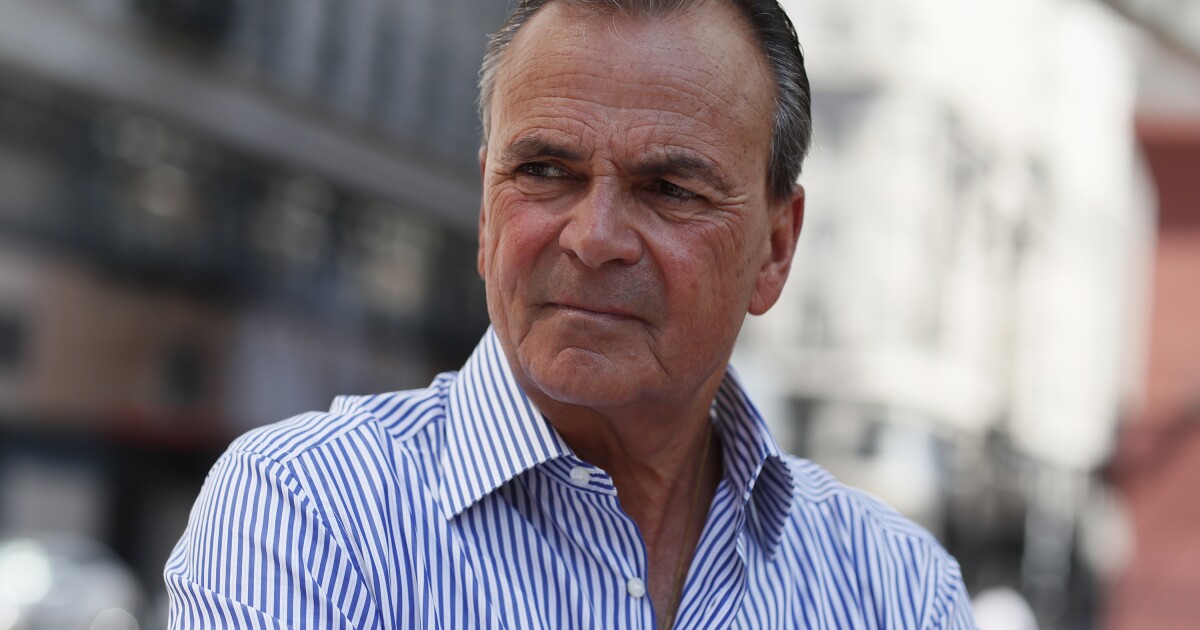

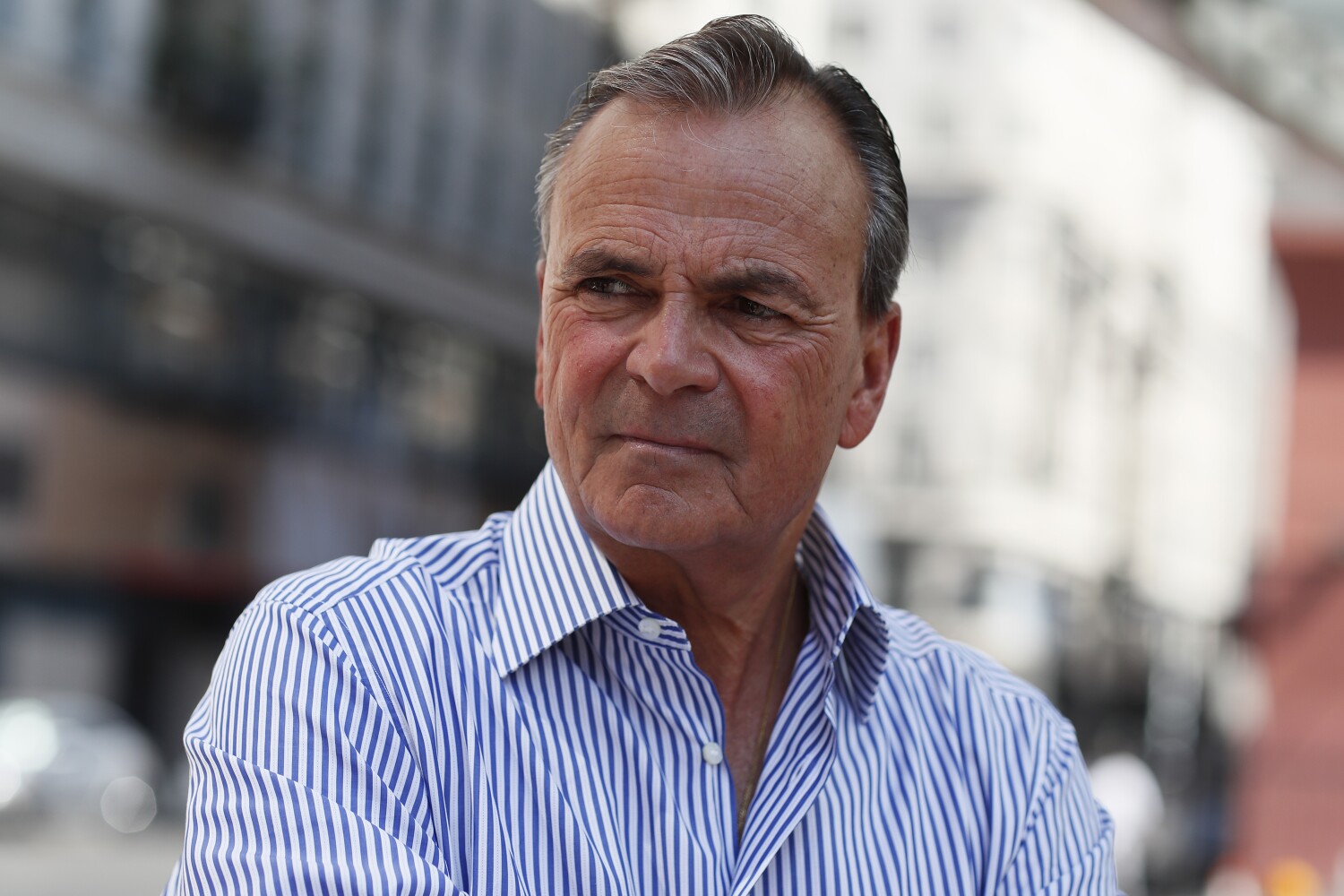

Shortly after Rick Caruso announced his run for mayor in February, he promised to give up day-to-day leadership of his company and put his holdings into a blind trust to head off potential conflicts of interest, if elected.

The mayoral race is still underway, but Caruso moved forward with the first part of that pledge Thursday, stepping aside as chief executive of the real estate development firm known simply as Caruso and elevating company executive Corinne Verdery into the CEO’s role.

But Caruso’s promise to put his holdings, which include the Grove shopping center, into a blind trust, drew fire Thursday from his mayoral rival, Rep. Karen Bass, and two government ethics experts who called it an inadequate step that would invite conflicts of interest.

“Real estate developers have long sought to influence decisions at City Hall. We won’t let that happen in Los Angeles,” Bass said in a Thursday morning tweet.

Caruso campaign spokesperson Peter Ragone countered that Caruso “is the only candidate who has pledged to appoint an ethics czar who will oversee all aspects of his ethics pledges and ensure transparency and sunlight in all his operations as mayor.”

The back and forth over Caruso’s planned blind trust is the latest flareup between two markedly different candidates — one a billionaire developer and the other a career public servant — in the race to lead the nation’s second-largest city.

The Bass campaign held a news conference Thursday morning where Norm Eisen and Richard Painter — who served as the chief ethics lawyers to President Obama and President George W. Bush, respectively — castigated Caruso’s planned course of action. The pair published an op-ed in Slate on Wednesday afternoon, sharply critiquing the conflicts Caruso could face if elected as mayor.

In a city roiled by a series of corruption scandals that have put increased scrutiny on the relationship between developers and L.A. City Hall, Eisen and Painter appear to question whether existing laws and standards go far enough to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Bass, who is on vacation this week, did not attend the Zoom news conference. Her campaign declined to say where she was.

The Caruso campaign said Thursday that if he is elected, a separate trustee would be appointed to oversee that overarching blind trust, which would also include his substantial stock portfolio. Whether the development company retains Caruso’s name if Caruso is elected will be up to Verdery, Ragone said.

Ethics experts have generally said that Caruso’s business holdings do not prevent him from holding office, as long as he properly discloses his financial interests and carefully follows protocol around potential conflicts as they arise.

Eisen and Painter have taken a far more stringent view. They suggest that to truly avoid ethical issues if elected, Caruso should have an independent trustee sell his real estate holdings in and around the city and put the proceeds in something conflict-free, like a diversified mutual fund.

“It is critically important to insist the mayor be free of conflicts of interest and that this real estate empire be sold if Mr. Caruso were to be the next mayor of Los Angeles,” Painter said Thursday.

Bob Stern, co-author of the state’s 1974 Political Reform Act and former general counsel for the California Fair Political Practices Commission, seemed mystified by the suggestion, saying he didn’t know of a law anywhere in the country that would require such a step.

The state’s provisions around blind trusts are clear, Stern said.

Unless an individual gets rid of the assets in the blind trust, they are not considered truly “blind,” and conflict-of-interest rules still apply. But that doesn’t mean an individual has to liquidate their assets to avoid conflicts of interest: He or she would just have to recuse themselves from acting on matters directly affecting their assets, Stern said.

In Caruso’s case, that would likely mean avoiding ordinances or contracts that specifically involve one of his properties.

Broader decisions about development in the city that are not directly related to Caruso’s properties would not be considered a conflict under the law, Stern said.

“In a sense, his biases are there whether he owns the property or not. He’s very business-oriented,” Stern said. That perspective, however, would hardly come as a surprise to Los Angeles voters — Caruso has made his business success a central part of his campaign.

When asked how Caruso would approach hypothetical city decisions that might indirectly benefit him as a developer, Peter Ragone said: “The law allows for many established options for Rick to avoid conflicts of interest, when they truly exist, including recusal.”

Others, like Carmen Balber, executive director of advocacy group Consumer Watchdog, took issue with how Caruso might generally benefit from a pro-development approach in the city.

“He cannot forget that he’s a developer and he does better when rules favorite developers,” Balber said. “No matter how strict the creation of a trust is for Caruso, the details of his actions in office — and whether or not he’s still engaging in decision making that might benefit him personally — will need tough scrutiny.”

L.A.’s mayor has considerable sway over land-use decisions in the city. He or she has the power to hire and fire the top manager at the Department of City Planning. He or she would also have the authority to replace the nine members of the city’s planning commission, a panel of volunteers that vets large-scale development projects.

Caruso’s business has been enmeshed in a fight over plans to modernize and expand L.A.’s storied CBS Television City studios, located across the street from the Grove, raising questions about how he might handle such projects as mayor.

But an elected official with substantial personal wealth — and assets in the region they govern — would hardly be unprecedented in Los Angeles or California.

“Many local officials and statewide officials who have assets will oftentimes create a blind trust,” retired attorney Colleen McAndrews said, noting that the practice became more commonplace after the state’s Political Reform Act was adopted.

McAndrews, a former member of the state Fair Political Practices Commission, advised Arnold Schwarzenegger on setting up a blind trust when he became governor. Gov. Gavin Newsom also put his hospitality business, the PlumpJack Group, into a blind trust when he took office and did not liquidate the individual businesses.

The closest parallel to Caruso’s situation would likely be that of Richard Riordan, an affluent businessman who served as L.A.’s mayor for two terms beginning in 1993.

Riordan paid a $3,000 fine for violating the state’s conflict-of-interest law in 1996 over an issue that his office called an inadvertent mistake, but Stern and others said conflicts were not a major issue during his administration.

McAndrews, who also served as Riordan’s attorney while he was mayor, said she would hold trainings with city staff so they would know what the then-mayor’s assets were and be able to spot potential conflicts as they arose.

But Eisen, the former Obama lawyer who co-authored the Slate op-ed, argued that merely complying with existing conflict-of-interest law wouldn’t go far enough to meet ethical best practices.

Eisen said that he and Painter had offered to provide Bass informal, pro bono guidance on the potential ethical issues in play. When asked why they didn’t similarly approach Caruso before laying out their concerns in a public op-ed, Eisen said he knew Bass from her service in Congress.