When NASA’s robotic Perseverance rover blasted off to Mars last year, it brought with it a small, golden box called MOXIE, for the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment.

Since then, MOXIE has been making oxygen out of thin Martian air.

And on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, the team behind this contraption confirmed MOXIE has been working so well that its oxygen output is comparable with the rate of a modest Earth tree’s output.

By the end of 2021, extensive data showed that MOXIE successfully reached its oxygen target output of six grams per hour during seven separate experimental runs, as well as in a variety of atmospheric conditions. That includes day and night, different Martian seasons and other such things.

“The only thing we have not demonstrated is running at dawn or dusk, when the temperature is changing substantially,” Michael Hecht, principal investigator of the MOXIE mission at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack Observatory, said in a press release. “We do have an ace up our sleeve that will let us do that, and once we test that in the lab, we can reach that last milestone to show we can really run any time.”

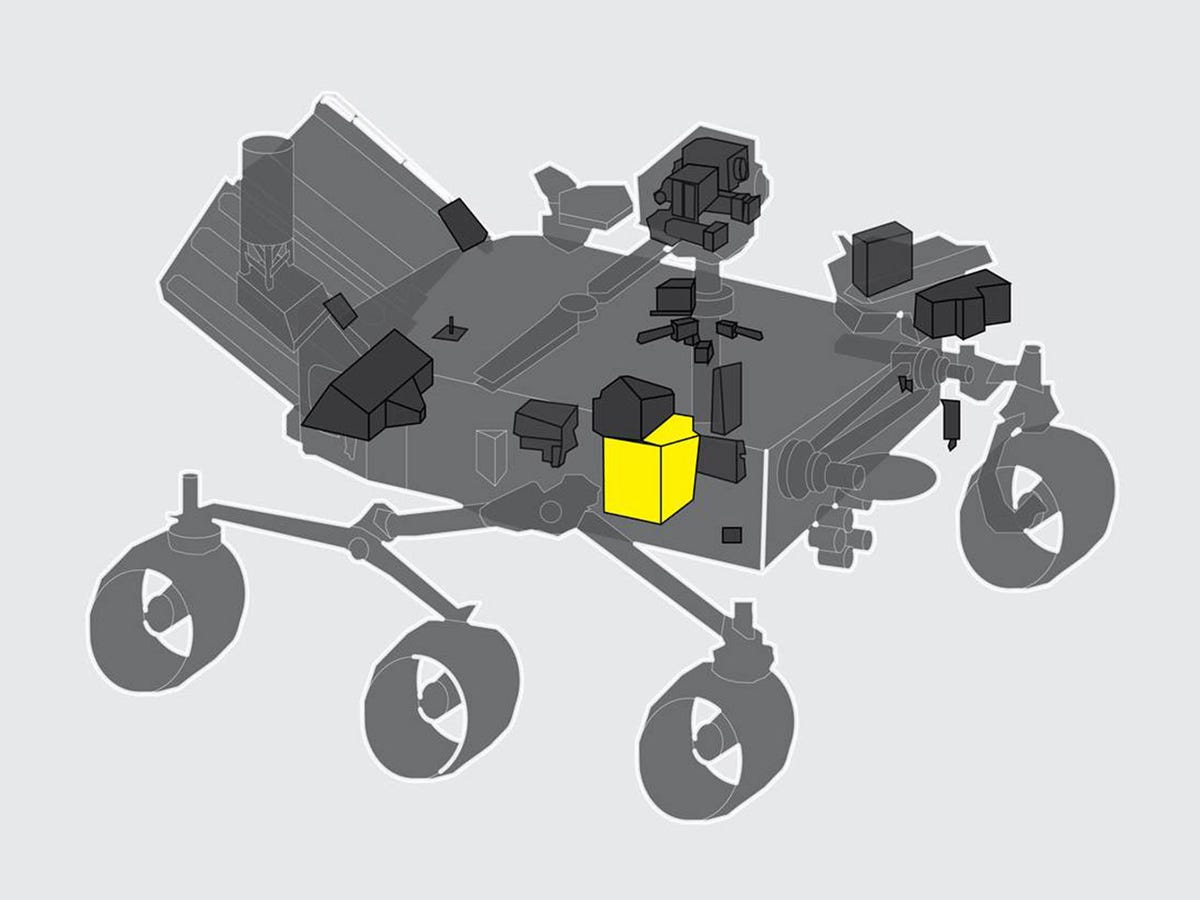

Here’s where MOXIE is located on the Martian rover.

NASA

For scientists and space agencies alike, it’s especially exciting that MOXIE’s promise holds strong, because proposed timelines for astronaut-laden Mars expeditions have looming deadlines for learning how to keep future red planet space explorers safe.

SpaceX CEO Elon Musk’s goal of landing humans on Mars appears to be 2029, for instance, and NASA’s own upcoming Artemis I moon mission is meant to pave the way for Martian excursions planned for the 2030s or 2040s. “To support a human mission to Mars, we have to bring a lot of stuff from Earth, like computers, spacesuits, and habitats,” Jeffrey Hoffman, MOXIE deputy principal investigator and a professor at MIT, said in a press release. “But dumb old oxygen? If you can make it there, go for it — you’re way ahead of the game.”

As it stands, MOXIE is super small (it’s basically the size of a toaster), but this is potentially a good thing. It means that if scientists can somehow scale up the patterned cube’s size, MOXIE could make far more than just six grams of oxygen per hour.

“We have learned a tremendous amount that will inform future systems at a larger scale,” Hecht said.

Maybe one day, the researchers say, it could eventually produce oxygen at the rate of several hundred trees, thus sustaining astronauts once they arrive on Mars and fueling rockets that require the life-giving element to bring crew back to Earth.

“Astronauts who spend a year on the surface will maybe use one metric ton between them,” Hecht said in a NASA press release last year. But, per the space agency, getting four astronauts off the Martian surface on a future mission would require approximately 15,000 pounds (7 metric tons) of rocket fuel and 55,000 pounds (25 metric tons) of oxygen. Bringing all that oxygen from Earth would be supercostly and inefficient.

So, as Hoffman says, why not just make all the oxygen on the arid planet itself?

How does MOXIE work?

On Mars, MOXIE is actively converting carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere — where the element makes up a whopping 96% — into breathable oxygen.

A little chemistry 101 is that carbon dioxide molecules are made up of one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms. Those bits are basically stuck together. But an instrument within MOXIE, called the Solid Oxide Electrolyzer, can sort of harvest the oxygen bits within those CO2 molecules that scientists are interested in. Once complete, all the free-floating oxygen particles are recombined into O2, aka molecules with two oxygen atoms, otherwise known as the kind of oxygen we know and love.

I know it’s different, but I keep thinking about Pixar’s WALL-E doing this. So, as WALL-E would say: Ta-da!

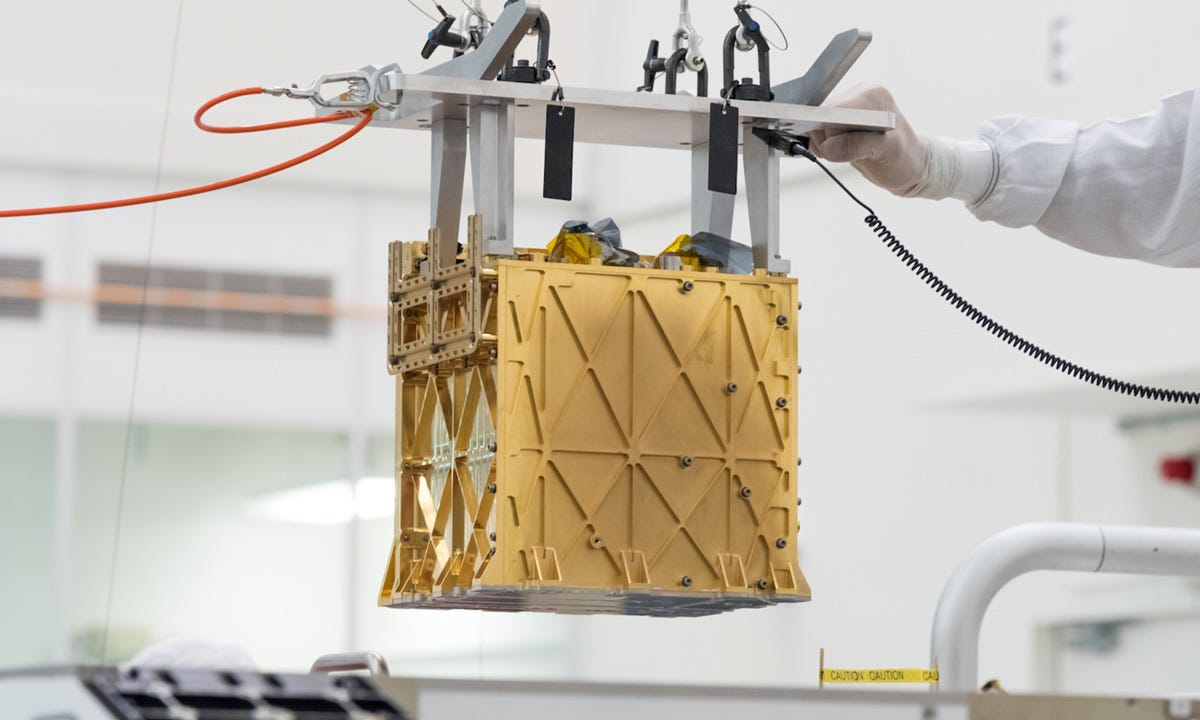

Technicians at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory lower the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) instrument into the belly of the Perseverance rover.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

“This is the first demonstration of actually using resources on the surface of another planetary body, and transforming them chemically into something that would be useful for a human mission,” Hoffman said. “It’s historic in that sense.”

Along the way, this process requires the use of superhigh heat — reaching temperatures of approximately 1,470 degrees Fahrenheit (800 Celsius) — which is fascinatingly what gives MOXIE its characteristic gold coating.

Like with NASA’s trailblazing James Webb Space Telescope, MOXIE has to be shielded from infrared heat because it operates with heat itself. A gold coating does just that, and in fact the JWST’s mirrors are coated with gold for the exact reason, too.

One wing of the James Webb Space Telescope’s main mirror opens into place during a final test of the mirror deployment system in May 2021. Check out that gold-plated beauty.

NASA

Up next, the MOXIE team intends to demonstrate that MOXIE works well under even more intensive conditions, like a next run coming up that’ll occur during the “highest density of the year,” Hecht said. “We’ll set everything as high as we dare, and let it run as long as we can.”