said she considered the regulations, outlined in clerk-led trainings that barred cell phones and pens, to be unconstitutional.

“It should not be illegal,” she told CNN, adding, with respect to election fraud claims, “If they’re going to call us out and say, ‘prove it,’ we have to be able to prove it.”

While poll challengers are partisan observers “empowered by a political party to witness the election and to bring up legal concerns in real time as they witness them,” poll workers are supposed to be neutral election officials who assists voters and “make our democracy function,” Siegrist said.

Most of the people who come to his office to apply to be poll workers are suspicious about elections, he said, but being a part of the process helps resolve their concerns. It’s why Siegrist remains optimistic that election workers will do the right thing.

“Those same individuals who come in as almost critics of the process, become the process’s most staunch and ardent supporters,” he said.

The rules about phones and pen and paper aren’t uncommon, said Jennifer Morrell, a co-founder of The Elections Group, a nonprofit led by former elections officials that focuses on protecting the election process.

“Anytime we had anybody working around ballots, we’d ask them not to have a pen, to eliminate any perception that anybody might mark a ballot,” she said.

Trainees on the call, some of whom went on as poll workers in Michigan’s primary, seemed in tune with the premise and advice from Costantino and Colbeck.

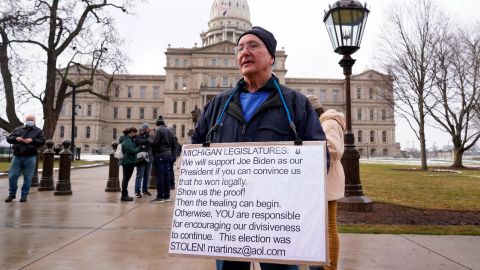

One participant, Martin Szelag, attended a rally last year outside the Michigan Capitol with a sign hanging around his neck that read, in part, that “This election was STOLEN!” and that “we will support Joe Biden as our President if you can convince us he won legally.” Szelag told CNN he worked in the primary feeding ballots into a tabulating machine, and that everything “did happen in an orderly fashion.” Szelag, who said he trusts and admires Colbeck, doesn’t believe Biden was the legitimate winner of the 2020 presidential election.

Larry Ludtke was among the trainees who had concerns about bringing pens and paper on the Zoom call, though he told CNN he didn’t recall bringing that up. He said he wouldn’t say Democrats stole the 2020 election, but that “there is fraud in every election.” Ludtke, who was a poll worker in the Michigan primary, noted that “everything seemed to work out – I got no real complaints.”

Gerry Hermann – a supporter of Colbeck’s unsuccessful 2018 campaign for governor of Michigan – also took part in the session. Hermann serves as the co-chair of the Washtenaw County Republican Party’s Election Integrity Committee, which is responsible for “restoring credibility to Michigan’s badly broken election system.” When contacted by CNN, Hermann declined comment on the training session.

Also on the call was Mark Ashley Price, who told CNN he did not work in the primary because he’s a candidate. Price serves on the board of the Highland Park School District and is the Republican nominee for Wayne County Executive. Earlier this year, in a Facebook post, Price wrote that former president Donald Trump “was robbed of the 2020 election with cheating.” More recently, in a Facebook post, Price wrote he was “happily part of the MAGA movement.” If elected, under county ordinances, Price would have a broad range of powers where he can “supervise, direct, and control functions of all departments of the County except those headed by elected officials.”

Similar election-training efforts predicated on 2020 election conspiracies have been mounted by an array of national and state-level groups with innocuous names such as the Election Integrity Network, True the Vote, Clean Elections USA, and others, along with the Republican National Committee.

True the Vote, which has trained poll observers in various states, was a primary source for the thoroughly debunked film “2000 Mules,” claiming that election fraud cost Trump the 2020 election. Clean Elections USA is organizing a multi-state effort to have observers watch drop-boxes this fall to deter supposed vote fraud.

The Election Integrity Network is a group organized by Cleta Mitchell, an attorney and Trump ally who has been among the most active promoters of election conspiracies. They have conducted events in Michigan and at least seven other states.

“We’ll be able to make sure that there’s another set of eyes going on, watching the ballots, watching the voting, watching the process – knowing what’s going on in the election offices,” Mitchell told CNN.

Morrell, of The Elections Group nonprofit, said her organization sent a contractor to an election training in Pennsylvania led by the Election Integrity Network. The Wayne County training “sounds like the same sort of playbook,” she said.

“We’re dealing with a unique and volatile situation with a group of people operating on their own, outside of the statutory requirements and procedures,” said Morrell. “It creates a recipe for, at best, tense situations, and at worst, escalating to violent confrontation. …They don’t need to see something that’s an actual problem; they could record or take notes of something they don’t think looks right. Whether it is or isn’t may not matter. Just having a loud enough megaphone to say X happened can create distrust.”

And fueling distrust in the election process is the ultimate goal, said Timmer, the former Michigan GOP executive director.

“Their plan is to be a wrench in the gears of democracy,” he said of the Republican-led effort. “That’s their motive. Whatever lipstick or qualifying words they put on this pig, that’s what they intend to do, to cause chaos as the 2022 election unfolds, as a dress rehearsal for the even bigger election in 2024.”