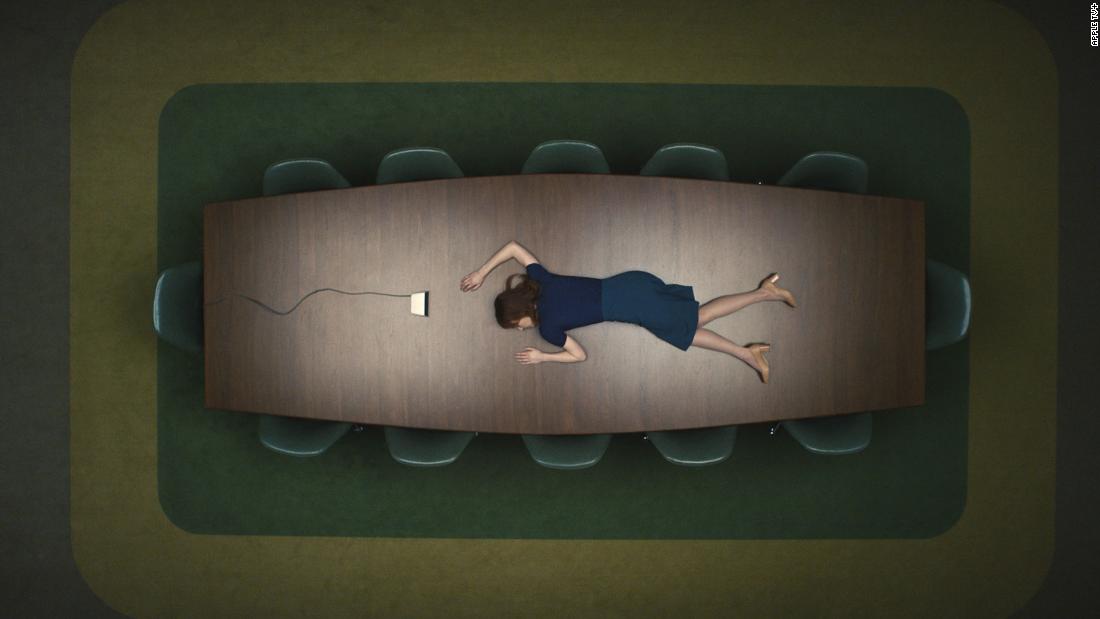

The boardroom where she’s “birthed” into life as an innie at Lumon, the mysterious corporation at the center of “Severance,” is also a womb of sorts. And when she leaves it, she’ll be confined only to the contained, labyrinthine world of the Lumon building, which doubles as a mid-century prison.

Jeremy Hindle, “Severance’s” Emmy-nominated production designer, took the “birthing” metaphor and ran with it, creating a world within a world at Lumon. It’s a spare, meticulously designed environment that, at first blush, is impressive and aesthetically pleasing. But the longer you spend within Lumon, the more menacing it becomes.

“It should be this beautiful environment, but also, they’re experimenting on them underground,” Hindle told CNN.

The details, big and small, that make ‘Severance’

Part of the allure of “Severance” is its inability to be placed in time, an effect that was created with painstaking detail, Baseman and Hindle said. There are clear nods to the mid-century offices of “Mad Men” or “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” structures that are stylish, precise and somehow still practical. (The exterior of the Lumon building was shot at an existing mid-century building, the Bell Labs Holmdel Complex in New Jersey.) But the very concept of “Severance” makes it feel like a futuristic dystopia.

“Part of the mystique of ‘Severance’ is, you’re just not really sure where you are or when you are,” Baseman said. “We just wanted to create a new world we hadn’t seen before.”

To do that, Baseman said, the team behind the series — including executive producer and director Ben Stiller and showrunner Dan Erickson — focused as much on the background minutiae as they did the broader design. There’s not a pen out of place within Lumon — even the fake foods in the office vending machines were selected with a purpose.

The cars its characters drive are slightly outdated station wagons and similar models; the desktop computers the core four innies work at are bulky, rounded and retro. Patricia Arquette’s opaque, eccentric character with a dual life required double the details — at work, where she’s Ms. Cobell, her office is scantly decorated; at home, where she’s Mrs. Selvig, her home is a mess of burnt cookies, framed needlepoints devoted to Lumon’s tenets and that disturbing shrine to a Lumon luminary. Many of those details may never make it into frame, Baseman said, but they contribute to the haunting atmosphere — and provide fun Easter eggs for eager viewers to catch during a rewatch.

The office that feels more like a ‘playground’

The main office set for the “Macrodata Refinement team,” where Helly (Britt Lower), Mark (Adam Scott), Irving (John Turturro) and Dylan (Zach Cherry) spend their entire innie lives, sets the tone of the show, Hindle said. The wide, white-walled room is drenched in fluorescent light, with an island of four connected desks in the center against an astroturf-green carpet.

“It’s the weirdest room ever,” Hindle said, comparing the jungle gym of desks to “an umbilical cord underground.” (Another birthing allegory!)

The ceiling is purposely too low — around 7 feet, 9 inches, Hindle said — to create a feeling of comfort and snugness and, conversely, claustrophobia and menace. And the details within the office — the oddness of the desktop computers, the meticulously neat kitchen and supply closet, the perfectly manicured “lawn” of carpet — are meant to seem more like props on a set than practical components of an office, Hindle said.

“These are children in an office environment,” he said. “The green is like a playground, the desk is a little apparatus you get to play on.”

And if the office reminds viewers a bit of the Discovery One of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” that’s a good thing, Hindle said. The office is downright Kubrickian — beautiful in its spareness and symmetry, but disconcerting in its emptiness. That cognitive dissonance isn’t too far off from what the innies and outies feel once they’re severed.

“I treated it like a spaceship,” he said of the main MDR office set. “The best sci-fi is really claustrophobic, but you really want to be there.”

The hallways from hell are real

Perhaps the creepiest part of the Lumon offices, though, are its seemingly endless, blindingly bright hallways. They become narrower and wider as characters move through them, and that’s not just a trick of the camera, Hindle said: The crew built the labyrinth of hallways on set, so when the actors are zipping through them for what feels like minutes, they’re really doing it. It’s a practical effect that, onscreen, makes audiences feel like they’re marching with the innies — and, on set, made the actors quite uncomfortable, Hindle said.

“We were torturing them in a weird way,” he said slyly.

Lumon green serves a purpose

Though Lumon’s color palette is largely drab grays and stark whites, the monotony is broken up throughout with pops of green. There’s the stark green carpet of the MDR office; the artificial greens of the fake plants that populate the office; green upholstery in the boardroom where Helly is “born” and the seating area near the one, hellishly narrow elevator.

“I see it as off-putting,” Baseman said. “Green is often ‘green with envy,’ illness; it’s also life. It’s a mix of all of that.”

The green of the MDR office carpet resembles a pasture, Baseman said, on which the innies are meant to “play” while the Lumon higher-ups observe them.

Even when Irving and Burt (played by Turturro and Christopher Walken, respectively) share a moment of vulnerability in the supply room, surrounded by lush greenery, those plants are fake, too. They suggest the notion of life — an artificial one, like that of an innie.

The spare innie world vs. the cluttered outie world

The “Severance” crew decided early on that the innie world should look just bizarre enough that, if anyone from the inside made it out, no one would ever believe them about what they saw, Hindle said. But the world of outies has its own unique visual language that often feels bleaker than the Lumon sets do.

When Devon and Ricken, Mark’s sister and brother-in-law, appear onscreen, warm oranges and golds enter the color palette of the series. They’re wholly unconnected to Lumon (as far as viewers know) and share a loving, healthy relationship. But Mark’s outie self is alone in a blue, permanently darkened townhome — Lumon corporate housing — with hardly a personal touch in his place. (There is a lone framed poster for vintage bicycles leaning against a wall, Baseman said, a detail Stiller suggested that teases Mark’s former life.) We know, clearly, from spending time with outie Mark that the process of severance hardly solved his problems.

But Hindle wondered if Lumon got it right: An average desk at an office today is likely adorned with family photos, mementos and other personal flourishes that make one’s workspace feel “homier.” But when work and home life bleed into each other, severance seems more and more appealing.

“They were really pristine, immaculately designed and there was nothing personal at your deks,” Hindle said of the mid-century offices of yore. “People are treated like cattle now. They let you bring your family to work, and that’s why you’re willing to be a slave to this thing. I kind of wonder if severance is better, in a funny way — you go to work, do your work and go home.”