But the historic match symbolized the tension Ashe faced throughout his career; the weight of expectation from the tennis world, the racism he faced as a Black athlete and his humanitarian work.

“I think I can almost withstand just about anything. As an African-American athlete, I have experienced racism as a tennis player, going way back,” Ashe says in an interview in the documentary. “I have played extraordinary matches under unbelievable circumstances, but Wimbledon tied my whole life together.”

“To think that he (Ashe) could perform on the tennis court the way he did, and then choose to be an activist the way he was in ways that a lot of Black players would not have been comfortable doing given the time … he was just very different,” Washington tells CNN Sport.

‘There just weren’t a lot of Black players’

“It was wonderful to be compared to him, but considering I turned pro in 1989 and, you know, he was winning grand slams in the 1960s and 70s, it just shows you the glaring, obvious fact that there just weren’t a lot of Black players out there since he last won his last major,” he says.

Like Washington, Ashe started playing tennis at an early age.

As his tennis skills improved, Ashe needed to take a step up in the quality of the opponents he faced. However, his opportunities were stunted by segregation. For example, he was often shunned by the neighboring Byrd Park youth tournament because the public tennis courts were “Whites only.”

‘All brawn and no brains’

As Ashe garnered status in the tennis world, his reluctance to speak out on social issues affecting Black communities in the US caused friction between himself and members of the civil rights movement.

“All around me, I saw these athletes stepping out in front trying to demand civil rights. But I was still with mixed emotions,” Ashe says in an interview in the film. “There really were times when I felt that maybe I was a coward for not doing certain things, by not joining this protest or whatever.”

In his early career, Ashe toed the line between remaining politically neutral to pacify his White colleagues and publicly condemning the racism faced by Black athletes.

“I sense confusion in what an athlete should be, especially in an African-American context. There does still persist in the world myths about Black athletes because we tend to do disproportionately well in athletics,” Ashe adds. “Some people think we are all brawn and no brains. And I like to fight the myth.”

Speaking about Ashe’s observation, Washington says, “That myth has continued on, racism has continued on, discrimination has continued on.

“I can absolutely see how Arthur would have that feeling. And the ironic thing is he was the most intellectual person out on the tour at the time.”

A turning point

In 1968, after Ashe graduated from UCLA and served in the US Army, the American political landscape was upended.

Two figureheads of the African American equality movement — civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and politician Robert F. Kennedy — were assassinated two months apart.

Speaking about King’s assassination, Ashe said: “I was very angry. I also felt slightly helpless. Things would be different now because, I mean, he was sort of seen as our knight in shining armor.

“Being a Black American, I felt a sense of urgency that I want to do something, but I didn’t know what it was.”

Ashe’s speech signaled a turning point in his tennis career. Instead of his platform preventing him from taking a stance on political issues, he began to use it as a vehicle for social change.

‘Calm and confident resolve’

“A lot of people were against him going, but he went anyway, which just shows you, you know, the power of doing what’s right. The power of saying, following your conscience and just doing the right thing,” Washington says.

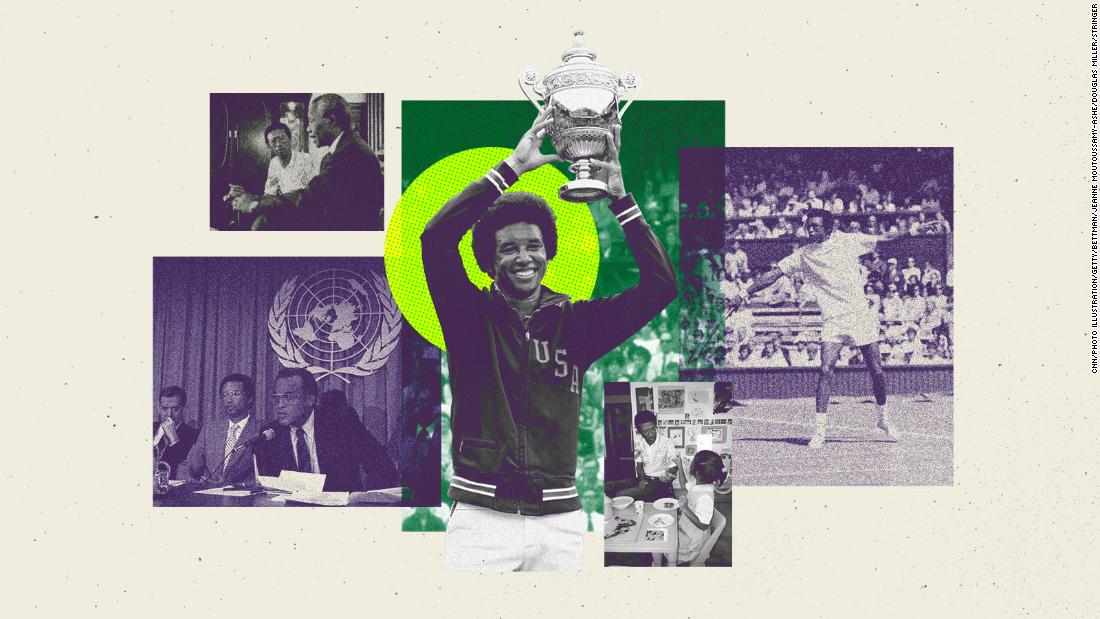

He married photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe in 1977, and in December 1986, his daughter Camera was born.

After his retirement from competitive tennis in 1980 and his subsequent five-year captaincy of the United States Davis Cup team, Ashe forged a blueprint for athlete activism.

He had the ability to facilitate nuanced discussions between opposing sides of the political spectrum, a skill that Washington says was “a very special gift.”

“His demeanor kind of reminds me of Nelson Mandela,” Washington adds. “That is why that’s one of the reasons why he was able to kind of do the things he was able to do, accomplish the things he was able to accomplish.

“It’s very powerful when you have a very calm and confident resolve.”

“Arthur would go in, and he would make statements that when you brushed away the gentility, the niceness, the intelligence, the calmness, his statement would be more militant than mine,” Edwards, the civil rights activist and sociology professor, says in an interview in the documentary.

“To this day, we have not found another person who could speak to both sides of the barricades, and that bridge became so critically and crucially important,” Edwards adds.

Inspiring a generation of athletes

“What I don’t want is to be thought of, when all is said and done, as… or remembered as a great tennis player. I mean, that’s no contribution to make to society,” Ashe says in an interview in the documentary.

Washington says Ashe “created the kind of roadmap” for modern athlete activism.

“Not everyone can be an Arthur Ashe. Not everyone can be a Nelson Mandela… these are giants in the activism world,” Washington says. “I don’t think there’s ever been a tennis player who was as active and as vocal as he has been.”