In a 64-33 vote on Wednesday, the Senate finally passed the CHIPS Act, a $52 billion package that aims to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the United States. The House is likely to approve the funding by the end of the week, and President Joe Biden is expected to sign the legislation soon afterward. But while its biggest champions have connected the CHIPS Act to the ongoing chip shortage, the legislation won’t really help, at least in the short term.

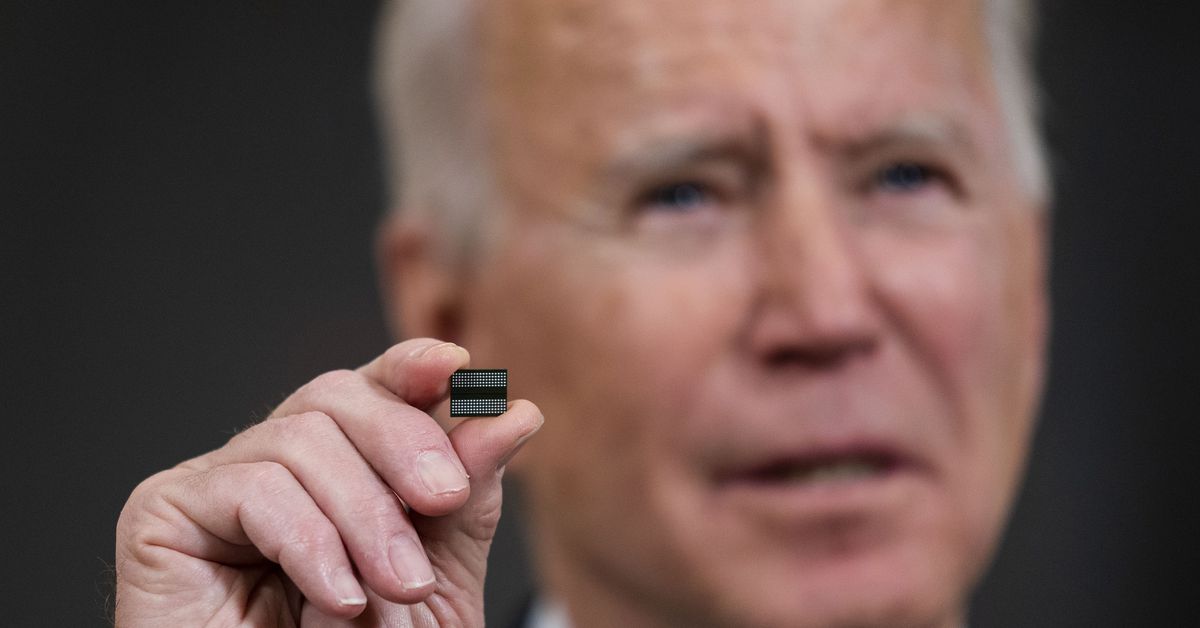

“Semiconductor chips are the building blocks of the modern economy — they power our smartphones and cars,” said President Biden in a tweet before the legislation was formally approved by the Senate. “And for years, manufacturing was sent overseas. For the sake of American jobs and our economy, we must make these at home.”

The bulk of the CHIPS Act is a $39 billion fund that will subsidize companies that expand or build new semiconductor manufacturing facilities in the US. The Commerce Department will determine which companies receive the funding, which will be disbursed over five years. More than $10 billion is allocated to semiconductor research, and there’s also some support for workforce development and collaboration with other countries. The bill also includes an extensive investment tax credit that could be worth an additional $24 billion.

It’s been a long journey for the CHIPS Act, which has been renamed the CHIPS and Science, or CHIPS+, Act: Democrats had originally planned to incorporate support for domestic semiconductor manufacturing within a much broader package that focuses on American competitiveness with China. Sen. Mitch McConnell said Republicans would oppose Democrats’ plans to use reconciliation to pass the bill, and negotiations between the two parties, and across the two chambers, ultimately failed to produce a compromise. The CHIPS+ Act was only approved after Congress separated semiconductor funding from those other measures, and after several chipmakers warned that they might scale back their plans for new factories in the US. Intel even delayed groundbreaking at its chip mega-factory in Columbus, Ohio, which the company could invest more than $100 billion in over the next decade.

On its face, the idea of increasing semiconductor manufacturing in the US seems like it would help address the global supply crunch for computer chips, which has made it harder to buy everything from cars and laptops to sex toys and medical devices during the pandemic. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has even suggested that the funding package could help fight inflation, presumably by making these goods cheaper.

But while it’s certainly fair to call the legislation a victory for bipartisanship, this plan is primarily focused on keeping up with China’s growing investment in its own domestic chip industry — not solving the present issues with the tech supply chain. The chip factories produced by this package won’t be complete for years, and the bulk of the funding won’t necessarily go toward basic chips, also known as legacy chips, which account for much of the ongoing shortage. And that shortage may be nearing its end anyway.

The CHIPS+ Act is about America

America’s supply of advanced chips, which are sometimes defined as chips with transistors that are less than 10 nanometers wide, is the primary motivation for passing the CHIPS+ Act. These chips are extremely difficult to manufacture, and they’re also critical for certain types of technology, including weapons that the US military depends on. Right now, almost all of these chips are made in Taiwan, and none are made in the US. This has US officials worried about the possibility of China trying to invade Taiwan and threaten America’s supply of advanced chips.

“So if, God forbid, China were to — in any way — disrupt our ability to buy these chips from Taiwan, it would really be an absolute crisis in our ability to protect ourselves,” warned Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo this week.

These advanced chips are a far cry from basic chips that perform simple functions, like power management. Basic chips are typically not a major priority for some of the biggest chip companies, since they don’t have a particularly high profit margin. Still, these chips are necessary components for most electronics, so when consumers originally rushed to buy new tech at the height of the pandemic, there weren’t enough basic chips to meet demand. As a result, there were shortages, delays, and price hikes for all sorts of technology, including home appliances and cars.

About $2 billion of the overall package is specifically allocated to basic chips. The bill also includes a provision that would allow companies that accept CHIPS+ Act funding to manufacture legacy chips in China, but not advanced chips.

Regardless, the new factories funded by the CHIPS+ Act likely won’t produce chips until long after the current shortage ends. Chip factories are major industrial plants that usually take years to design and construct before production starts. Semiconductors made at the mega-factory that Intel is planning in Ohio — which will focus on advanced chips — may not end up in consumer devices until 2026, though the company’s CEO has said the shortage might end sometime in 2024. Other experts have said the shortage will end sooner, possibly by next year.

There are already signs that chip demand is slowing down. While there was a surge in demand for electronics during the first two years of the pandemic, inflation-wary consumers are scaling back their purchases. Some chip manufacturers have said that their sales are starting to wane. Device makers are reportedly cutting back on orders from the world’s biggest chip manufacturer, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, and South Korea’s national chip stockpile had its largest jump since 2018 this past June.

Still, US politicians think they’re making a long-term bet on American chip manufacturing. It’s not the first time, as the government funded some of the first semiconductor companies in the mid-20th century. In more recent decades, however, federal support for the American chip industry has declined, while other countries, including China and Japan, have invested heavily in their domestic manufacturing capabilities. Just 12 percent of the world’s chips are made in the US today, compared to about 37 percent in 1990, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association, a US semiconductor trade group that lobbied for the CHIPS+ Act.

Not everyone thinks reversing this trend is worth $76 billion. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has called the legislation a “bribe” and has argued that chip companies are, in effect, extorting American taxpayers. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) said the CHIPS+ Act amounts to “corporate welfare” and suggested imposing tariffs on imported tech instead. Some Republicans, including Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), said the legislation was too soft on China, and officials from China’s US embassy encouraged some business executives to oppose the legislation, according to a Reuters report.

There’s good reason to believe that the CHIPS+ Act won’t be enough to spur a long-term chip renaissance in the US. Other countries, including China, South Korea, and the member states of the European Union, are also ramping up chip manufacturing and investing tens of billions of dollars in the industry.

“This is a very, very good first step,” John Neuffer, the CEO of the Semiconductor Industry Association, told Recode. “But as long as the rest of the world has the subsidy programs in place, we need some kind of incentives to get close to what those subsidies are.”

It’s not clear that there’s political will to give the chip industry even more money, though. After all, it took months for US political leadership to cobble together the CHIPS+ Act incentive package, and they may not be able to do so again. In that sense, it might be fairest to say that with this latest legislation, America is simply catching up.