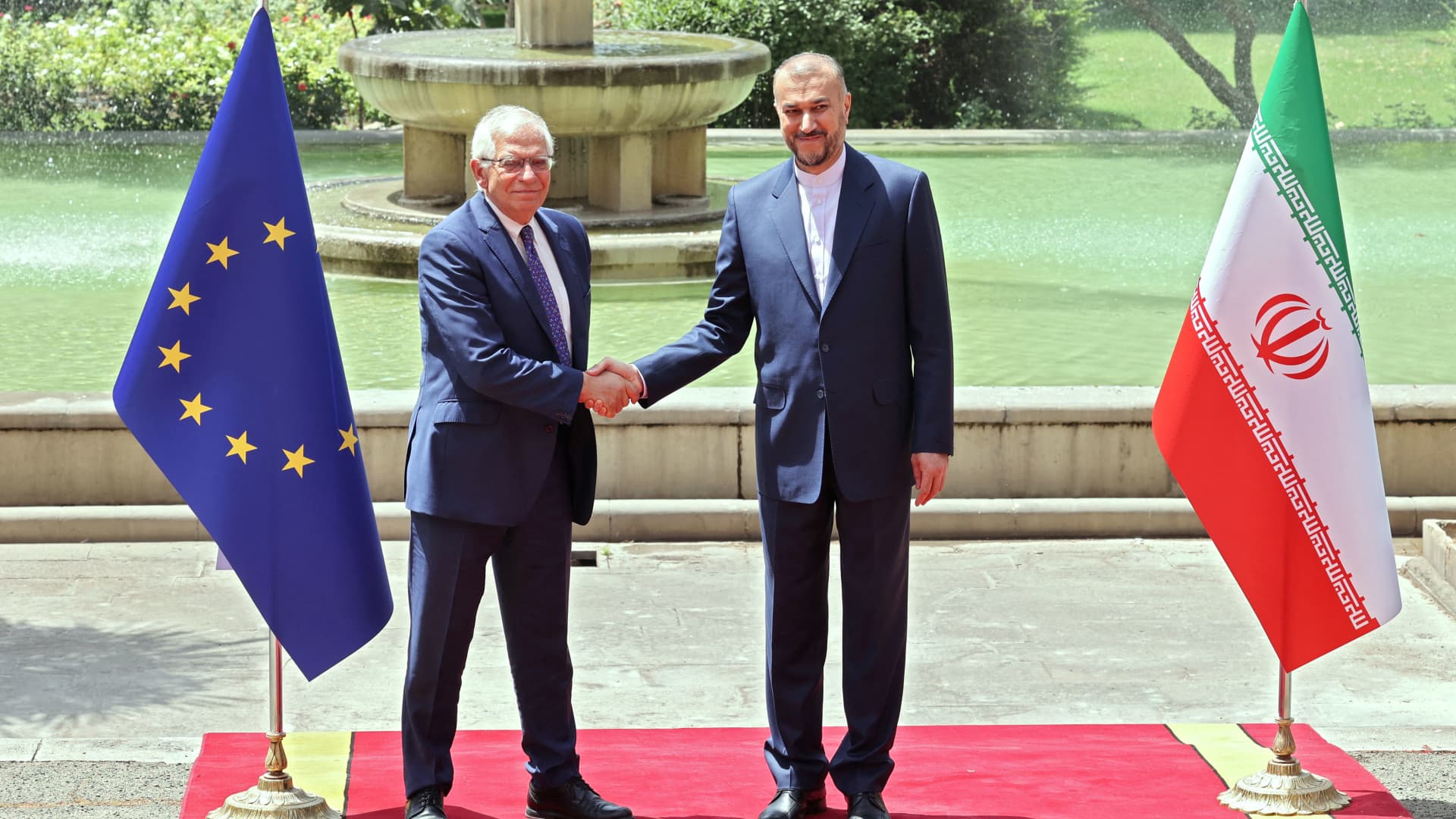

Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian (R) meets with Josep Borell, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (L), at the foreign ministry headquarters in Iran’s capital Tehran on June 25, 2022.

Atta Kenare | AFP | Getty Images

Iran appears the most optimistic it’s been in years about finally clinching an agreement on a renewed version of the 2015 nuclear deal with the U.S. and other foreign powers.

Iranian negotiating team adviser Mohammad Marandi said on Monday that “we’re closer than we’ve been before” to securing a deal and that the “remaining issues are not very difficult to resolve.” And the European Union’s “final text” proposal for the deal, submitted last week, has been approved by the U.S., which says it’s ready to quickly seal the agreement if Iran accepts it.

Still, there are obstacles to rescuing the Obama-era pact, which lifted sanctions on Iran in exchange for a range of limits on its nuclear program. Iranian negotiators responded to the EU’s proposal, pointing out the remaining issues that may yet prove impossible to reconcile.

And the stakes are high: the more time goes by, the more Iran progresses in the advancement of its nuclear technology — far beyond the scope of what the U.N.’s nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and the 2015 deal’s original signatories say is acceptable.

That could risk triggering an all-out war in the Middle East, as Israel has threatened military action against Iran if it develops nuclear weapons capability.

An Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) military personnel stands guard next to two Iranian Kheibar Shekan Ballistic missiles in downtown Tehran as demonstrators wave Irans and Syrian flags during a rally commemorating the International Quds Day, also known as the Jerusalem day, on April 29, 2022.

Morteza Nikoubazl | Nurphoto | Getty Images

Already in the spring of 2021, IAEA chief Rafael Grossi said of Iran that “only countries making bombs are reaching this level” of nuclear enrichment.

With a revived nuclear deal, the U.S. and the deal’s other signatories — France, the U.K., Germany, China and Russia, known collectively as the P5+1 — aim to contain the nuclear program and prevent what many warn could be a nuclear weapons crisis. Iran maintains that its aims are peaceful and that its actions fall within the country’s sovereign rights.

Three major sticking points

Three main sticking points remain. Iran wants the Biden administration to remove its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps from its designated terrorist list, which so far Washington seems unwilling to do.

It also wants a guarantee that the deal will be binding regardless of future U.S. administrations. Biden cannot legally guarantee that, and the reality remains that another administration could cancel any deal just as former president Donald Trump did.

The third item is a long-running investigation by the IAEA into traces of uranium found at three of Iran’s undeclared nuclear sites several years ago. Tehran wants it shut down, something the agency itself, as well as Western governments, are opposed to.

The regime appears to have found a winning formula: widening its nuclear footprint while narrowing the inspections and monitoring regime.

Behnam Ben Taleblu

Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense of Democracies

The U.S. didn’t seem to have much patience with Tehran’s demands, with State Department spokesperson Ned Price saying this week that “the only way to achieve a mutual return to compliance with the JCPOA is for Iran to drop further unacceptable demands that go beyond the scope of the JCPOA. We have long called these demands extraneous.”

‘Now or never situation’

In the time since Trump withdrew the U.S. from the deal in May 2018 and reimposed harsh sanctions on Iran, the Islamic Republic’s government has pushed ahead with rapid nuclear development.

Its stockpile of enriched uranium is now at 60% enrichment, its highest ever and a huge leap from the 3.67% limit set out by the 2015 deal, formally called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action or JCPOA.

The level required to be able to make a bomb is 90%. Commercial enrichment for energy use is between 2% and 3%. It’s also slashed IAEA access to its nuclear sites for monitoring.

“The restoration of the deal is getting close to a now or never situation,” Hussein Ibish, a senior fellow at the Arab Gulf States in Washington, told CNBC.

“We have little time to lose and about as plausible a framework for getting back to the 2015 deal as we are ever likely to have. So either it’s going to happen in the near future or it’s going to become increasingly difficult and of increasingly less value, at least regarding containing Iran’s nuclear ambitions.”

Much uncertainty remains – and that’s deliberately part of Iran’s strategy, said Sanam Vakil, deputy head of the Middle East North Africa program at U.K. think tank Chatham House.

“This is the Iranians taking us down to the wire, dangling the prospect of the deal and trying to extract final concessions, guarantees from both the IAEA and the P5+1 … part and parcel of the negotiating strategy,” she said.

“They’re both in a stalemate. And they’re both actually in a position of weakness,” Vakil said, noting the Biden administration’s concern over Iran’s nuclear capability if no deal is reached, its aim of achieving a foreign policy “win” before the November midterm elections, and Iran’s suffering economy desperately in need of sanctions relief.

But, she added, Iran is known for its “strategic patience,” waiting out the other side until they can get the most possible concessions out of them.

No guarantee a deal will last

Meanwhile, Biden faces harsh criticism from political opponents fiercely opposed to any deal with Iran.

“Every quest for a guarantee is just another opportunity Tehran is taking to have Washington fight among itself and attempt to offer more in exchange for less,” said Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

“Under these circumstances, the only reasons Iran might agree to a deal like the JCPOA is to repair its economic armor in advance of another change in U.S. policy after 2024.”

Indeed, many question why a deal that could be ripped up by the next U.S. administration is even worth considering for Iran.

Through this deal Iran would regain access to its foreign reserves, which are estimated to be well over 100 billion, Vakil noted. “That injection of liquidity into the Iranian economy will help in infinite ways from investment to paying government wages to supply chain challenges,” she said. “So even if this deal is a two-year deal, as many see it to be, it’s a two-year reprieve, and it stems a nuclear crisis.”

Tehran’s moves to escalate its nuclear activity have put it in the driver’s seat for these negotiations, Ben Taleblu said. “The regime appears to have found a winning formula: widening its nuclear footprint while narrowing the inspections and monitoring regime.”

Nonetheless, both the U.S. and Iran have an interest in continuing negotiations rather than ditching them altogether, some analysts say, arguing the alternative for both parties is worse.

“Those who have argued that no deal is better than the restored JCPOA have in practice unleashed Iran’s nuclear program and failed to produce a better alternative,” said Ali Vaez, Iran project director at the International Crisis Group.

“Right now, the options are either to restore a deal that would put Iran’s nuclear program in a box, acquiesce to Iran with a bomb or bomb Iran.”