On Thursday, the White House declared monkeypox a federal public health emergency, which will increase funding and resources to address the current outbreaks in the US.

The announcement follows similar emergency declarations by California and Illinois and New York state. All three states are home to large gay communities and, to date, men who have sex with men are the largest sector of the population impacted by the outbreak.

There were 7,101 confirmed cases of monkeypox in the US as of Aug. 5, according to data from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and roughly 98% of those are among gay/bisexual men.

Of course, monkeypox is not limited to LGBT people: Most cases in Africa, where the disease is endemic, are not among gay men, the World Health Organization reported.

Transmission can occur via almost any direct skin-to-skin contact with infected lesions, rashes, scabs or fluids. It can also be passed on by touching surfaces, clothing or other objects used by someone with monkeypox.

When WHO declared the disease a global health emergency on July 23, director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus underscored the importance of adopting policies that protected the dignity and civil liberties of affected communities.

He cautioned that “stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus.”

At the same time, Tedros said, because transmission seems concentrated among gay/bi men — especially those with multiple sexual partners — “this is an outbreak that can be stopped with the right strategies in the right groups.”

Here’s what men who have sex with men need to know about monkeypox, including whether it’s a sexually transmitted infection, what safer-sex practices authorities are recommending and how the virus could interact with HIV.

For more information on monkeypox and the LGBTQ community, check out resource pages from GMHC, HRC, WHO and the CDC.

What is monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a virus in the same family as smallpox, though it is milder and rarely fatal. It was first documented in humans in 1970 and is endemic in parts of Central and West Africa, especially the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The first reported cases of monkeypox in the US were in 2003, all linked to infected prairie dogs being kept as pets.

Fatality rates are very low, between 1% and 10% depending on the strain, and deaths usually occur in young children and those with compromised immune systems. As Aug. 5, no deaths have been reported in the US.

Is monkeypox a sexually transmitted infection?

Despite misinformation, including some statements from elected officials, health officials have not designated monkeypox a sexually transmitted infection.

According to WHO, the virus can spread through any close skin-to-skin contact. That includes oral and penetrative sex with someone who has symptoms, but it can also include hugging or using contaminated towels, clothing or bedding.

Framing monkeypox as an STI — and perpetuating the idea that it’s only a threat to gay/bi men — is both stigmatizing and dangerous, according to Dr. Michelle Forcier, a clinician with the LGBTQ-affirming wellness site FOLX Health.

“The monkeypox rumors are harmful because they isolate and seem to ‘blame’ a particular group of persons for spreading this infection,” Forcier told CNET’s sister site Healthline. These rumors “may keep persons exposed or infected from getting medical attention,” she added.

It may also lead individuals to mistakenly think precautions used for STIs will stop monkeypox. Condoms may help prevent transmission, but according to the CDC, “condoms alone are likely not enough to prevent monkeypox.”

How can gay men protect themselves from monkeypox?

Given that the virus can be passed on surfaces, health officials are recommending frequent cleaning of bedding, sex toys and fetish gear.

On July 27, WHO recommended that gay and bisexual men limit their sexual partners during the outbreak, especially while availability of the vaccine is still limited.

“For men who have sex with men, this includes for the moment, reducing your number of sexual partners, reconsidering sex with new partners, and exchanging contact details with any new partners to enable follow up if needed,” Tedros told reporters.

Read more: New Monkeypox Symptoms Are Different From Previous Outbreaks: Here’s What to Look For

The messaging has divided some in the community.

“We know from 40 years of experience with the AIDS epidemic that information that makes people feel ashamed about their sexual behavior doesn’t lead to good public health outcome,” said Jason Cianciotto, vice president of policy and communication at GMHC, a leading LGBTQ health organization in New York.

GMHC began in the early 1980s as a grassroots AIDS organization formed by Larry Kramer and others who felt government officials were failing to act swiftly in the face of a virus targeting gay and bisexual men.

With monkeypox, Cianciotto told CNET, his organization is urging people to take care of themselves and each other.

“That means making smart choices, recognizing someone who might have symptoms and having a conversation with a potential sexual partner,” Cianciotto said.

At the same time, he added, because the vaccine is still so scarce, “people do need to consider the choices they make.”

The CDC website recommends avoiding intimate, skin-to-skin contact if you or the other person have an illness or rash — even if it’s not confirmed to be monkeypox.

The agency suggests virtual sex and masturbation at a distance of at least six feet as alternatives to in-person intimate contact to prevent the spread of the virus.

How is the gay community responding to monkeypox?

Adam Baran hosts a monthly sex party in Brooklyn. Given the spread of the monkeypox virus, he canceled the July gathering.

“I’m hoping, cautiously, that we might be able to have a party in August,” Baran said. “But I’ve definitely had to adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach.”

It’s difficult to know how much precaution to take, said veteran New York nightlife promoter Daniel Nardicio, especially after more than two years of COVID lockdowns and isolation.

Nardicio hasn’t stopped his weekly underwear party on Fire Island, a popular gay beach getaway about two hours outside Manhattan. But he has included information on monkeypox in social media posts and event emails.

A pop-up monkeypox vaccine clinic in Cherry Grove on Fire Island.

James Carbone/Newsday RM via Getty Images)

“With COVID we just stopped everything,” said Nardicio. “With this, we’re monitoring things closely. Beyond that, I don’t think we’re in a position where [we’re] going to have to stop events yet.”

Nardicio is not bothered by WHO’s recommendations for men who have sex with men. “It’s not slut-shaming to tell someone to limit your partners when there’s an outbreak,” he said. “This is a community that is used to jumping into action and taking health crises seriously.”

Baran, Nardicio and Cianciotto all say they’ve seen massive interest in getting vaccinated in the gay community, far outstripping the availability of Jynneos, the two-dose monkeypox vaccine approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

“The desperation for the vaccine and the failure of the government to take care of this is a big topic of conversation,” Baran said. “Almost everyone I know is trying desperately to get vaccinated. In fact, the only people I know who aren’t running to get the shot are monogamous couples who feel like, ‘We’re not the highest risk group — we’re not gonna take someone else’s spot.'”

In mid-July, pop-up monkeypox vaccination sites launched on Fire Island. Nardicio credited Eddie Fraser, vice president for corporate relations with Northwell Health and a Fire Island regular, for helping make it happen.

How can I get the monkeypox vaccine?

Many gay men feel frustrated with the rollout of the monkeypox vaccine, which falls to the federal government, and inadequate access to testing.

It wasn’t until nearly two months after the first cases were reported in New York that some 300,000 doses of a vaccine owned by the US were finally shipped from a warehouse in Denmark.

Even now, with the White House making more than 1.1 million doses of the vaccine available to states and cities, supplies are still relatively limited. Officials told The New York Times that’s partly because the government waited too long to ask Bavarian Nordic, which makes Jynneos, to bottle and fill the vaccine orders already already purchased.

Read more: What You Need to Know about the Monkeypox Vaccine

Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

“Gay sex is not driving this epidemic,” Joseph Osmundson, a gay biophysicist at New York University and author of the new essay collection Virology, said on the podcast In The Bubble. “This epidemic is being driven by a lack of access to resources globally that could prevent spread. People want to get vaccinated and they can’t get vaccinated.”

In New York, the NYC Health portal offers appointments for the handful of vaccine sites around New York. Cianciotto says it took three tries for the city to set up a site that didn’t crash.

“Something like 38,000 people tried to access it in the first hour,” he added.

On Aug. 5, there were no available appointments on the portal for the second Jynneos shot. Some clinics have had to stop offering a second dose of the vaccine to ensure the supply of the first, the Associated Press reported.

“They announce on Twitter when the new batch of appointments will go live and you have, like, 24 hours to schedule one,” Baran said. “So, of course, it gets all filled up right away. It’s like trying to get Beyoncé tickets.”

Read more: The Symptoms, Treatment and History of Monkeypox

There are several community-based organizations like GMHC, that do direct outreach with LGBT health, including the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center and Mount Sinai Hospital. They don’t have the vaccine itself but are given a select number of appointment slots, usually prioritized for sex workers, queer people of color and other individuals in the highest risk categories.

San Francisco has a list of drop-in and appointment vaccination sites on the city government website, though at least one clinic had to close due to lack of supply. The Department of Public Health said it has only received 12,000 of the 35,000 doses it requested from the federal stockpile. (It was told on Aug. 2 it will receive 10,700 more doses in its next allotment.)

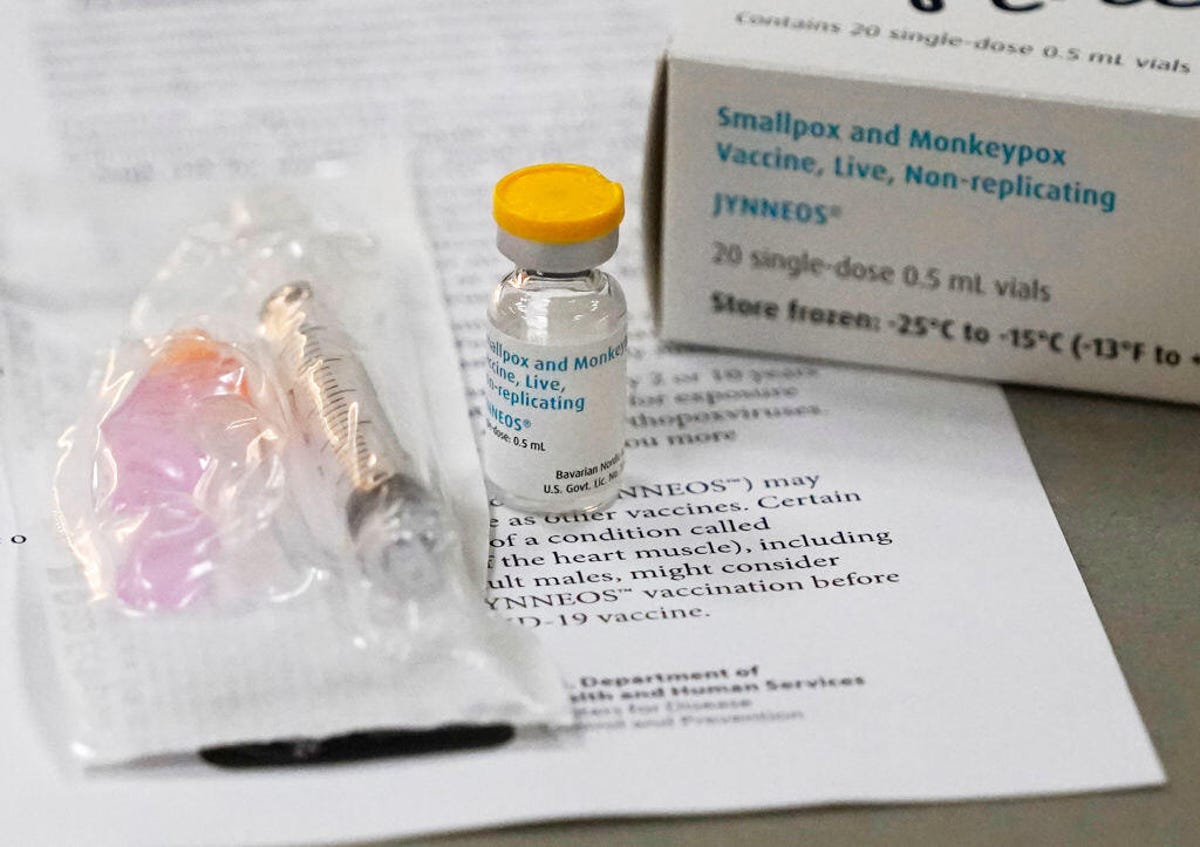

A vial of Jynneos monkeypox vaccine.

David Joles/Star Tribune via Getty Images

Most infections in Illinois, which ranks third in the number of cases after New York and California, have been reported in Chicago. The Chicago Department of Public Health website has a list of vaccination sites and scheduling details.

According to a July 27 CDPH update, vaccine supply remains very limited there, as well, “though it is expected to continue to ramp up over the next few months as the U.S. acquires additional doses.”

But with an estimated 120,000 men who have sex with men in Cook County, CDPH continued, “many more individuals want vaccine than can receive it.”

Cianciotto said it’s helpful that so many gay men are already engaged with health care and know where and how to access information. He acknowledged, though, that doesn’t necessarily ring true for lower-income communities of color, immigrants and trans and gender-nonconforming individuals.

And he’s worried that, as monkeypox spreads to other parts of the US, the response might be more lackluster.

“Will Republican governors even request the vaccine?” he said. “We’re being hit with another virus while my community is faced with what I believe is the most anti-LGBTQ era in US history. I’m concerned how this issue will be used to further the political goals of a minority of elected officials and theocratic nationals who employ fear and anxiety to win elections.”

Are people with HIV more at risk for monkeypox?

People with HIV are considered a priority population for getting vaccinated against the monkeypox virus. In Europe, among the people with monkeypox for whom HIV status was known, 30-50% were HIV-positive.

It’s not clear yet if HIV impacts the risk of being infected by MPX or developing monkeypox after exposure. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, though, people with advanced or untreated HIV may be at higher risk of more severe or prolonged symptoms.

In addition, the rash associated with monkeypox can sometimes lead clinicians to mistake it for shingles, thrush, scabies, herpes or other rash diseases seen in people with HIV.

Those with an inadequately treated viral load (i.e., a T-cell count of less than 350) have shown higher rates of secondary bacterial infections, according to the CDC, as well as a greater likelihood of prolonged infectiousness and a continuous rash rather than discrete lesions.

Tecovirimat (known commercially as TPOXX), has been given to some people with HIV to treat monkeypox.

Yuki Iwamura/AFP via Getty Images

Individuals on effective antiretrovirals, however, haven’t shown higher incidence of hospitalization or death. And the Jynneos vaccine approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent monkeypox has been proven safe and effective in people with HIV.

The effectiveness of ACAM2000, a replicating viral vaccine developed to combat smallpox, has been supported by human clinical trials and animal studies — and ACAM2000 is much more readily available than Jynneos. But it’s not recommended for anyone with HIV, regardless of their viral load.

Antiviral medications, especially tecovirimat (known commercially as TPOXX), have been used to treat some people with monkeypox, though its availability is limited and providers don’t always know about it.

So far there have been few reported negative interactions between tecovirimat and antiretroviral therapies for HIV.

How is the White House responding to the monkeypox outbreak?

The Biden administration declared the monkeypox outbreak a federal public health emergency on Thursday. In addition to increasing resources, that is expected to ease coordination between federal, state and local health officials.

On Aug. 2, Robert Fenton, who helped lead FEMA’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign, was appointed to serve as White House coordinator to combat the spread of monkeypox.

Out physician Demetre Daskalakis, director of HIV/AIDS prevention at the CDC, was named deputy coordinator.

Torrian Baskerville, director of HIV and health equity at the Human Rights Campaign, applauded President Joe Biden for tapping two public health officials with significant experience and expertise.

“The reality, though,” Baskerville said in a statement, “is that we need much more from our government and the window for immediate action is rapidly closing.”

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.