[ad_1]

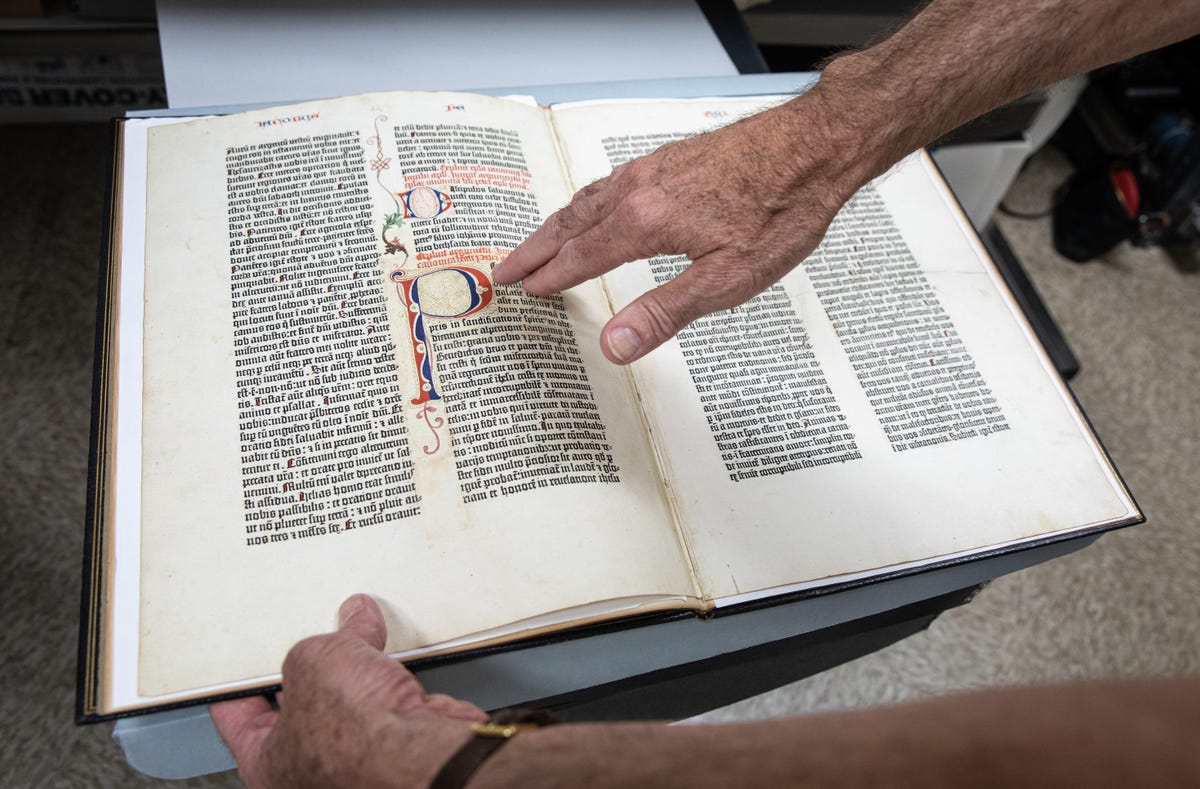

I’m a little nervous. In my right hand, I’m holding a priceless piece of human history. And that’s not hyperbole. It’s a weathered black binder, emblazoned with gold text on the front. In Gothic-style text it reads “A Leaf of The Gutenberg Bible (1450 – 1455).”

Yes, that Gutenberg Bible. These original pages, that date back to the 15th century, have come to the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Northern California to be blasted by a high-powered X-ray. Along with the Bible pages, a 15th-century Korean Confucian text, a page from the Canterbury Tales written in the 14th century and other western and eastern documents are set to endure the barrage. Researchers are hoping that within the pages of these priceless documents lie clues to the evolution of one humankind’s most important inventions: the printing press.

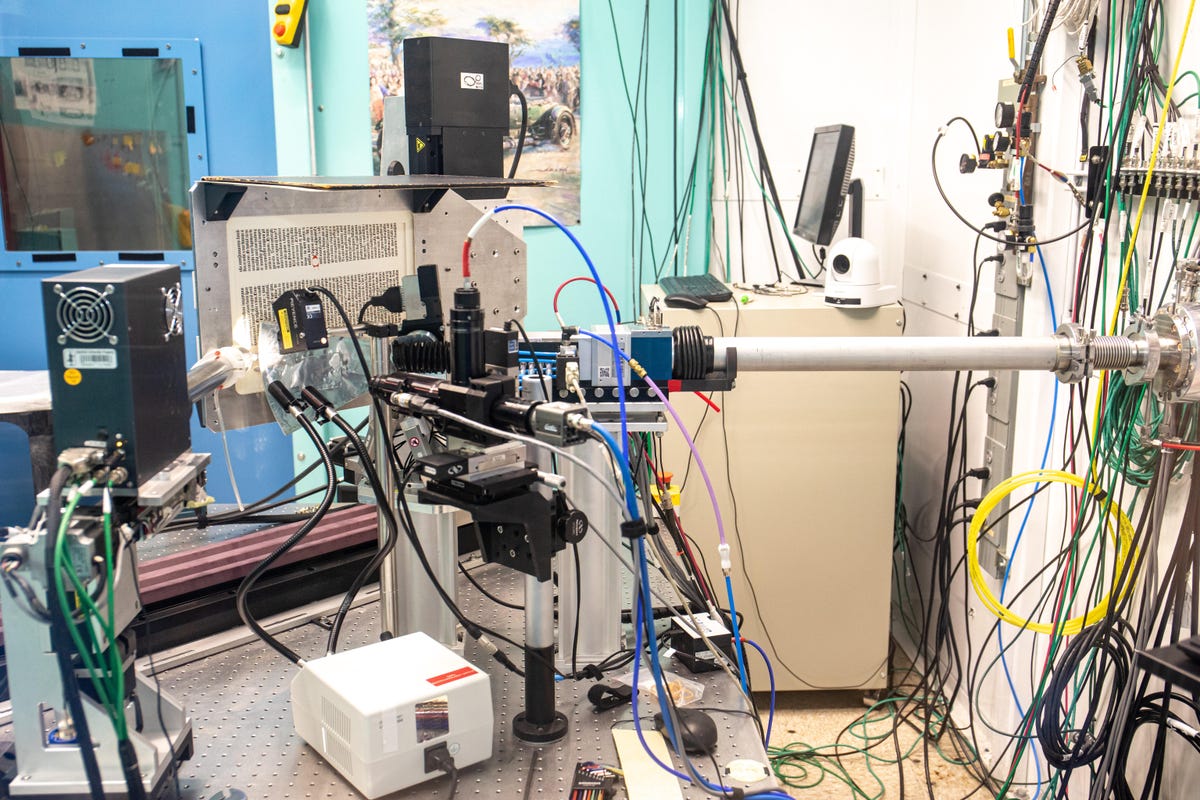

A page from an original Gutenberg Bible (1450-1455 AD) is scanned by a beam from SLAC’s synchrotron particle accelerator.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

“What we’re trying to learn is the elemental composition of the inks, the papers, and perhaps any residues of the typefaces that are used in these Western and Eastern printings,” said imaging consultant Michael Toth.

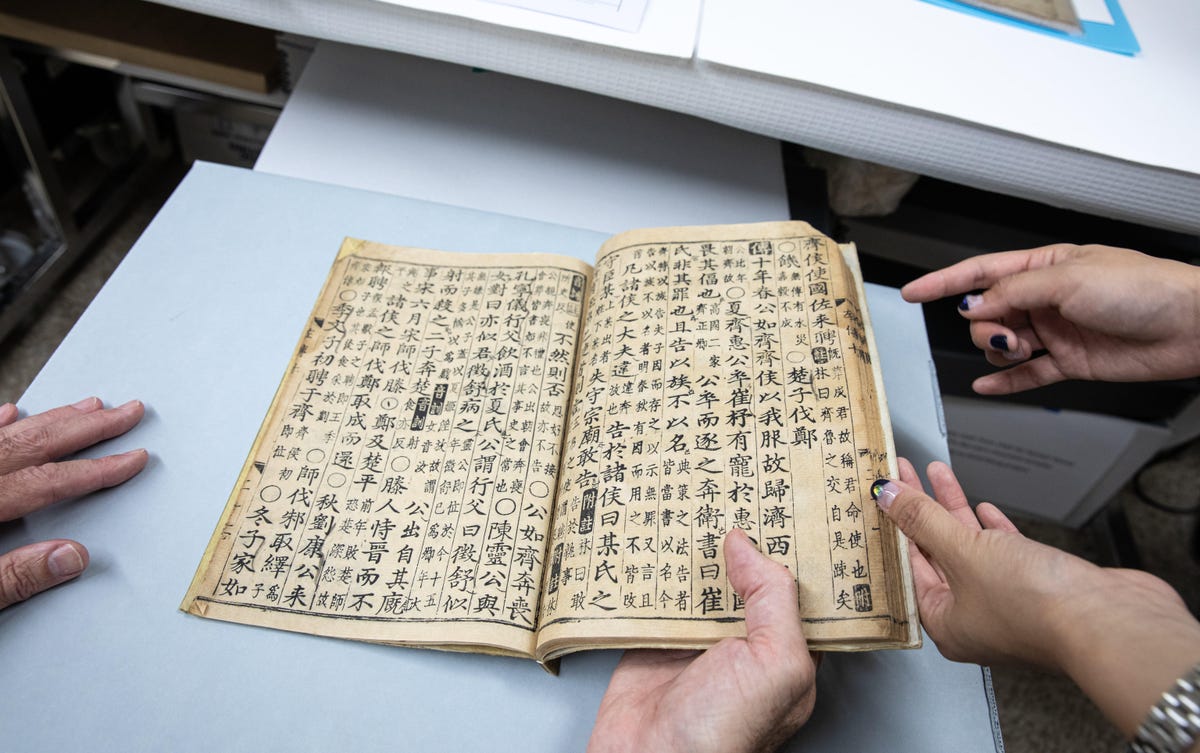

For centuries, it was commonly believed Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press around 1440 AD in Germany. He’s thought to have printed 180 Bibles (fewer than 50 are known to exist today). But more recently, historians have uncovered evidence that Korean Buddhists began printing around 1250 AD.

A page of the Gutenberg Bible from the First and Second Epistles of Peter, mid-15th century.

Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

“What is not known is whether those two inventions were completely separate, or whether there was an information flow,” said Uwe Bergmann, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin. “If there was an information flow, it would have been, of course, from Korea, to the west to Gutenberg.”

To put it more plainly: Was Gutenberg’s invention based, at least in part, on Eastern technology? That’s where the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source comes in.

The Spring and Autumn Annals, Confucius, c. 1442.

Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

A synchrotron is a particle accelerator that fires electrons into a massive ring shaped tunnel in order to generate X-rays (as opposed to SLAC’s more famous linear particle accelerator, the two-mile long LCLS). These X-rays give scientists the ability to study the structural and chemical properties of matter. To see exactly how they’re using SSRL to study the priceless documents, watch the video above.

By firing the SSRL’s thinner-than-a-human-hair X-ray beam at a block of text on a document, researchers can create two-dimensional chemical maps that detail elements present in each pixel. It’s a technique called X-ray fluorescence imaging, or XRF.

The Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

“The atoms in that sample emit light, and we can track which elements that light must have come from on the periodic table,” said Minhal Gardezi, a PhD student working on the project.

Though the SSRL’s X-rays are powerful, they don’t damage the documents, giving scientists a holistic view of the molecules that make up the ancient texts. They also give them the ability to look for trace metals that historians say should not be in the ink. That would indicate they probably came from the printing press themselves. “That would mean we could learn something about the alloys which were used in Korea and by Gutenberg and then maybe later by others,” Bergmann said.

Scientists can use X-rays to create two-dimensional chemical maps of ancient texts like this Confucian document.

Mike Toth/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

If they find similarities in the chemical compositions of the documents, that could contribute to ongoing research into the differences and similarities of the printing technologies, and whether there was an exchange of information from East Asian cultures to the West.

However, every scientist I talked with on the project made it clear that even if similarities between the two documents are found, it wouldn’t definitively prove one technology influenced the other.

The documents are on loan from private collections, the Stanford Library and archives in Korea. The research at SLAC is part of a larger project led by UNESCO called From Jikji to Gutenberg. The findings will be presented at the Library of Congress next April.

[ad_2]