Does anybody remember GLASS-z13? No?

It was spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope and championed as the “oldest galaxy ever seen” and it was announced… six days ago.

Yes, that’s right. Not even a week ago, two pre-print papers posted to scientific article repository arXiv (pronounced “archive”) detailed some of the earliest analysis of images snapped by the JWST, humanity’s next-generation infrared eye on the cosmos. Lurking within the data were two galaxies — potentially the most distant galaxies humans had ever laid eyes on. One of them was dubbed GLASSz-13 or GL-z13 for short (The Atlantic gave it the cutesy name of “Glassy”).

“JWST has found the oldest galaxy we have ever seen in the universe” one headline read. The story exploded across the web, with Twitter buzzing about it and mainstream outlets picking up on the record-breaking find. It even got its own Wikipedia page!

In the rush of reporting, a few key points were missed. It’s not the “oldest galaxy” we’ve ever seen. It’s maybe the oldest light we’ve ever detected but it’s probably a very young galaxy, no more than a 100 billion years into its life (an important distinction). It’s also important to note GL-z13 is currently just a “candidate” that requires further investigation — the data is pretty good, according to astronomers I’ve spoken with — but further observations would help tick it off as the record holder.

But all that might not even matter.

Hubble and James Webb Space Telescope Images Compared: See the Difference

In a slew of new papers dropped on arXiv Monday, astronomers have picked out galaxies that may lie even further away than GL-z13. It’s a showcase of the power of the revolutionary James Webb Space Telescope.

As soon as researchers were given access to Webb’s first batch of data, they began scouring it for distant galaxies. Webb is the best at finding these galaxies because it sees the cosmos in infrared light, rather than visible light, like the Hubble Space Telescope does.

Visible light from the very earliest galaxies in the universe has been “redshifted.” Because the universe has been expanding since the Big Bang, wavelengths of light get stretched out. When you stretch the light we can see with our eyes, that stretching shifts it toward a redder wavelength. In this case, infrared. Webb is designed specifically to capture this light.

Astronomers denote redshift with z. Higher z values essentially represent a further look back in time. For instance, z = 1 corresponds to around 7.7 billion years ago, whereas z = 10 corresponds to around 13.2 billion years ago.

In the papers uploaded to arXiv, at least three have presented candidate galaxies with a z value greater than 16. This would correspond to around 13.6 billion years ago. One presents a case for a galaxy at z = 16.7, which would correspond to about 250 million years after the Big Bang.

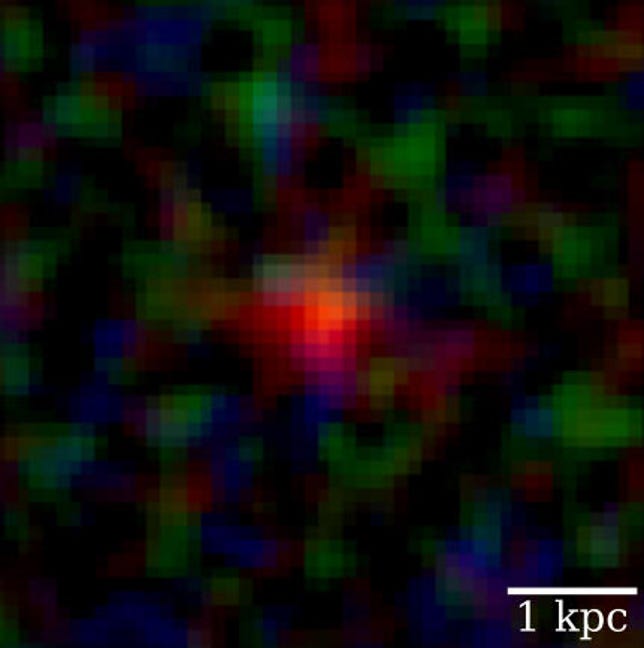

This pixelated red dot could be a galaxy that existed just a few 100 million years after the Big Bang. The scale bar is 1 kiloparsec (about 3,260 light-years).

Finkelstein et al. (2022)/NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI

Another, summarized by astrophysicist Steve Finklestein in this Twitter thread, presents a galaxy at z > 14. Finkelstein named it Maisie’s Galaxy, after his daughter.

The discoveries have astronomers on Twitter buzzing yet again, but where does this leave GL-z13?

Well its z value is about 13 (as the name might suggest), so perhaps it’s Game Over for Glassy.

However, it’s still got a shot at becoming the most distant galaxy ever observed because astrophysicists need to validate what they’re seeing in the JWST data.

“Many of the candidates in these papers aren’t as convincing [as GL-z13],” said Michael Brown, an astrophysicist at Monash University in Melbourne.

There’s even more uncertainty about distances when you bring in the gentle disagreement between astrophysicists about how fast the universe is expanding. We won’t get into that here. In short, confirmation of these galaxies as bonafide galaxies will require further observations which are very likely to come during the first years of Webb’s operation.

And yes, the Webb Space Telescope is poised to deliver even more candidates for the most distant galaxy ever observed beyond today. They might even drop on arXiv tomorrow! While many of these candidates will soon fade from the public consciousness, each will provide a stepping stone for astrophysicists to piece together the earliest moments of our universe. Some of the questions these galaxies will answer haven’t even been asked yet.

In fact, astrophysicists are already finding the early universe might be a lot more busy than they expected. Stars may have started forming at a much faster rate than some models have predicted. How did matter coalesce and start to form these galaxies early on? We don’t know yet. But Webb is, seemingly, already rewriting what we thought we knew about the beginning of, well, everything.

It’s an astronomical revolution. So strap in. It’s going to be one hell of a ride.