Between 5 billion and 7 billion years from now, our sun will reach the end of its life. Its hydrogen supply — the juice that keeps it going — will fizzle out, and the star that once illuminated everything we know and love about our world will cool, dim and turn into a stellar corpse, or white dwarf.

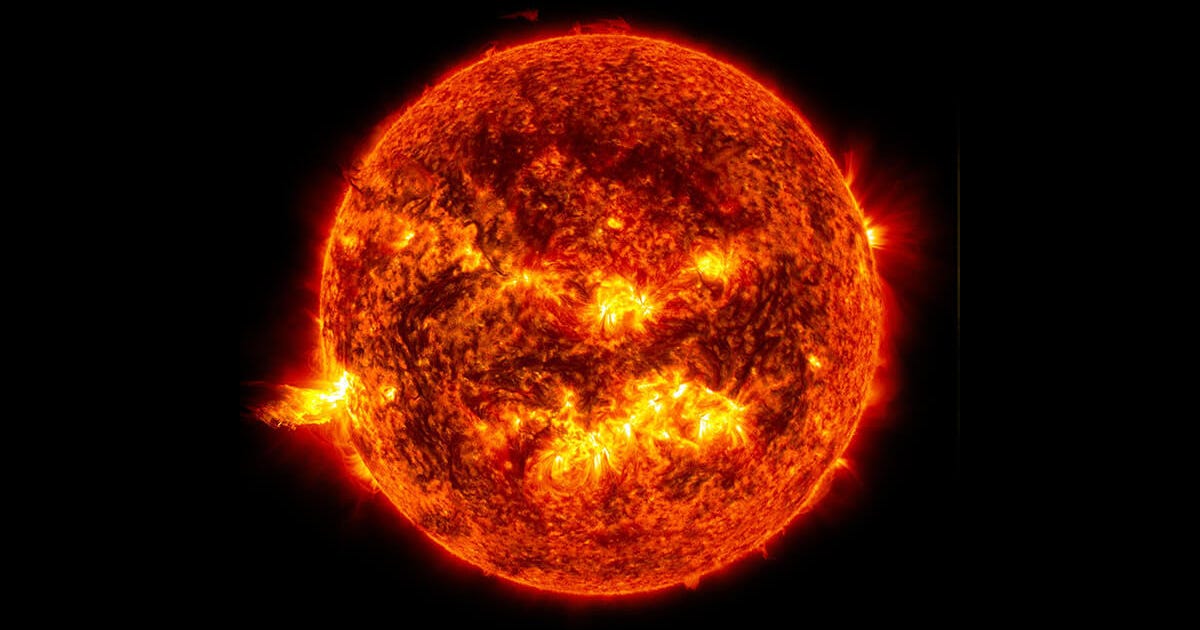

Don’t fret too much, though, because that’s obviously quite far off from now. At present, our sun is considered to be in the prime of its life. It’s in its comfortable middle age, at 4.57 billion years old, productively fusing hydrogen into helium and shining away like a glorious paper lantern.

But scientists are still interested in understanding the sun’s future trajectory.

Though we might expect our host star to be the easiest of its kind to study, it’s actually a lot harder to analyze than stars farther away because it’s so utterly bright due to its proximity. We need special telescopes and instruments tailored to solar observations. Yet, “If we don’t understand our own sun — and there are many things we don’t know about it — how can we expect to understand all of the other stars that make up our wonderful galaxy,” Orlagh Creevey, an astronomer from the Côte d’Azur Observatory in France, said in a press release.

Creevey is also part of the European Space Agency’s massive endeavor to map the entire Milky Way galaxy with unprecedented detail. It’s called Gaia — and sure enough, while building an ultimate diagram of our cosmic neighborhood, Gaia collaborators figured out what will happen to the sun billions of years from now.

In short, the team found that the sun will reach its maximum temperature at approximately 8 billion years of age, after which it’ll cool down but continue to increase in size. At around 10 billion to 11 billion years of age, Gaia data revealed, the sun will become a spectacular red giant (like the 10th-brightest star in the night sky, called Betelgeuse) before beginning its eventual end-of-life sequence.

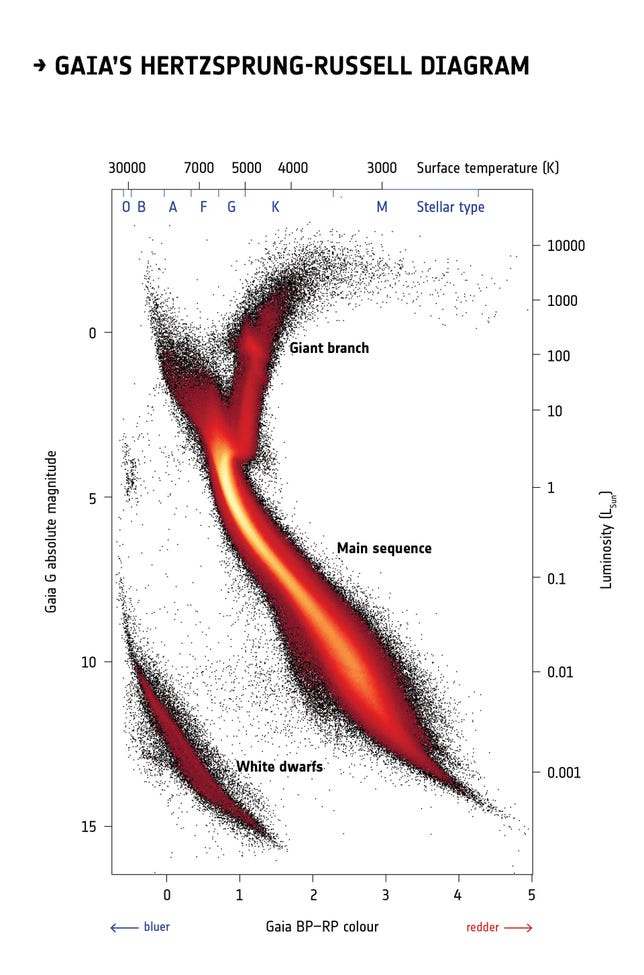

A visual representation of the sun’s lifetime can be seen below. It’s following a line found on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, which plots a star’s intrinsic luminosity against its effective surface temperature. Note how, as the video progresses, the sun’s path begins to escalate. Exponentially.

The evolution of a sunlike star, as derived from ESA’s Gaia mission data release 3, from within the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram.

ESA/Gaia/DPAC

This version of a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram was obtained with a selection of stars from Gaia’s second release catalog. It’s the most detailed to date made by mapping stars over the entire sky, according to ESA.

ESA/Gaia/DPAC

The way the team derived this information was sort of by casting an ultra-wide net across all the Gaia data retrieved of the Milky Way so far, then identifying stars with temperatures, surface gravities, chemical compositions, masses and radii that are similar to those of the sun. For example, the search was concentrated on surface temperatures between 3,000 kelvins and 10,000 kelvins because the sun has a current surface temp of 6,000 kelvins.

But while searching for these candidates, the team made sure to pick out stars similar to our sun yet different in age, so a detailed timeline could be constructed. “We wanted to have a really pure sample of stars with high precision measurements,” Creevey said.

All in all, they found 5,863 ideal solar doppelgangers, according to ESA.

Going forward, according to the Gaia collaboration, not only will this be useful for developing a clear sun trajectory, but it’ll also be useful for scientists who have other solar questions, such as “do all solar analogues have planetary systems similar to ours? Do all solar analogues rotate at a similar rate to our sun?”